Instead of Painkillers, Some Doctors Are Prescribing Virtual Reality

Virtual reality therapy may be medicine’s newest frontier, as VR devices become better and cheaper

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/bf/07bf03ec-250d-4166-b9d1-5874c0f61597/waterfriendly2.jpg)

When I reach Hunter Hoffman, director of the Virtual Reality Research Center at the University of Washington, he’s in Galveston, Texas, visiting Shriners Hospital for Children. Shriners is one of the most highly regarded pediatric burn centers in America. They treat children from around the country suffering from some of the most horrific burns possible—burns on 70 percent of their bodies, burns covering their faces. Burn recovery is notoriously painful, necessitating torturous daily removal of dead skin.

“Their pain levels are just astronomically high despite the use of strong pain medications,” Hoffman says.

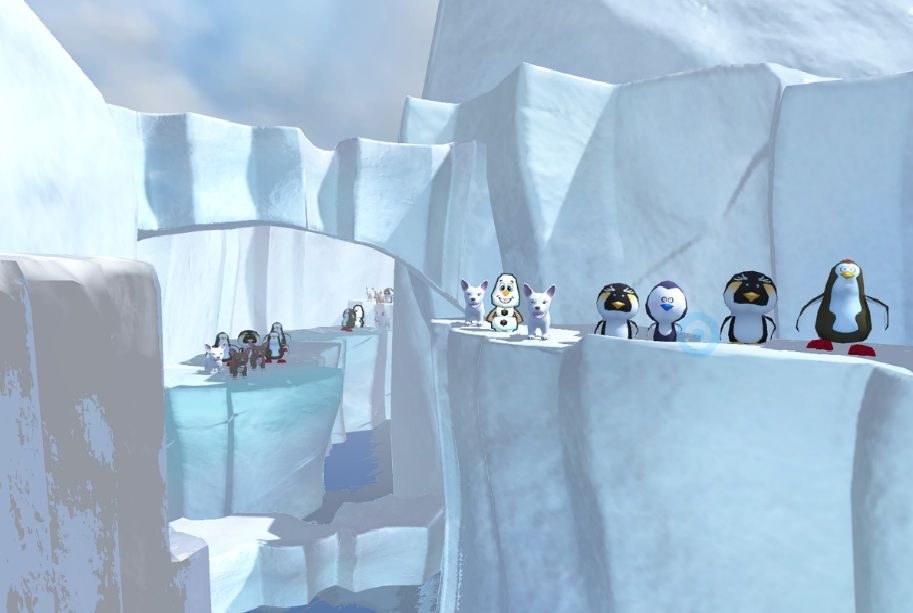

Hoffman, a cognitive psychologist, is here to offer the children a different kind of pain relief: virtual reality. Using a special pair of virtual reality goggles held near the children’s faces with a robotic arm (head burns make traditional virtual reality headsets unfeasible), the children enter a magic world designed by Hoffman and his collaborator David Patterson. In “SnowCanyon,” the children float through a snowy canyon filled with snowmen, igloos and woolly mammoths. They throw snowballs at targets as they float along, Paul Simon music playing in the background. They’re so distracted, they pay far less attention to what’s happening in the real world: nurses cleaning their wounds.

“The logic behind how it works is that humans have a limited amount of attention available and pain requires a lot of attention,” Hoffman says. “So there’s less room for the brain to process the pain signals.”

Virtual reality reduces pain levels up to 50 percent, Hoffman says, as good or better than many conventional painkillers.

The idea of using virtual reality (VR) to distract patients from pain is gaining traction in the medical community. And as it turns out, that’s only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the emerging field of virtual reality medicine.

Perhaps the most established use of virtual reality medicine is in psychiatry, where it’s been used for treating phobias, PTSD and other psychological issues for at least 20 years. A patient with a fear of flying might sit in a chair (or even a mock airplane seat) while inside a VR headset they’re experiencing a simulation of takeoff, cruising and landing, complete with engine noises and flight attendant chatter. This kind of treatment is a subset of the more traditional exposure therapy, where patients are slowly exposed to the object of their phobia until they stop having a fear reaction. Traditional exposure therapy is easier to do when the phobia is of something common and easily accessible. A person afraid of dogs can visit a neighbor’s dog. An agoraphobic can slowly venture outside for short periods of time. But treating phobias like fear of flying or fear of sharks with traditional exposure therapy may be expensive or impractical in real life. That’s where VR has a major advantage. Treating PTSD with VR works similarly, exposing patients to a simulation of a feared situation (a battle in Iraq, for example), and appears to be just as effective.

Hoffman and his collaborators have done pioneering work in using VR for phobias and PTSD. Back in the late 1990s, they designed a program to deal with spider phobia, having a test patient see increasingly close and graphic images of a spider, eventually while also touching a spider toy. The patient was so spider phobic she rarely left the house during the day and taped her doors shut at night. By the end of her VR treatment she comfortably held a live tarantula in her bare hands. Hoffman has also created programs for dealing with PTSD, notably a September 11 simulation for victims of the attacks.

Scientists are quickly learning that VR has many other psychiatric applications. Studies suggest that VR exposure can help patients with paranoia, a common symptom of various psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia. In a recent study published in the British Journal of Psychiatry, patients with “persecutory delusions” were put in virtual reality simulations of fearful social situations. Compared to traditional exposure therapy, the VR-treated patients showed a larger decrease in delusions and paranoia. Other studies suggest VR is helpful for children with autism and in patients with brain damage-related memory impairment. Some of Hoffman’s current research deals with patients with borderline personality disorder, an infamously hard-to-treat illness involving unstable moods and a difficulty in maintaining relationships. For these patients, Hoffman has designed a program using virtual reality to enhance mindfulness, which is known to decrease levels of anxiety and distress.

VR has also been shown to be a boon to amputees suffering phantom limb pain—the sensation that the removed limb is still there, and hurting. Phantom limb pain sufferers typically use “mirror therapy” to relieve their distress. This involves putting their remaining limb in a mirrored box that makes it look like they have two arms or legs again. For reasons not entirely clear, seeing the amputated limb appear healthy and mobile seems to diminish pain and cramping sensations. But this type of therapy has limitations, especially for patients missing both legs or both arms. A recent case study in Frontiers in Neuroscience discussed an amputee with phantom cramping in his missing arm that was resistant to mirror treatment and was so painful it woke him up at night. The patient was treated with a VR program that used the myoelectric activity of his arm stump to move a virtual arm. After 10 weeks of treatment, he began to experience pain-free periods for the first time in decades.

VR also stands to revolutionize the field of imaging. Instead of looking at an MRI or CT scan image, doctors are now beginning to use VR to interact with 3D images of body parts and systems. In one Stanford trial, doctors used VR imaging to evaluate infants born with a condition called pulmonary atresia, a heart defect that blocks blood from flowing from babies’ hearts to their lungs. Before lifesaving surgery can be performed, doctors must map the babies’ tiny blood vessels, a difficult task since every person is slightly different. Using a technology from the VR company EchoPixel, the doctors used a special 3D stereoscopic system, where they could inspect and manipulate holograms of the babies’ anatomy. They concluded that the VR system was just as accurate as using traditional forms of imaging, but was faster to interpret, potentially saving valuable time.

Medical students, dental students and trainee surgeons are also using VR to get a better understanding of anatomy without having to make a single real cut.

As virtual reality devices become higher quality and more affordable—in the past, medical virtual reality devices cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, while an Oculus Rift headset is just over $700—their use in medicine will likely become more widespread.

“There’s really a growing interest right now,” Hoffman says. “There’s basically a revolution in virtual reality being used in the public sector. We’ve been using these expensive, basically military virtual reality systems that were designed for training pilots and now, with cell phones, there are a number of companies that have figured out how to get them to work as displays for VR goggles, so the VR system has just dropped to like 1/30th of the cost it used to be.”

So next time you go to the doctor with a migraine or back pain or a twisted ankle, perhaps, instead of being prescribed a painkiller, you’ll be offered a session inside a virtual reality headset.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)