It Was Only a Matter of Time: Drones Get Their Own Film Festival

Hoping to clean up the tarnished image of drones, a filmmaker shifts the focus to their potential for changing how movies are made

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/04/bb/04bb0b09-3cd7-4473-93c7-50c33bfc45a9/fallout.jpg)

Randy Slavin was tired of drones getting a bad rap. It was time to fight the stigma that they were either covert killing machines or expensive toys of Peeping Toms. As a filmmaker, Slavin knew what drones made possible.

So he organized a film festival.

Slavin gave it an impressive name—the 1st Annual New York City Drone Film Festival. He admits that he wasn’t sure what to expect. Moviemaking with drones isn’t new—the opening rooftop chase scene in the James Bond film “Skyfall” is one celebrated example shot overseas. But it was only last fall that the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) finally allowed a handful of movie companies to use drones for filming in the United States.

So Slavin kept the rules simple. Entries couldn’t be longer than five minutes and at least 50 percent of the video had to have been shot with a camera on a drone. More than 150 videos were submitted, but as Slavin suspected, a lot of them came from people who were still getting the hang of filming from a drone. When the festival opened in Manhattan last weekend, only 35 movies had qualified for judging. They reflected a pretty wide range of drone camera potential—from a music video for the group OK Go to an eerie fly-through of a Ukranian town abandoned after the Chernobyl power plant disaster almost 30 years ago.

Drone on

While drone films like the ones mentioned above are still in short supply, it’s clear to Slavin and others experimenting with this kind of aerial cinematography how much drones could change moviemaking, particularly for documentaries. For starters, drones will be able to go places and capture images that otherwise would require helicopters costing thousands of dollars a day.

“Drones literally go to places people couldn’t get to,” Slavin told Wired. “I have a small drone that fits in a backpack. I can take it on my back, travel wherever I want and get amazing footage.”

He cited a now much-viewed drone video of an erupting volcano in Iceland, footage possible only with an unmanned aircraft.

Drones have other filming advantages over helicopters. They are, in essence, small flying cameras, able to come in tight on a subject without any anxiety about whirling propeller blades. And they can operate in a cinematic sweet spot, lower than a helicopter, but higher than a crane.

That said, they still have their challenges. There can be problems with image quality, and it takes a lot of practice to keep the camera steady. That’s why budding aerial filmmakers have to first become good drone pilots. Plus, the batteries don’t last all that long—minutes rather than hours—meaning that long shoots aren’t yet an option.

Playing by the rules

Then there are the government’s rules. While film companies saw the new exemptions granted by the FAA as a big step forward, the agency is proceeding cautiously when it comes to where and how moviemaking drones can operate. The unmanned aircraft need to always be visible to the human pilot, who holds a private pilot certificate. The film companies also agreed that drones would be used only on closed sets and that they would fly no faster than 57 miles per hour and no higher than 400 feet off the ground. Plus, no filming will be done at night.

But it’s a start, and people like Slavin figure it won’t be that long before drone shots are standard fare in both documentaries and feature films. Already, they’ve spawned an idiosyncratic effect where a shot starts close up on a person, then zooms out high into the sky.

It even has a name. It’s called a dronie.

Here are some of the winners of last weekend’s Drone Film Festival, plus a few others that wowed the audience.

Best in Show: "Superman with a GoPro," by Corridor Digital

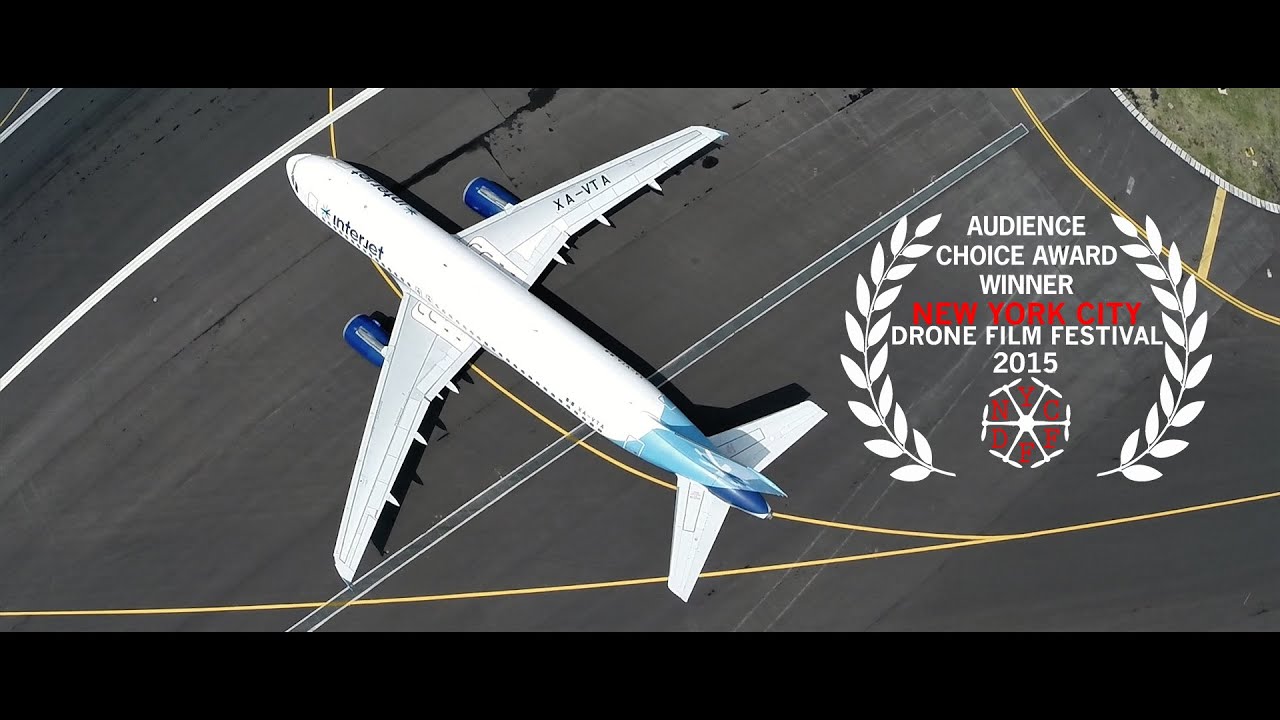

Audience Choice: "Mexico City International Airport From Above," by Tarsicio Sanudo Suárez

X-Factor Award: "I Won't Let You Down," by OK Go

Architecture Winner: "The Fallout," by Jeff Brink and Brian Streem

This one-of-a kind tour of the Mont Saint-Michel monastery off the coast of Normandy in France didn't win, but the film, by Freeway Prod, provides a glimpse of the potential of drones for documentaries.

And finally, here's the winner for best "Dronie," titled "Floating." It's the work of Florian Fisher and Michael Kugler.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)