The Young Inventor Who Is a “Minder” of a Business of Her Own

At age 11, Lilianna Zyszkowski designed a new life-saving device to help people track their medication. That was just the beginning

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/3c/873cca0b-2801-4c6e-965f-894ff64895ab/dec2015_e02_youth-web-resize-v3.jpg)

If you were to look into the personal histories of the world’s great inventors, you would likely find that at some point they came up with innovations that were more pedestrian than the ones that made them famous. For example, booby traps to keep their siblings out of their personal space. “One of them involved dental floss, because it was so small and strong, but you don’t see it,” Lilianna Zyszkowski recalls of one of her own early creations. She blushes slightly. “A lot of things I did back then—I would say they weren’t very beneficial to the world.”

Sitting at a café in the bucolic Berkshire Mountains, Zyszkowski straightens her spine and composes her hands in front of her coffee in a way that makes clear that now, at the wizened age of 15, she is well past these juvenile antics. These days she is, in her own phrase, “famous-ish” for putting her talents to better use, by designing inventions that do help people. Her best known is the PillMinder, a device that tracks medication intake. Zyszkowski came up with the idea in the sixth grade, after her grandfather accidentally overdosed on his blood thinners and ended up in the hospital. “It was pretty scary,” she says.

Zyszkowski was not going to sit around fretting. “I’m like, OK, how can we fix this?” she says. “That’s my mentality.”

Her research suggested that the touch sensors found in common TV remote controls—capacitive chips that react to pressure—would also be useful conductors, and they were cheap and plentiful online. She ordered a batch and, with the help of videos she found online, figured out how to solder them to the bottom of plastic S-M-T-W-T-F-S pill-storage boxes she’d bought at a drugstore. Using copper wires, she connected the chips to a microcontroller, which she programmed (after reading about coding) to notify a private Twitter account whenever a person’s finger touched the sensors. Twitter sent an alert to the user’s smartphone, creating a record of pills taken.

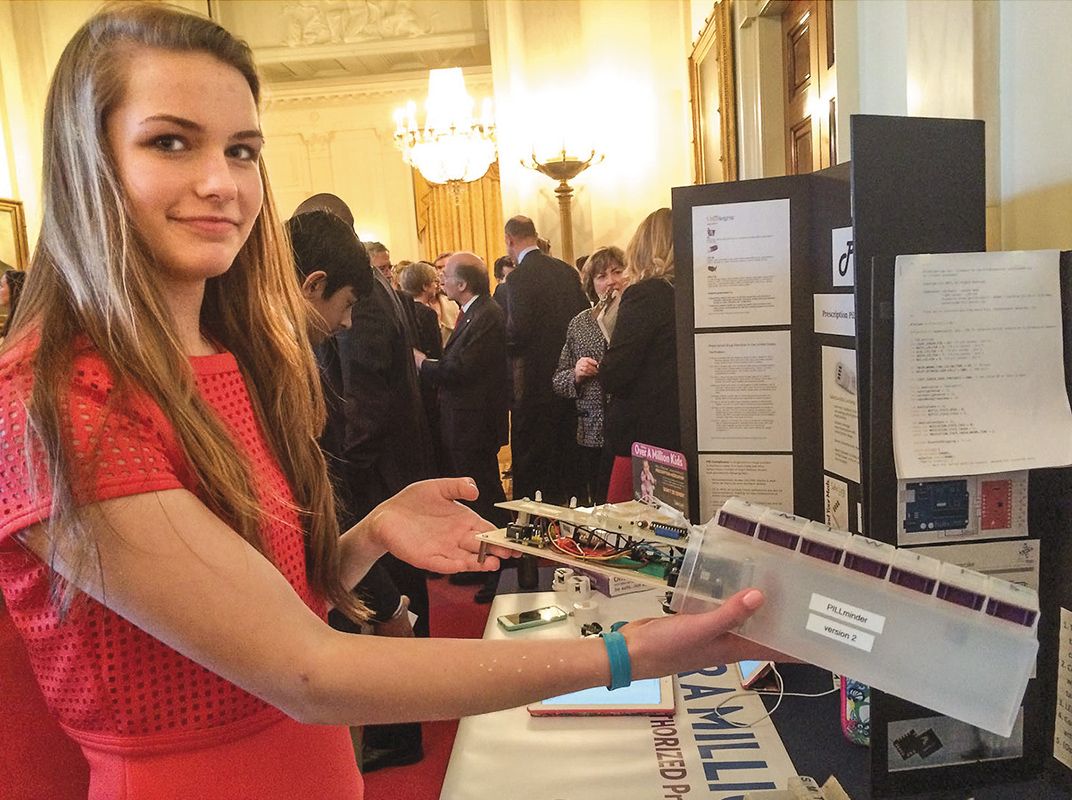

The PillMinder was a hit at the annual kids’ science fair in her area, the Connecticut Invention Convention, where Zyszkowski took home multiple prizes. Soon after, she began working with California-based Gatekeeper Innovation to add PillMinder technology to its Safer Lock combination-based pill-bottle cap. This past spring, Zyszkowski presented the device at the White House Science Fair. “There’s Obama, and there’s me, the only girl in the background,” she says, showing me a picture in which she stands out from a crowd thick with guys in glasses.

Although her business cards describe her as an “inventor,” Zyszkowski doesn’t want to paint herself with just that brush. “My big-vision thing is the Internet of Things,” she says. “Having you and the things you do talk to devices, and having the devices know what to do with that information and connect to everything else and help you—I am really into that.” She admires Elon Musk, whose interest in technological advancement spans multiple industries and applications. “I like people with big ideas,” she says.

**********

A shingle for “Minder Industries” hangs outside the door of the Zyszkowski family office, although the business is not yet incorporated. Running a company at this point in her life would be “too distracting,” Zyszkowski says, climbing the stairs to the building, which is housed on a large estate where, on the day that I visit, stonemasons are laying a terrace overlooking a deep green valley. The sprawling property does not belong to her family but to a business associate of Zyszkowski’s father: Larry Rosenthal.

“Another ‘minder’ looking out for people,” Zyszkowski observes.

Inside, a 3-D printer whirs incongruously in a space that, with its wood paneling and dormant Jacuzzi, gives off a ski chalet vibe. At a desk near the door, Alek, Zyszkowski’s 12-year-old brother and her early muse, stares into his laptop. Alek is an inventor, too—in fact, he tried to enter a device in the same science fair in which his sister debuted the PillMinder. “It was called the Foul Air Response Trigger,” says Lilianna, whose desk is opposite her brother’s. “So, if you figure out the initials for that, you will know what kind of sensor it was—it would sense methane gas and then it would trigger a fan.” The Catholic school they were attending at the time refused to enter it, on the grounds that the name was offensive.

Alek shrugs. “It was funny, though,” he says.

In the center of the office, flanked by his children, sits their father, Edward Zyszkowski, a physicist, developer and venture capitalist. A veteran of Thinking Machines, the pioneering supercomputer firm, Ed Zyszkowski was part of the team that, in the 1980s and ’90s, developed the subfield of computing we now know as “data mining.”

Coming up the stairs with a sandwich for Alek is the children’s mother, Lori Fena, an early Internet activist and intellectual powerhouse in her own right. Fena was the director of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an advocacy group, and the co-author in 2000 of the prescient book The Hundredth Window: Protecting Your Privacy and Security in the Age of the Internet. When the couple started dating in the 1990s, it caused a frisson of gossip among the digerati. A 1997 People magazine interview with Fena about Internet privacy mentioned her then-boyfriend’s job mining people’s data, and Salon.com speculated about the couple’s “spirited debates at the dinner table.” After they got married, they left Silicon Valley and settled in New Marlborough, a quirky town in western Massachusetts, a choice based in part on data mining. “Ed wrote a ‘spider,’” Fena explains—an algorithm into which he plugged 107 criteria, including acreage, proximity to water and the airport, and the quality of local schools.

Over the years, Fena and Zyszkowski have collaborated on several business and nonprofit ventures, including Public Safety Guardian, a device that seeks to improve upon the body cameras worn by police by collecting and storing real-time video footage to protect against tampering.

The family office has served as something of an incubator for Lilianna. “Lili is sort of a filter feeder,” Fena explains, gesturing around the room, which contains everything from an original Tesla coil to a static electricity generator Ed rigged up using parts from an old microwave oven. “She sees all of this stuff floating around and is like, Oh, I can do something with that.”

For instance, when Lilianna was 12, a couple of her swim teammates suffered concussions from backstroking into a wall during a race. “Basically, I hacked a car backup sensor I bought off eBay,” she says, holding up the resulting invention, called Dolphin Goggles, which use the sensor’s technology to alert swimmers when they approach a wall, using lights instead of sound because, as Zyszkowski learned, sound travels differently in water.

The following year, after hearing a story on the radio about infants who died after being left in cars, she came up with the Baby Minder. After a weekend baby-sitting for her 2-year-old cousins, she was inspired to add temperature and moisture sensors to a piece of conductive cloth that, affixed to a diaper, delivered alerts about a baby’s whereabouts, body temperature and diaper efficacy to a smartphone. “I used Bluetooth low-energy, because it had just come out,” Zyszkowski says. “I try to use something new and kind of cutting edge every time.”

During the development process, Zyszkowski says, she often asks her parents for advice. “I bring them ideas and they are, like, How are you going to solve that?”

“We send her links,” says Fena.

“All the time,” Zyszkowski says. “Articles, articles, articles.”

**********

It was an article that alerted Fena that the son of one of her old friends had started Gatekeeper Innovation after a family member had become addicted to pain medication. The company’s story appealed to Lili’s humanitarian instincts, and now she and Gatekeeper have filed a provisional patent for a Safer Lock bottle with PillMinder technology, and they hope to bring the product to market next year. The prototypes she displayed at the White House Science Fair in April showed the device’s evolution. While the original microcontroller was the size of Lili’s hand, the technology had advanced to the point that it fit inside what she calls a “smartcap.” When the cap is removed, a tiny band of LEDs transmits an encrypted message via Bluetooth to a smartphone app, which notifies the patient, or a doctor or caregiver, that the pills were taken—presumably. “One thing I am running into is people saying, ‘If they open the pill cap you don’t know if they actually took the pill or not,’” says Zyszkowski. “But it will still log the fact that they opened the cap and thought about it.”

And there are other benefits, including an ability to link the bottle cap to a pharmacy prescription, a capacity that has intrigued lawmakers looking for ways to stem the illegal distribution of prescription drugs. After the White House Science Fair, Zyszkowski was invited to meet with Senator Richard Blumenthal, the Connecticut Democrat.

“He was having a Senate meeting about trying to figure out where drugs go after the pharmacy, because there’s no, like, trackers,” Zyszkowski says.

Of course, one could argue that using the technology in this way raises questions about personal privacy. Fortunately, Zyszkowski has a panel of experts who can weigh in right at the dinner table. “It’s good to know where drugs are going,” says her mother, the Internet privacy activist. “As long as it’s a need-to-know versus public record. And not everybody will be under surveillance—only things that are aberrations.”

Her daughter nods enthusiastically. “Like, gee, it’s interesting that all of these prescriptions are ending up in the same spot....”

Privacy is important to Zyszkowski, too, especially since she began her sophomore year at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire this fall. One thing you will never see from Minder Industries, she says with a grin, is a Teenager Minder.

“I didn’t invent that for a reason.”