The Long, Fraught History of the Bulletproof Vest

The question of bulletproofing vexed physicians and public figures for years, before pioneering inventors experimented with silk

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0a/ec/0aec6bde-afc2-4086-b9cb-72a4d014c3bc/bulletproof_vest.jpg)

Gavrilo Princip's bullet changed the world. When he fired a bullet and severed an internal vein in the jugular of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914, lodging the projectile into the spine of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, it was as much a turning point for world powers as it was for bulletproofing material and personal protective equipment.

News reports in the days following suggested that Ferdinand had been wearing a type of lightweight undergarment meant to protect him from assassination attempts—a revelation that led some to speculate that Princip had known about the measures and adjusted his aim accordingly. The device would eventually develop into what we know today as the bulletproof vest.

The question of bulletproofing had vexed physicians, public figures, politicians and even monks for years. Nearly three decades before Princip took aim at Ferdinand’s head, a lone doctor in Arizona was working on such an invention.

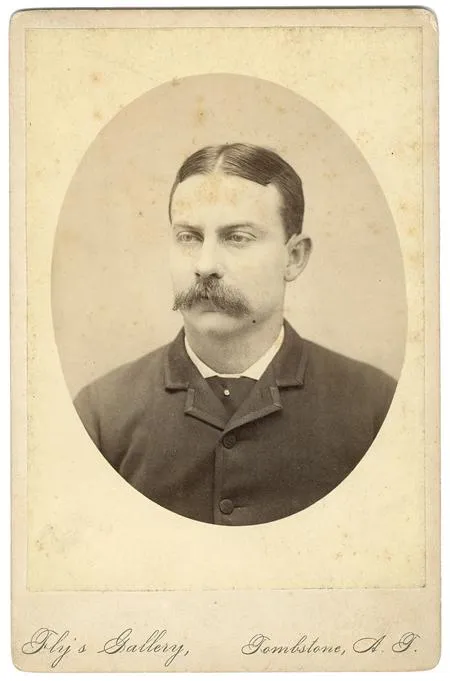

George E. Goodfellow, having been expelled from the Naval Academy for fighting, found himself enamored in the art of treating abdominal gunshot wounds. He performed the first recorded laparotomy (a surgical incision into the abdominal cavity), treated the Earp brothers after their battle at the O.K. Corral and, in an ironic twist, married Katherine Colt, cousin of Samuel Colt, the inventor of the namesake revolver that played a unique role in fomenting his career as America’s top gunshot physician.

In 1881, Goodfellow watched as the trader Luke Short and gambler Charlie Storms shot one another in an altercation on Allen Street in Tombstone (where Goodfellow started his practice, a place he called the “condensation of wickedness”). Both shot from close range.

Storms’ light summer suit caught fire, having been hit with a round from a cut-off Colt 45 revolver from six feet away, and he later died from one of the two bullets fired at him. But the other bullet passed through Storms’ heart. Goodfellow extricated the projectile intact, wrapped in a silk handkerchief (originally in Storms’ breast pocket) that had not torn.

This was one of three incidents where silk saved someone from a bullet wound (another incident involved buckshot and a red silk Chinese handkerchief). And in 1887, six years after the Allen Street shooting, Goodfellow published an article titled “The Impenetrability of Silk to Bullets,” in which he wrote, “Balls propelled from the same barrels, and by the same amount of powder … failed to go through four or six folds of thin silk.” It wasn’t the first attempt at a bulletproof vest using a non-bulletproof material. The Myeonje baegab, a vest from Korea made of layers of cotton, was known to thwart bullets at least two decades prior. But it was progress.

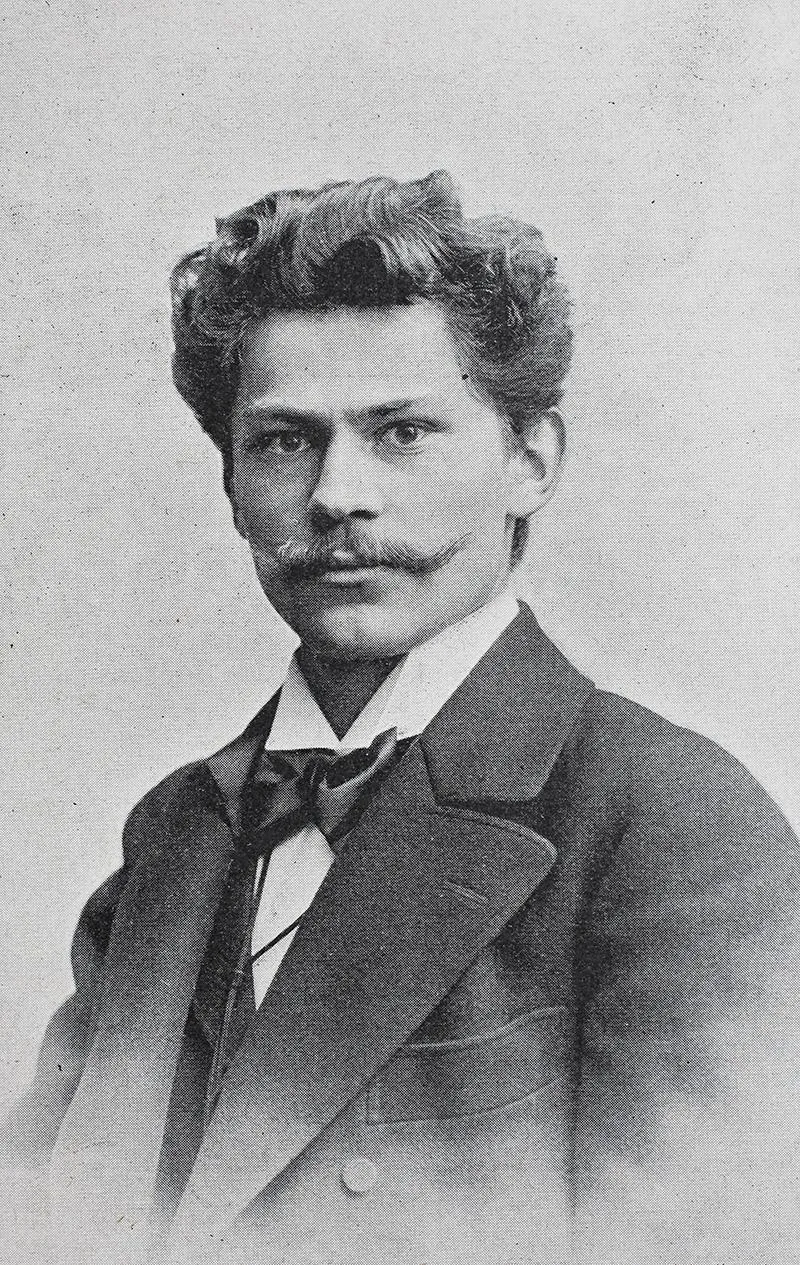

Ten years after Goodfellow’s article was published, on March 16, 1897, in Chicago, a Catholic priest named Casimir Zeglen took his own tightly hand-sewn silk, linen and wool vest—a half-inch thick and weighing half a pound per square foot—and had a pistol marksman shoot him in front of the mayor and other local officials who were plagued by anarchist attacks. (Chicago’s former mayor, Carter Harrison Senior, was murdered at his own house four years earlier). The vest worked. Casimir stood. Copycats, however, proved less effective, as their patterns weren’t as tightly sewn. Without investors, backers and manufacturers, Casimir returned to his native Poland in 1897 and linked up with another Polish inventor, Jan Szczepanik.

What they managed to create, guided by Goodfellow’s own research and writing, was an inflexible bulletproof fabric, a vest they sold for the extraordinary sum of $6,000, adjusted for today’s currency. In the years ahead, the two Polish inventors would clamor with one another for the rights as inventors of the modern bulletproof vest. The vest was a success, worn by dignitaries and royalty.

Roughly 12 years before Princip pulled the trigger and killed Ferdinand, the bulletproof vest made by Zeglen and Szczepanik saved the life of the King of Spain, Alfonso XIII, during an assassination attempt. And throughout World War I, industrialists courted the favor of the Polish duo, hoping they might help propel the German and Austro-Hungary advances to victory.

Civil, foreign and World Wars were fought in a period when even the toughest armor could not stop the most lethal weapon. At the turn of the century, it is observed that protective gear was greatly scaled back, retreating once more from full-body armor to strategically placed metal plates. As battlefields grew farther apart and cannon fire spelled imminent death, and as the fighting grew less personal and more distanced (like the relationship between the men who called the orders to those who marched to them), men wore metal plates over their uniforms and donned metal helmets to protect against gunfire. These plates were placed over the heart, which often beat with a fear that was hardly aided by the presence of a thin metal sheet and, later, a tightly-woven polymer simply known as Kevlar.

Kevlar, or light and ultra-strong plastic polymers that are tightly woven into a flexible fabric, became popular after its discovery and implementation in the 1960s. It is now used in everything from sporting equipment—tennis rackets, Formula 1 cars, boating sails—to personal protective equipment like bulletproof vests.

Despite all the advances in chemical compounds that form some of the strongest materials on Earth, and which are often used to mitigate the damage wrought by firearms or natural disasters, the science that has gone into the fireproofing and weaponization of simple polymers has more recently returned to its Arizona roots.

Two years ago, researchers at the Air Force Research Laboratory announced that they would be looking into an age-old fiber to more fully explore its cooling and temperature regulation properties, and its use toward strengthening current synthetic fibers. That fiber was silk.

Artificial spider silk, the researchers suggested, could make for a lighter, stronger and more breathable body armor than even Kevlar.

Kenneth R. Rosen is the author of the forthcoming Bulletproof Vest. A portion of the book’s proceeds will be donated to RISC, a nonprofit that provides emergency medical training to freelance conflict journalists. For more information, go to www.risctraining.org.