Med School Students Can Play “Operation” With These Synthetic Cadavers

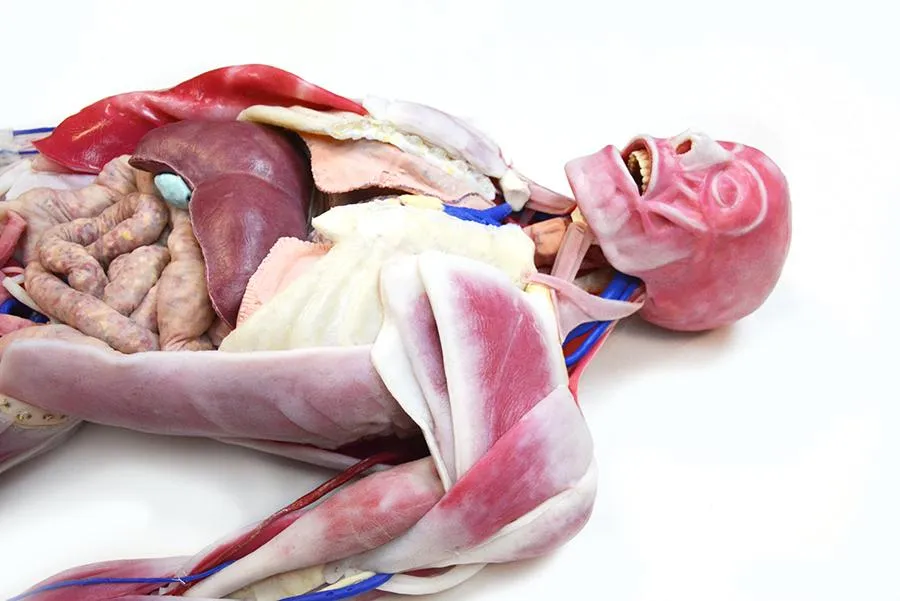

Florida company SynDaver is making life-like organs and bodies. But, as teaching models, are they as helpful as the real thing?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/61/b9/61b9e2f7-8be4-40d0-b407-93a727b3248e/syndaver-main.jpg)

“Dear Organic Human—You are being replaced!”

So reads the first page of the catalog for SynDaver, a Tampa-based company that builds synthetic human bodies for research, anatomy lessons and surgery training. And while the message sounds threatening, the startup might just make medical research smarter and more efficient.

“The model has been called a synthetic cadaver, but really it’s a synthetic live person,” says Christopher Sakezles, the founder of SynDaver. “It’s designed to replace a living person in medical device testing.”

Sakezles got the idea for artificial humans when he was in graduate school at the University of Florida developing medical devices. He was working on building an endotracheal tube—a catheter inserted into a patient's mouth or nose to maintain an airway. His professor had paid a significant amount of money for an artificial trachea to test it. But when it showed up, Sakezles was disappointed with the plastic model.

“I took one look at it and threw it in the garbage,” he says. “With any engineering study, you get out of it what you put in it. At the time, I was studying novel materials, so I decided to develop my own.”

Creating fake organs—and then whole bodies—out of synthetic material is a complicated process. It’s hard to make materials that mimic human tissue, especially if you want it to bruise or cut the same way human skin and muscle might. It took SynDaver almost 20 years to develop SynTissue, which is made primarily of water, salt and fiber, and they’re constantly improving it. They currently have different ways to configure the material to mimic more than 100 different kinds of tissue, from subcutaneous fat to rectus femoris muscle.

“To build a model, you have to have something to mimic, but it’s harder to get your hands on pathology than healthy tissue,” Sakezles says. “It’s hard to mimic materials you can’t get your hands on to test—fibrous lesions on the uterus, for instance.”

SynDaver builds a whole host of things out of the artificial tissue. You can order a femoral artery or a trachea, à la carte, or you can get an entire body. The company's most recent model, the SynDaver patient, comes hooked up to software that lets it mimic body functions. “The surgical models all have a beating heart,” Sakezles says.

The engineer intended for the synthetic cadavers to be used in medical device development. He figured medical technology giants, like Medtronic, would make up his core market, but now the bulk of SynDaver's business is in education. The cadavers are being used in engineering and medical schools. While the company is not marketing the product as a replacement for cadavers in the traditional med school sense, Sakezles sees it as a tool—a way for surgeons to practice specific skills. Engineering students, the most active users, might use one as a more telling crash-test dummy. Someone even donated one to St. Mary’s Dominican High School in New Orleans as a means of teaching high school-level anatomy.

Elizabeth Barker, at the University of Tennessee, was the first professor to bring a SynDaver into her engineering lab. The school didn’t have a facility for cadavers, and she thought her students were missing out on the experience of working with bodies. “It not only gives them an accurate human body model as a reference for their design projects, but also can be used as an experimental tool for testing various device prototypes,” she says.

Unlike a cadaver, which has been frozen, the SynDaver tissue responds more like a live human, so it gives a more accurate reading of how a living person might respond to a car crash or a vent replacement. There are also instances when medical schools can’t get access to bodies that present conditions they want to study. Infant cadavers, for instance, are illegal, because individuals have to be 18 years old to donate their bodies to research.

Medical students at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, have access to SynDavers. "They have these task trainers that are realistic and life-like that they can practice their procedures on prior to doing it on a live patient,” says faculty member and emergency room doctor Teresa Wu in a press release.

But there’s resistance to using the synthetic bodies as teaching tools, especially for high-level anatomy. Some professors don’t think it accurately recreates the experience students would have with human bodies. "You want the student to remember what they saw on the cadaver when they deal with patients later on," Offiong Aqua, an associate professor of occupational therapy and physical therapy at New York University, told Mic. "Using a synthetic cadaver doesn't create the same experience." Although cadavers don’t perform exactly like a living body, all their parts are authentic.

The synhetic cadavers are also expensive (the high-end package of SynDaver's most popular products runs $350,000), and they're fairly time consuming to maintain. Because the tissue is 85-percent water by mass, they have to stay hydrated.

While the SynDaver may be best suited for testing devices, the company says users shouldn't be afraid of cutting, because the body parts can be replaced. “If you create a Y-incision in the skin, it’s there. You can staple it back up, but if you want to make it pristine again you have to replace it. It’s essentially a big 3D jigsaw puzzle,” Sakezles says. SynDaver sells the bodies to schools with a service contract, so they can ship them back to be replaced and repaired every semester.

In May, Sakezles appeared on Shark Tank to try to drum up more funding for the company. He won a $3 million investment from one of the show's celebrity investors, tech mogul Robert Herjavec, but the deal fell through because of differences in opinion on how to restructure the business.

Nevertheless, the business is growing. SynDaver is developing more infant and adolescent models and working with physical therapists, sports scientists, even veterinarians, who may be interested in synthetic animals.

"The reach of technology means we can get into more areas," Sakezles says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0196_2.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0196_2.JPG)