Meet Marion Donovan, the Mother Who Invented a Precursor to the Disposable Diaper

The prolific inventor with 20 patents to her name developed the “Boater,” a reusable, waterproof diaper cover in the late 1940s

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/a1/c3a11467-d58f-4edc-8dfe-1eea8f00bf54/marion_donovan.jpg)

I’ve got a baby and a toddler, and I don’t go anywhere without diapers. They’re in my laptop bag and my husband’s briefcase, in my hiking backpack, stashed in all the suitcases, tucked away in the glove compartment of every car I ever borrow. They’re such a ubiquitous feature of parenthood I’ve hardly ever thought about what life would be like without them. But until the mid-20th century, diapering babies meant folding and pinning cloth toweling, then tugging on a pair of rubber pants.

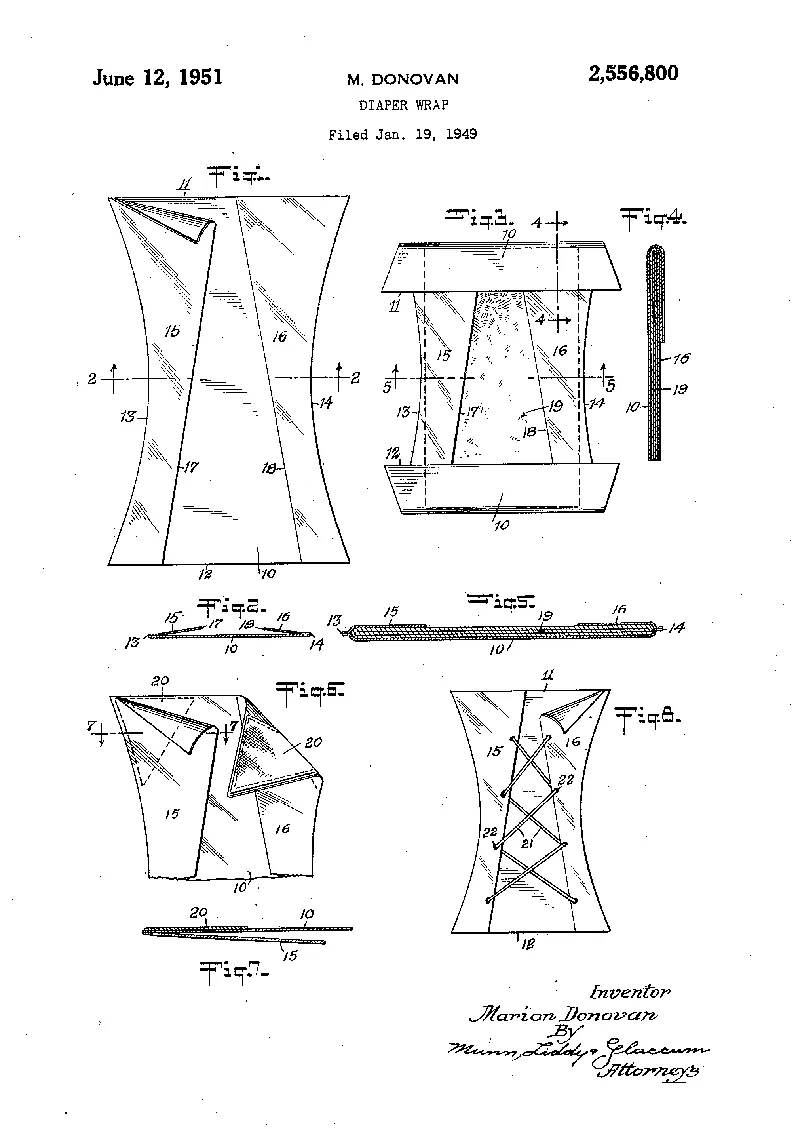

In the late 1940s, a woman named Marion Donovan changed all that. She created a new kind of diaper, an envelope-like plastic cover with an absorbent insert. Her invention, patented in 1951, netted her a million dollars (nearly $10 million in today’s money) and paved the way for the development of the disposable diaper as we know it today. Donovan would go on to become one of the most prolific female inventors of her time.

Donovan was born Marion O’Brien in South Bend, Indiana in 1917. Her mother died when she was young, and her father, an engineer and inventor himself, encouraged her innovative mind—she created a new kind of tooth cleaning powder while still in elementary school. After graduating from college, she went to work as an editor at women’s magazines in New York, before marrying and settling in Connecticut.

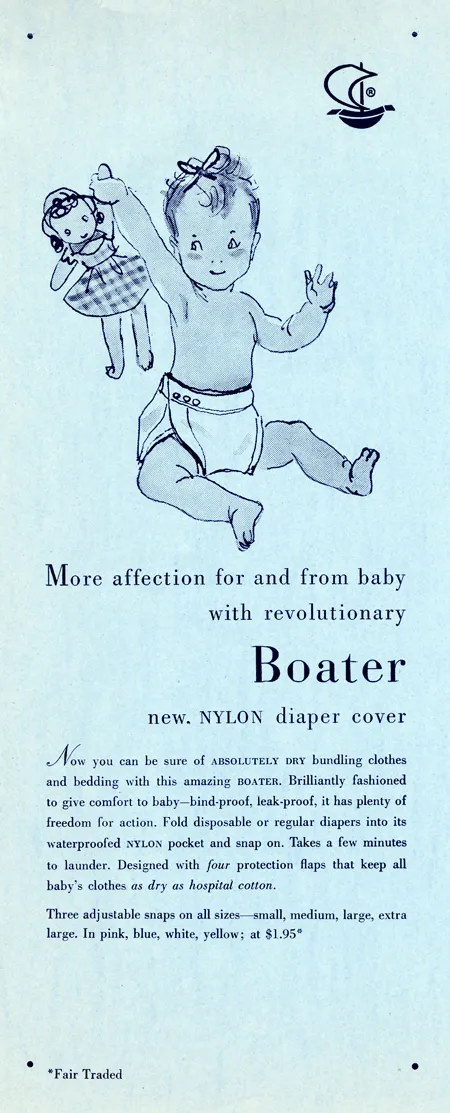

It was there, as a young mother sick of changing wet crib sheets, that Donovan had her lightning bolt moment. In her opinion cloth diapers “served more as a wick than a sponge,” while rubber pants caused painful diaper rashes. So she decided to make something better. She pulled down her shower curtain, cut it into pieces, and sewed it into a waterproof diaper cover with snaps instead of safety pins. That led to a diaper cover made from breathable parachute cloth, which had an insert for an absorbent diaper panel. Donovan named it the “Boater.”

Manufacturers, though, weren’t interested. As Donovan would tell Barbara Walters in 1975:

“I went to all the big names that you can think of, and they said ‘We don’t want it. No woman has asked us for that. They’re very happy, and they buy all our baby pants.’ So, I went into manufacturing myself.”

In 1949, she started selling the boater at Saks Fifth Avenue, where it was an instant smash hit. Two years later she sold her company and her patents to Keko Corporation for a million dollars. Donovan considered going on to develop a diaper using absorbant paper, but executives at the time allegedly weren't interested. Pampers, the first mass-produced disposable diaper, wouldn't hit the market until 1961.

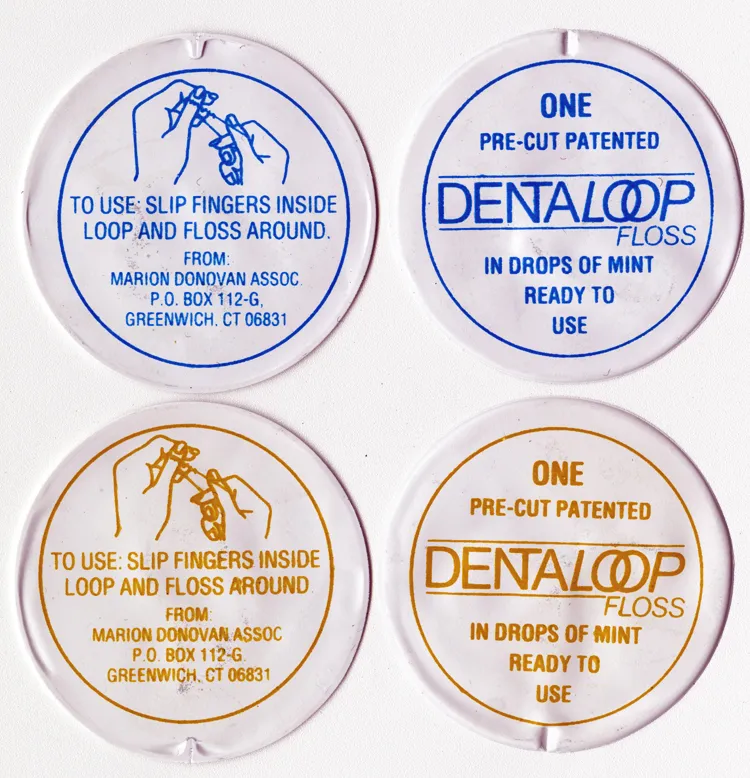

The boater wasn’t the end of Donovan’s inventions. She went on to earn a total of 20 patents, for things from a pull cord for zipping up a dress with a back zipper to a combined check- and record-keeping book to a new kind of dental floss device.

After Donovan died in 1998, her children donated her papers to the Archives Center at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History; the acquisition was part of the Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation’s Modern Inventors Documentation Program. The 17 boxes of artifacts contain notes, drawings, patents, customer orders, advertisements, newspaper articles, a scrapbook, personal papers and photographs. The collection is used frequently by scholars, mainly people studying women's history or the history of technology, says Lemelson Center archivist Alison Oswald.

"Her collection is fairly comprehensive for a woman inventor of this time period," says Oswald, who acquired the collection for the archives. "We're really fortunate that her family had saved as much as they did, because invention records can be pretty fragmented."

Donovan's daughter Christine recalls growing up in a house that doubled as an R&D lab.

"Mom was always drawing or working with materials—wire or plastic or nylon or paper," she says. "She had an office above the garage, but frankly, everywhere was her drawing board. The kitchen was often where Mom was, and something was always cooking, but not food—heating irons and sealants and so on."

Christine and her brother and sister would often help their mother with her inventions. "I remember working with her on putting the snaps into the boater's nylon diaper cover," she says.

Donovan also earned a degree in architecture from Yale in 1958, one of only three women in her graduating class. She would later design her own home in Connecticut.

As remarkable as Donovan was, to her children a life of at-home assembly lines and solvents bubbling away on the stovetop was perfectly normal. As Christine says, "Mom was Mom, and we didn’t know anything else."

This Mother’s Day I’ll be thinking of my own mother, who changed thousands of diapers while raising three children and still happily lends a hand with her grandchildren. But I surely have a warm spot in my heart for Marion Donovan, whose curious and inventive mind made life easier for millions of parents.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)