Meet the Product Designer Who Made Mid-Century America Look Clean and Stylish

From refrigerators to cars to Air Force One, Raymond Loewy’s distinctive “cleanlining” sold products

:focal(502x152:503x153)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/30/df3059c3-7614-4604-9a55-c14f60a9211d/raymond_loewy.jpg)

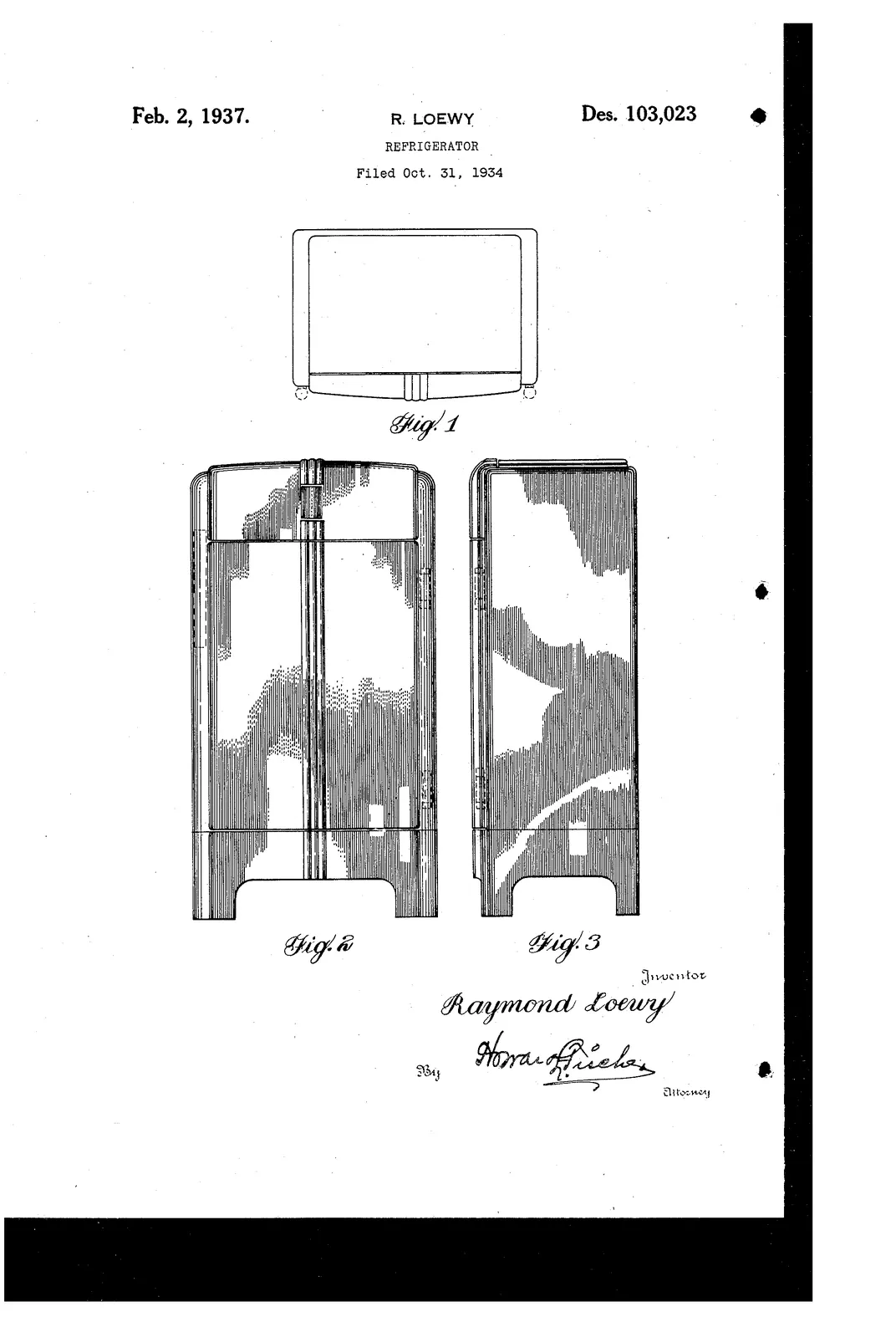

Raymond Loewy, the legendary American product designer and businessman, isn’t familiar to consumers today, but in the latter half of the 20th century he was a household name for his practice of applying the principles of what he called “cleanlining” to create starkly memorable designs. The 1934 Sears refrigerator; the packaging for Lucky Strike cigarettes; the Exxon logo; dozens of car models for the Studebaker Automobile Company—all were Loewy’s designs. Following his credo that “the loveliest curve I know is the sales curve,” Loewy moved millions of products for clients such as Coca-Cola, Nabisco, Armour and Frigidaire.

The French-born Loewy also applied the tenets of cleanlining—reducing the look of a product to its essence, without frills or needless detail—to build his own uniquely American persona. Reinvention is a recurring theme in American literature and legend, and like the products he re-envisioned, Loewy, too, managed his public image from the moment he immigrated to the United States, continually editing and polishing his biography over more than a half-century as he worked as a designer and artist. He built one of the most successful design firms in history, and positioned himself as “America’s designer” through society connections, media and the advertising methods now known as branding.

His achievements took place in a rapidly expanding consumer culture. In the decades after World War I—stretching through the Great Depression, another world war and into the 1960s—American consumer products transformed. Touring cars metamorphosed from boxy, front-heavy behemoths to vehicles with balanced proportions. Tractors, formerly hulking machines studded with belts and gears, became compact workhorses with ergonomic seats, maneuverable rubber tires and protected engine components. The proliferation of stylish consumer goods inspired a spending spree among the expanding middle class who wanted new products, appliances and experiences with designs to match their own optimism. The nation’s gross domestic product jumped from $228 billion in 1945 to more than $1.7 trillion in 1975.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/aa/1daad4cb-e52a-47fe-b3d3-b28e3f6dcfb3/lowey_kitchen.png)

The transformation was driven by a new American discipline: industrial design. Industrial designers mined principles they had learned in theater, architecture, advertising and art to create irresistible products. Norman Bel Geddes, designer of the “Futurama” exhibit at the 1939 World’s Fair, was a bombastic theater designer who wrote Horizons, an influential book filled with illustrations of streamlined planes, trains and automobiles. Walter Teague, best known for Kodak’s Brownie cameras with their black and yellow packaging, had a background in advertising illustration. Henry Dreyfuss, creator of the Honeywell round thermostat and the modern AT&T handset telephone, transformed himself from a theater designer into a specialist in ergonomic design.

But Loewy was the most influential American industrial designer of them all. He was born into privilege in Paris in 1893, the son of a business journalist father and a driven mother whose mantra was “it is better to be envied than pitied.” Loewy studied engineering at Ecole de Lanneau, France’s preeminent technological university, and was drafted into the French army as a private during World War I. He fought along the Western Front, and was awarded the Croix de Guerre for crawling into no-man’s-land to repair communication lines. He eventually rose to the rank of captain.

After the armistice, Loewy came back home. His parents had both died in the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. France itself had been devastated by war, and Loewy soon decided to join his brother, who had moved to New York City. In 1919, during his ocean voyage to the U.S., Loewy entered a sketch into a shipboard talent contest. The drawing caught the eye of fellow passenger Sir Henry Armstrong, the British consul in New York, who promised to introduce the young captain to potential employers. Loewy hit the streets armed with Armstrong’s letter of recommendation and a portfolio of drawings.

By 1920, Loewy had carved out a solid niche as a fashion illustrator, establishing a nationwide reputation for his art deco-inspired fashion ads and catalogues, as well as travel ads featuring sleek ships for the White Star Line. He was very successful, making upwards of $30,000 a year (about $381,000 in today’s dollars). But by 1929 Loewy was growing unsatisfied with life as an illustrator, and he began to think he could make a bigger impact by transforming American products themselves. “Financially, I was successful but I was intellectually frustrated,” he told the New York Times late in his life. “Prosperity was at its peak but America was turning out mountains of ugly, sleazy junk. I was offended my adopted country was swamping the world with so much junk.”

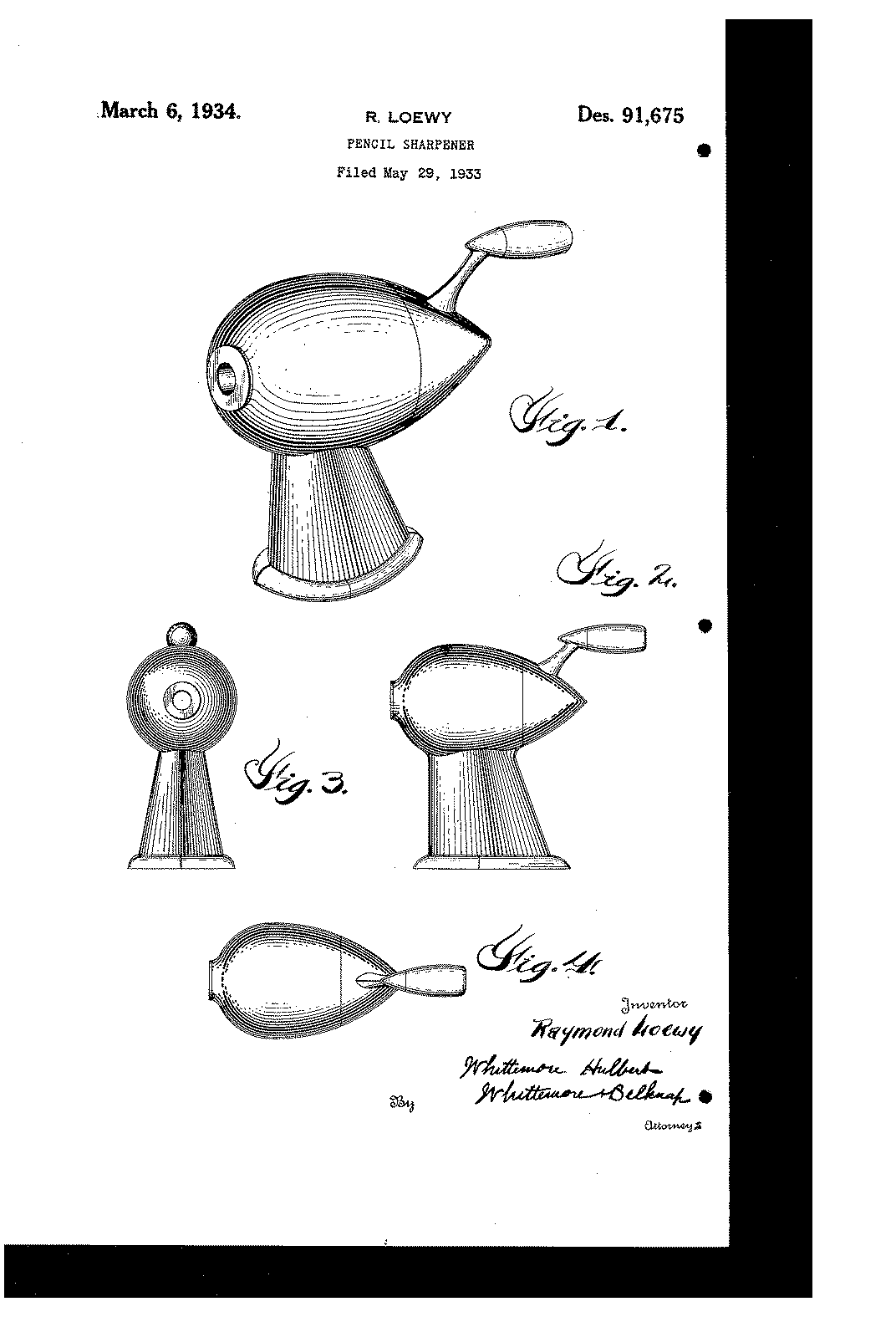

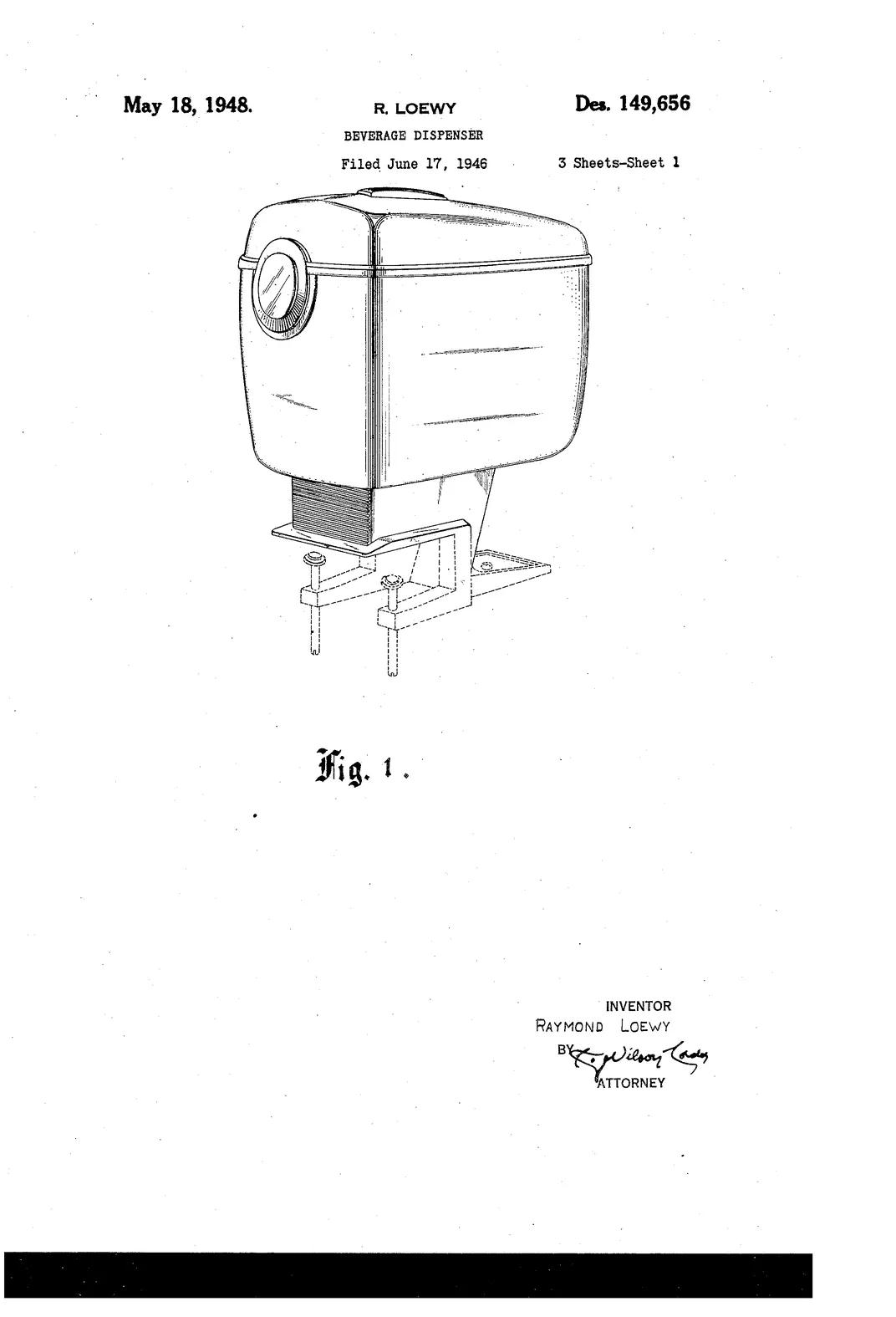

He dove into design. His first project was revamping a Gestetner duplicator, an early version of an office mimeograph machine, by creating a streamlined shell to hide most of the machine’s unsightly moving parts. Sigmund Gestetner, the London-based businessman who made the copier, accepted Loewy’s design in 1929, paying $2,000 (about $28,000 today), which Loewy used to launch his firm. He hired designers and a business manager, but in the midst of the Great Depression clients were scarce. Loewy needed something beyond talent. He needed an image.

He settled on a mix of old-fashioned American pushiness and Euro-suavity—sporting a dapper mustache and wearing the latest French fashions—and hit the road to sell his vision to Midwestern manufacturing executives. His pitch was simple and emblazoned on his business cards: “Between two products equal in price, function and quality, the better looking will outsell the other.” Throughout his career, Loewy made all major client pitches and presentations and then turned account service over to subordinates.

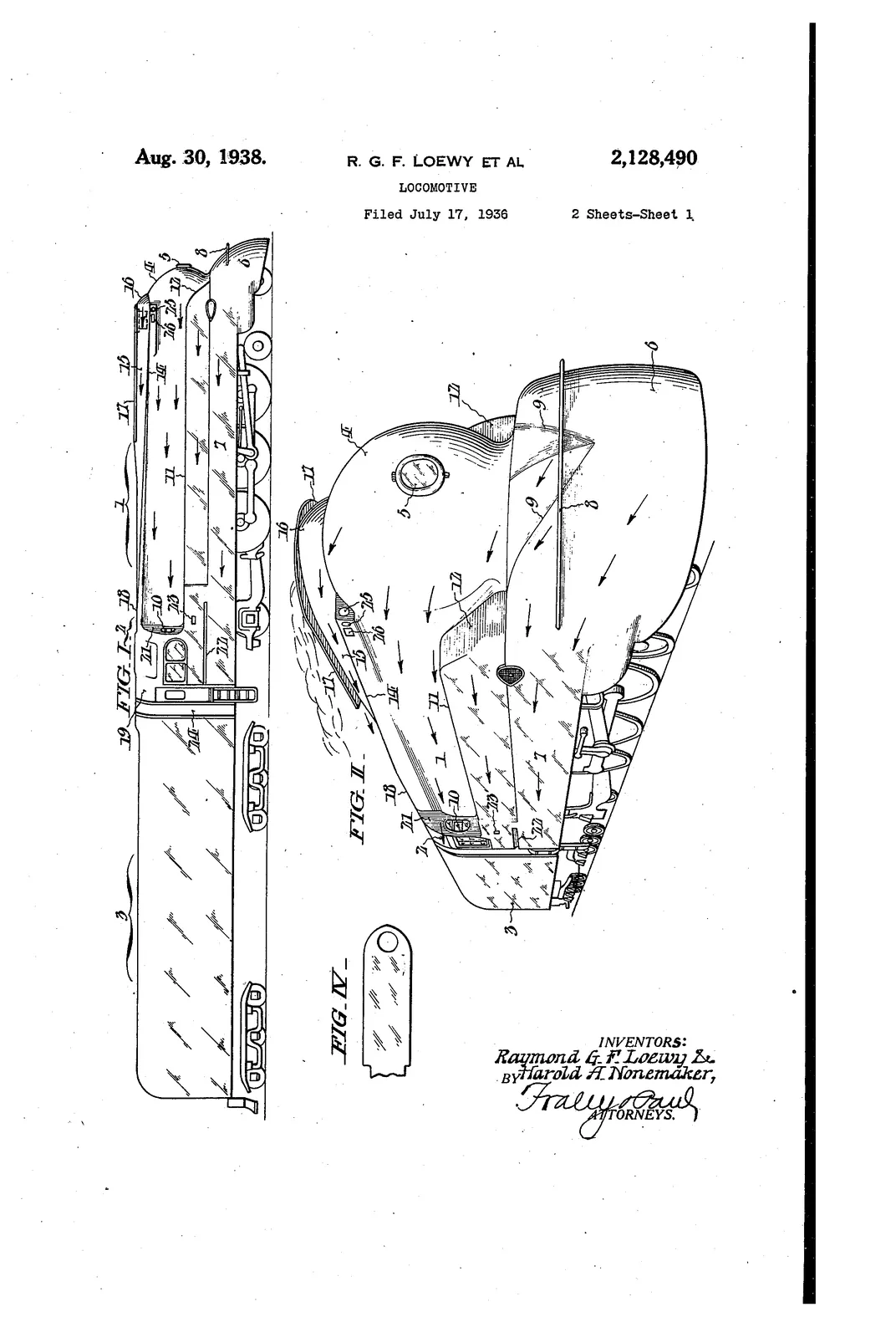

Companies fell hard for Loewy’s charm. Sears asked him to design a refrigerator, and he produced the 1934 Coldspot, a gleaming white shrine to streamlined purity that increased sales from 15,000 to 275,000 units in five years. Loewy convinced the Pennsylvania Railroad to let him design a garbage can for New York’s Penn Station, producing a bin that incorporated art deco designs with the Egyptian motifs popular after the 1922 discovery of King Tut’s tomb. Delighted, the railroad went on to commission the PRR GG-1, an electric locomotive with swooping curves, and the PRR S-1, a streamlined locomotive resembling a speeding bullet. The S-1 was the largest steam locomotive ever built—and so distinctive that critics and high society considered it a work of art when it was exhibited at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. The engine, which chugged in place on a treadmill, drew thousands of visitors per day and was considered the star of the fair.

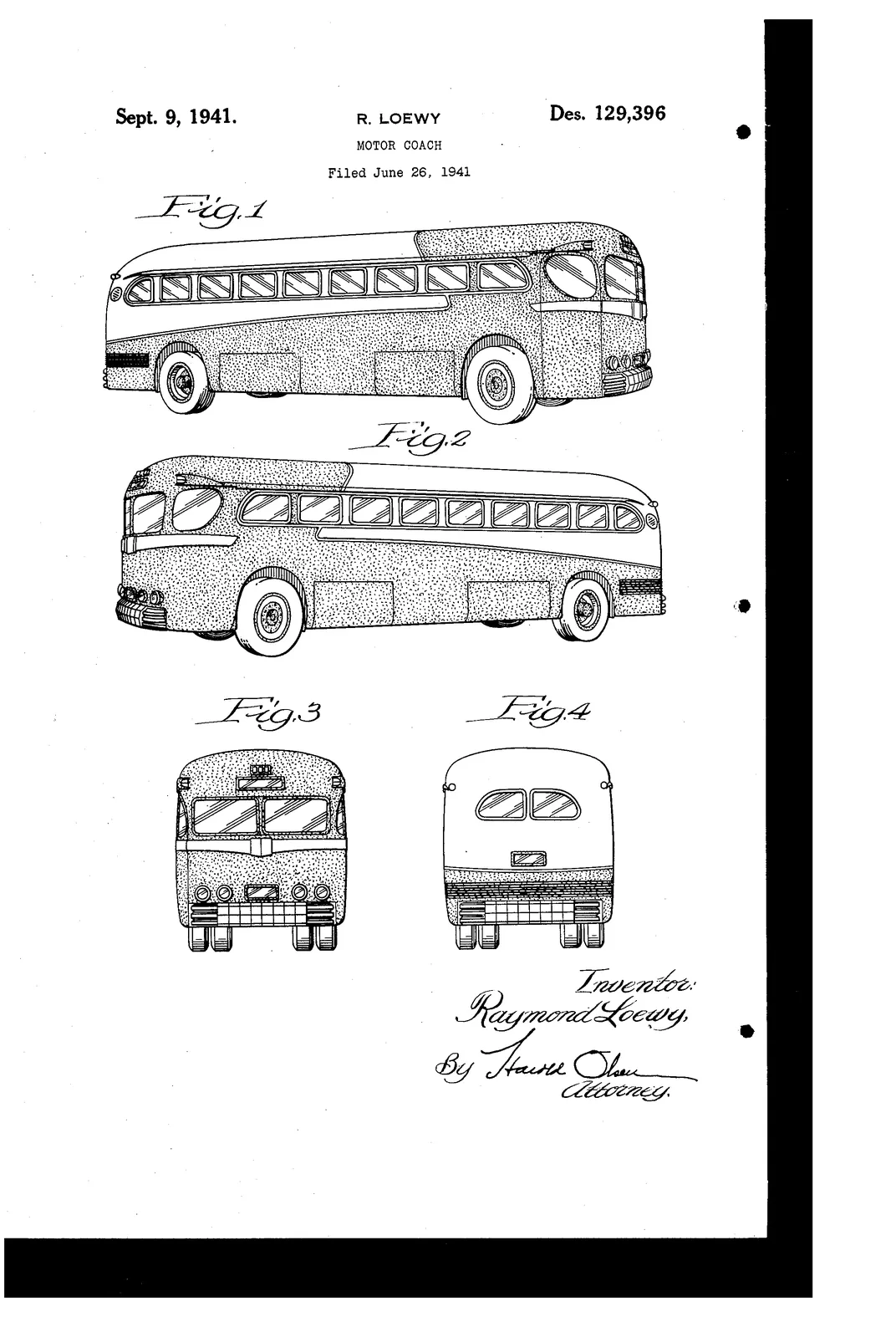

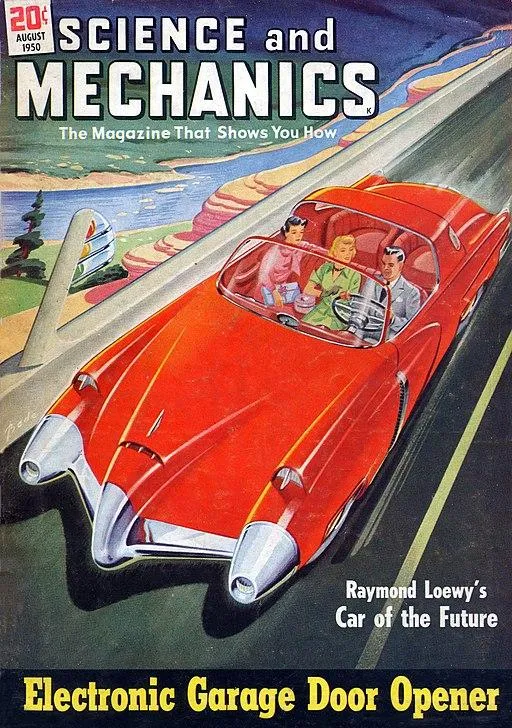

By the 1940s Loewy was designing for Greyhound, International Harvester, American Tobacco and Coca-Cola, but he became best known as the main automotive designer for the Studebaker Automobile Company. Loewy’s European background set him apart from the U.S.-born car designers in the design studios for General Motors, Ford and Chrysler. The innovative 1947 Commander, for instance, had a unified body, equally balanced in the front and the back, with sleek trim meant to mimic the fighter planes of World War II. The car was a hit with consumers, vaulting Studebaker to fourth place in sales behind GM, Ford, and Chrysler. Praised by auto writers as “forward leaning,” the Commander led the way to the company’s best sales years. By 1950, when it moved 268,229 cars out of showrooms, Studebaker owned 4 percent of the domestic car market.

The 1953 Starliner coupe was Loewy’s first legitimately revolutionary car design. The Big Three automakers designed cars for American highways, with front seats like sofas and cushiony suspensions that barely registered when drivers ran over debris. Loewy and his team saw a need for a smaller car that emphasized gas mileage and a superior road feel. The Starliner sat low to the road, had minimal chrome, and a de-emphasized grille; its aerodynamic beauty presaged such “personal” cars as the Corvette, the Thunderbird, the Mustang and the Buick Riviera. Car designers would not make a similar great leap forward until Ford redesigned the Thunderbird and Taurus in the 1980s.

Loewy’s crowning automotive achievement was 1963’s Avanti. The fiberglass-bodied sports car featured razor-like fenders sweeping into a raised rear end, a wedge-shaped front end, and safety features including a roll bar, disc brakes and a padded interior. The interior, a direct steal from airliners, featured an overhead console and controls that resembled jet throttles. The overall effect was a startling silhouette, unequaled to this day.

Loewy’s commissions grew with the explosive postwar economy, and so did his reputation. He hired a staff of junior designers, took on several partners in packaging and retail space design, and most importantly, hired Betty Reese as his press agent. Loewy and Reese established the modern standard for creating a brand. Reese taught Loewy to turn every product design debut into a Hollywood production. She counseled him to shove his way into a photo if he saw a press photographer. He learned where to stand in photographs—front row, far left, because editors identify people in photos from left to right. He customized existing car models and drove his one-off designs to public events. His homes were intended less as residences than as advertisements for himself: the New York apartment stuffed with art and Loewy-designed products, the house in Palm Springs featuring a pool that extended into the living room.

Everything was in service to Loewy’s image—and soon enough, his name and photograph were featured in publications across the country. Loewy came to personify the term “designer” and journalists sought him out to comment on everything from GM cars (“jukeboxes on wheels”) to eggs (“the perfect design”). The culmination of his branding triumph came in 1949, when he was the subject of a cover story in Time magazine and of an extensive feature in Life. He followed up with Never Leave Well Enough Alone, an “autobiography” that eschewed biographical detail for a litany of his design triumphs, all conveyed in his singular, charming voice. One critic called it “a 100,000-word after-dinner speech.” The book, which remains in print today, represented the culmination of Loewy’s image-making.

In his later years, Loewy would create more iconic designs: Air Force One; logos for Exxon, Trans World Airlines and the U.S. Postal Service; and the interior of the Concorde supersonic airliner. He worked relentlessly until he sold his company in 1979.

Shortly thereafter Loewy’s aura diminished. In a sense, his longevity had worked against his legacy, because he was rarely offstage long enough to inspire a revival of his influence. Today, Loewy’s influence is still hotly debated by design historians and art critics. One camp admires his genius for popular design influence while the other side insists he was primarily a businessman who took credit for his employees’ designs.

What is clear is that his vision succeeded wildly in the marketplace and remains influential. His logo for International Harvester—a black “H,” which represents the oversized tractor wheels, interlocked with a red dotted “i” that signifies the tractor body and the farmer or driver—is still seen today on trucker hats, T-shirts and bumper stickers—33 years after the company went out of business.

Just as significantly, the template Raymond Loewy created to make himself a nationally known personality has morphed into the modern science of branding. If he were designing toasters and cars today there is no doubt—with apologies to other compulsive American communicators—that he would be the king of all media.

John Wall is a retired journalist, a higher education media relations specialist and the author of Streamliner: Raymond Loewy and Image-Making in the Age of American Industrial Design.