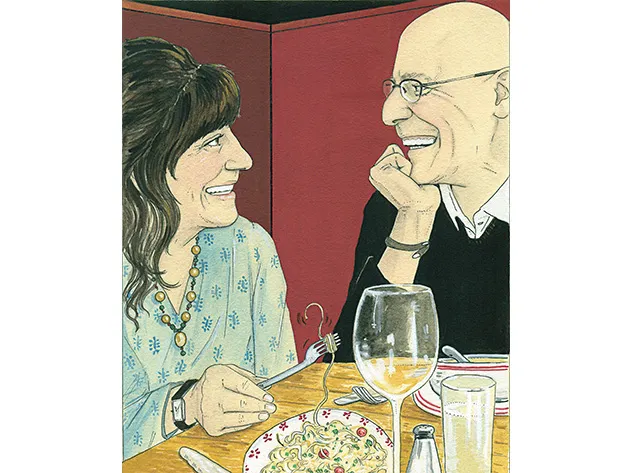

Michael Pollan and Ruth Reichl Hash out the Food Revolution

Be a fly in the soup at the dinner table with two of America’s most iconic food writers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/American-Table-Michael-Pollan-Ruth-Reichl-631.jpg)

The biggest problem was figuring out where to eat.

When you live on opposite sides of the country and have wildly conflicting schedules, choosing a restaurant is the least of your troubles. Michael Pollan and I couldn’t even figure out on which coast we wanted to dine. We finally settled on the East, but that still left the choice of town. For various (not very interesting) reasons, we ended up in Great Barrington, Massachusetts.

After that it was easy; Bell & Anchor was the obvious choice. Proprietor Mark Firth left Brooklyn (where he’d been a restaurant pioneer with Diner and Marlow & Sons) to become a farmer in the Berkshires. But he’s a relentlessly hospitable fellow, and last year he opened this relaxed and rustic restaurant to serve what he and his neighbors raise. The restaurant has become a local hangout for people who are passionate about the ethics of eating. Everything Michael and I ate had been sustainably and humanely raised, and much of it came from within a few miles of where we sat. As we discussed the culinary revolution, the future of food and his new book, Cooked, we were literally eating our words.—R.R.

Ruth Reichl: The thing that’s so odd is you’ve sort of become the voice of food for Americans but you didn’t start off as a cook.

Michael Pollan: Not at all. My whole interest in food grew from my interest in gardens and the question of how we engage with the natural world. To go back even further, I got interested in gardens because I was interested in nature and wilderness and Thoreau and Emerson. I brought all their intellectual baggage to my garden here in New England and found that it didn’t work out very well, because ultimately Thoreau and Emerson’s love for nature was confined to the wild. They didn’t conceive of a role for us in nature other than as admirer and spectator...which is a problem when a woodchuck eats all your seedlings. What do you do?

Waiter offers some wine.

R: Oh! This reminds me of one of those amphora wines ! They are peculiar. You feel like this is what wines in Greece must have tasted like 1,000 years ago. It’s everything Americans don’t like. It’s totally not charming.

P: It’s definitely not charming. It requires you to pay attention. So where was I? So, much of my work grew out of this wonderful American tradition of nature writing, which I was steeped in in college and graduate school. The first food story I wrote was called “Cultivating Virtue: Compost and Its Moral Imperatives,” about American attitudes toward gardening, which are uniquely moralistic. That became the first of a series of essays looking at the interaction between Americans and nature in a place that wasn’t the woods, wasn’t the wild. Ever since I’ve been interested in these messy places where nature and culture have to mix it up. And of course food—the plate—is the most important place. Though I didn’t realize that at the time. First it was gardens and then the garden led to agriculture and agriculture led me to food.

R: But it must be hard. You now have this burden on your shoulder. You’re sort of responsible for all of American food in some way.

P: I’m doing a pretty bad job if I am.

R: You’re doing an amazing job. Before The Omnivore’s Dilemma [in 2006], I was out there begging people to pay attention to this stuff. In fact, what I loved so much about your book is that what you were saying is: “We will be better if we cook.” And that’s what we all were feeling in the ’70s. Go back into the kitchen. This is the one place you can control your life.

P: The conversation about food does begin back in the ’70s. People don’t realize it. They think the food movement began with me, or with Eric Schlosser [who wrote Fast Food Nation in 2001].

R: For me it began with Frankie Lappé. Changed my life. Diet for a Small Planet, 1971.

P: I didn’t read that then, but I soaked up what came out of it. She was the first person to connect the dots between the way you ate and the environment and the fate of people in Africa. That was a mind-blowing book.

R: I was just, “Oh my god, almost 20 pounds of animal feed to make a pound of steak. This is insane!” Everybody I knew started thinking: “This is where we take control, this is the next fight for us.” A bunch of radicals looking around and saying “What do you do after you end the war in Vietnam?” I lived in a commune, basically. We cooked together and we tried growing our own food. And dumpster diving.

P: Have any gardening tips?

R: I wasn’t the gardener.

P: But you had land?

R: We had a big backyard. You can grow a lot in a backyard.

P: I know. I do it in my front yard now, which is a postage stamp. And then there was Wendell Berry and his The Unsettling of America. And Barry Commoner was writing about agriculture too and the energy that went into growing food. It was the start of something, the outlines of a food movement—and then it was kind of aborted in the 1980s.

R: I think in Berkeley it suddenly shifted and it becomes about deliciousness.

P: Was that Alice Waters’ [of Chez Panisse] doing?

R: I think it was everybody’s doing. When you go from the industrialized food of the ’50s and ’60s and you suddenly get more serious about cooking and start thinking, “How do I make this better? Maybe I can make my own sausage.” A lot of that energy just shifted into learning to cook.

P: It became about craft. And the politics were de-emphasized.

R: And the money equation came into it. Suddenly, hippies who were growing gardens were successful.

P: The early food movement was rooted in ’60s culture. What happened in the ’80s was a reaction against ’60s culture in all respects.

R: Oh definitely. For me it was.

P: I think for a lot of people. We had this huge backlash against ’60s culture during the Reagan years, and at least nationally, the food movement went away for a while. And then it revived in the early ’90s. The Alar episode was a galvanizing moment. Do you remember that? 1989, “60 Minutes” opened the floodgates, Meryl Streep spoke out and there was a big cover story in Newsweek. People got freaked out about the practice of spraying this growth regulator on apples, which the EPA had said was a probable carcinogen. Mothers stopped buying apples all at once—or insisted on buying organic. That’s when organic kind of took off nationally. I wrote a lot about the history of the organic industry in The Omnivore’s Dilemma and experts all date its rise to that moment. That’s when you suddenly could make money selling organic food nationally. And then you had other food scares in the ’90s that contributed. What year is the scare over mad cow disease? Mid-1990s? Remember?

R: It’s definitely mid ’90s. I was a food editor at the L.A. Times, but I stopped in ’93 and mad cow was definitely after ’93 because we would have been right on top of it. [It was 1996.]

P: So that was another big episode, even though it was mostly confined to Europe. We didn’t know if it was going to come here and we learned all these horrifying things about how we were producing beef and that too generated a lot of interest in the food system and was probably one of the reasons Eric [Schlosser] wrote Fast Food Nation.

R: People didn’t really focus on what was really going on. It wasn’t like The Jungle until Fast Food Nation.

P: He pulled it all together: What you were served in a fast-food restaurant, the farmers and ranchers, the restaurant workers, and then everything that stood behind it. That was a really important book in terms of waking people up to the hidden reality of the things they were eating every day.

R: Absolutely. Although conditions in meatpacking haven’t changed at all.

P: That’s not quite true. You do have the whole Temple Grandin project of making slaughterhouses more humane. [Temple Grandin is a designer who uses behavioral principles to control livestock.]

R: Yes, that was a big moment when McDonald’s hired this brilliant autistic woman to improve the way the cattle were slaughtered. The animals’ conditions have gotten better. Right. So now we think the best day of their lives is the day they die. But the workers’ conditions, that’s the part that...Farm workers, meat workers, supermarket workers. These jobs are awful.

P: I think the next chapter of the food movement will involve paying more attention to the workers in the food chain—on the farm, in the packing plants and in the restaurants. To a lot of people who care about food, all these people are invisible, but that’s starting finally to change. I think the campaign by the Coalition of Immokalee Workers to improve the pay of tomato pickers in Florida has been an interesting and successful fight, one that much of the food movement supported.

R: I’d like to think we at Gourmet [where Reichl was editor in chief from 1999 to 2009] had a hand in that. I sent Barry Estabrook down to Florida to write about the conditions of the tomato pickers, who were living in virtual slavery. They’d been fighting, unsuccessfully, to get a penny per pound raise from the growers. After the article appeared the governor met with them, and they won their fight.

The waitress arrives.

P: Oh, we have to do some work. Give us a minute. Do you have any specials we need to know about?

Waitress: No, everything on the menu is a special because the menu changes every day.

P: So pork is what they did themselves. All right, I’m going with that.

R: I remember their chicken as being really delicious. I love that they’ve got beef heart. Not that I’m wanting it, but I love that they have it.

P: Somebody’s got to order it, though.

R: I ate a lot of beef hearts in Berkeley. It was so cheap. We ate a lot of hearts of every kind because you could get them for nothing.

P: Great menu.

R: Braised pork with farro. That sounds delicious.

P: I have to try the chick pea soup because I have to make one this week.

R: They have their own hens. Maybe we need to have their deviled eggs. I’m going to have eggs and chicken.

Waitress: OK, thanks.

P: So where were we? So yes, I think Schlosser’s book is a big deal and in fact it led to me writing about these issues because my editors at the New York Times Magazine saw this totally surprise best seller and said, “We want a big cover story on meat.” And I’m like, “What about meat?” And they said, “We don’t know, go find a story about meat.” And I went out and did that story that became “Power Steer.”

R: That piece was so amazing because you really managed to make us feel for these people who were doing such terrible things.

P: My editor in that case deserves a lot of credit because I was utterly lost in that piece. I got immersed in all the different issues tied to beef production, from feedlot pollution to hormones and antibiotics to corn. I was drowning in amazing information. My editor took me out to lunch and I did the data dump and he starts to glaze over. Then he says, “Why don’t you just do the biography of one cow?” That was brilliant. I immediately saw how you could connect the dots. And I saw how you could meet people exactly where they are—eating their steaks or burgers—and take them on a journey. I was very careful to tell people at the beginning of that story that I ate meat and that I wanted to keep eating meat. Otherwise, people would not have gone on the journey with me.

R: And the other thing that you did that was so smart was to make the ranchers sympathetic. Because they are. They’re caught between a rock and a hard place.

P: They’re selling into a monopoly. It’s a terrible predicament and they really resent it. They’re doing things the way they’ve always done them, only the market is more concentrated and they’re under enormous pressure. I was very sympathetic to them, though they weren’t pleased with the story.

R: But that’s when you’re really successful. If the people you write about like it too much, you probably haven’t done the right thing. But I do think that Omnivore’s Dilemma was a really major moment. Again, a surprise best seller. Who would have thought?

P: I didn’t. I was shocked because, first of all, I thought, “I’m late on this, this issue has peaked.” But I can remember the moment where I sensed that there was something going on. It was at the Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle, at the beginning of the tour in the spring of 2006. I went there to find a huge crowd hanging from the rafters and screaming as if it were a political rally. There was this energy unlike anything I ever experienced as an author. I could feel it during that book tour that the culture was primed to have this conversation.

R: At Gourmet we were all talking about that but we hadn’t put it together in a satisfying package. And so what Frankie Lappé was for me, Omnivore’s Dilemma was for my [college-age] son Nick. This is not a deeply political generation, so it gave them something.

P: Food is definitely one of the defining issues for this generation.

R: It’s a cause his generation can feel good about. I’d say half of Nick’s friends are vegetarians for ethical reasons and a quarter of them are vegans and I think that’s not uncommon.

P: Their food choices are central to their identity. And they’re more fanatical than older generations. I’m always meeting them and I’m like, “Wow, you are really a purist.”

R: It’s become an identity issue.

P: It’s empowering, for them—for everyone. Food choices are something fundamental you can control about yourself: what you take into your body. When so many other things are out of control and your influence over climate change—all these much larger issues—it’s very hard to see any results or any progress. But everybody can see progress around food. They see new markets rising, they see idealistic young people getting into farming. It’s a very hopeful development in a not particularly hopeful time.

R: And it’s something we all do. We’ve all been shouting for a long time, “You vote with your dollars.” And it feels like when you shop in the right place, you shop in your community, you are personally having an impact.

P: And they see the impact because the markets are growing. There’s this liveliness at the farmer’s market and this sense of community, too. Which, of course, food has done for thousands of years.

R: But had not in America for quite a while. It had to be rediscovered.

P: So when you started running stories in Gourmet about agriculture and the environment, how did that go over? This was a magazine that had been about pure consumption.

R: I went in and asked the staff, “What should we do?” And they all said: “We should do a produce issue. We need to pay attention to what’s going on in the farms.” And I was thrilled because I thought I was going to have to convince all of them and they were way ahead of me. This is 2000. And my publisher was really appalled. It’s not sexy. There was nothing sexy about farming. Although now there’s a magazine that just launched called Modern Farmer.

P: I know! I haven’t seen it yet.

R: The big problem of trying to do this in magazines is just about every story I did that I was really proud of, the publisher had a problem with. We did this story about how the trans fat food industry set up a task force to heckle every scientist who was working on trans fats for 30 years. They knew for 30 years how bad this stuff was and they had gone to the medical journals and stopped everything that they could. It was an incredible story.

P: It parallels, obviously, the tobacco companies. When they were exposed as lying about their products, that’s when they really ran into trouble. That line that “We are just competing over market share, we’re not actually stimulating people to smoke or overeat.” You don’t spend billions of dollars on marketing if it’s not working. And they understand that it’s more profitable to get a soda drinker to double consumption than to create a new soda drinker, so the focus on the heavy user is part of their business model. Those revelations have been very damaging.

R: Soda is fascinating to me because I think it is an absolutely acquired taste. Nobody likes soda naturally. Ever drink a warm Coca-Cola? It’s the most disgusting thing you’ve ever had in your mouth. I think you have to learn to like this stuff. I never did.

P: As a kid I did—I loved it. Not warm, though. Well chilled.

R: You shouldn’t let your soup get cold. It smells good.

P: And what about readers? Could you tell they were responding?

R: Our readers loved this stuff. That was the thing. In my second issue I think, we did a profile of Thomas Keller. This is like ’99. Would you like a deviled egg? It’s delicious.

P: Yeah, try some of this soup.

R: So there’s this scene where...have another egg...where Keller wanted to make rabbits and kill them himself. And he does a really inept job. He manages to break this rabbit’s leg as he’s trying to kill it and he says rabbits scream really loud. It’s gruesome. And we thought long and hard about whether we were going to put this in the story. And I said: “It’s going in because he concludes that if he’s alone in the kitchen and he’s finally killed this rabbit, it’s going to be the best rabbit anybody ever ate because he finally understood in that kitchen with this screaming rabbit that meat was life itself.” And I said there’s no way I’m leaving this out of the piece. So my publisher looks at this and goes crazy.

P: In my new book, I tell the story of my pet pig, Kosher. My dad gave her to me, and named her . Anyway, Kosher loved the smell of barbecue, and one day that summer she escaped her pen, made her way up the beach on Martha’s Vineyard, found a man grilling a steak on his deck and, like a commando, rushed the grill, topped it and ran off with the guy’s steak. Luckily for me the man had a sense of humor.

R: So what happened to Kosher?

P: Well, she grew and grew and grew. Toward the end of the summer I went to the state fair and entered Kosher and she won a blue ribbon.

R: For being best pig?

P: Best pig in its class, which was sow under one year—she was the only pig in her class. Wasn’t hard! But she was beautiful—an all-white Yorkshire pig. And at that fair I met James Taylor. I won “sow under one year” and he won for “sow over one year.” And he had a famous pig named Mona . So when the summer was over, I got in touch with him to see if he would board my pig for the winter.

R: So you’re 16?

P: I’m 16. Yeah.

R: That’s pretty bold at 16.

P: I had a crisis. We were going back to Manhattan at the end of August and my dad hadn’t thought that far ahead. We now had a 200-pound pig, so I had to deal with it before the end of the summer. Otherwise, this pig comes back to Park Avenue where we lived. The co-op board was not going to be happy.

R: Park Avenue Pig.

P: Right! So somehow I got in touch with James Taylor. And he said, “Yeah, I’ll take care of your pig. Bring it over.” And I drove over in my VW Squareback. And we put the two pigs in the same pen. And I didn’t know that mature pigs confronting a baby pig that’s not their own will harass it.

R: And he didn’t either, obviously.

P: No, he knew as little about pigs as I did. And his was 500 pounds. Most pigs are slaughtered before they reach full weight and we seldom see just how big they can get. So Mona is chasing Kosher around and around and it’s starting to get a little alarming, like, Kosher is sweating and stressed and what looked like working out their pecking order started to look a little different. So we decided we had to separate them. And James Taylor had just had an accident , had cut his hand seriously so he couldn’t use it. In fact, he canceled a tour as a result. So I had to build another pen, in the woods. Just putting some boards between four trees. And he tried to help me. And by the time we had that ready and went back to get Kosher, Kosher was dead. Mona had killed Kosher. Probably just given her a heart attack—I don’t know. There was no blood or anything. It was horrible, and he felt terrible. Here was this kid, this 16-year-old kid, and his pig had just killed the kid’s pig.

R: So did you eat Kosher?

P: No, I couldn’t. I might have made a different decision, now. But then, who knows what a heart attack does to the taste of the meat?

R: Adrenaline. She had been running around for a while, she probably didn’t taste too good.

P: Stress before slaughter, that’s where you get those “dark cutters,” as they’re called in beef production—that dark mushy meat you sometimes get from stressed-out animals. Instead I just dug a hole, right there, and we buried her with the blue ribbon, that I had hanging from the rearview mirror of my car...

R: You didn’t keep the ribbon?

P: No, I probably should have kept the ribbon.

R: That’s a very sad story. Your father took no responsibility for this at all?

P: He thought it was a cool idea, so he gave me the pig, and then I was on my own. I suppose it was a good lesson. I learned something about responsibility. And that pigs don’t make good pets. I mean Kosher was driving me crazy. Before that she was biting my sisters, escaping all the time.

R: That’s the interesting thing about meat-eating. At what point do you stop worrying about life?

P: Peter Singer, the animal liberationist, used to only eat any animal without a face. But then he stopped doing that, too.

R: People draw the lines in very different ways.

P: I think now I could raise a pig and kill a pig for food. I didn’t feel a sense of attachment. Clearly a pig is a very intelligent animal, but I think I could probably do that. I raised chickens, and worried that I wouldn’t be able to kill them, but by the time they were mature, I couldn’t wait to kill them. They were ruining my garden, abusing one another, making a tremendous mess. Meat birds are not like hens. Their brains have been bred right out of them, they’re really nasty and stupid. And every other critter for miles around was coming after them. I lost one to a raccoon, one to a fox, one to an owl—all in the course of a week. In the end I couldn’t wait to do the deed, because otherwise, somebody else was going to get the meat.

R: Around here, I know so many people raise chickens and at least half of them are going to the foxes.

P: Everyone loves chicken! [Laughter]

R: Want another deviled egg?

P: I’m good, I have a lot of food coming, thank you.

R: In your new book, Cooked, you said, “There’s nothing ceremonial about chopping vegetables on a kitchen counter.” I have to tell you, I so don’t agree with you. For me, chopping onions, putting them in butter, the smells coming up, that’s all totally sensual, totally seductive. And truly ceremonial, in the best way. I built a kitchen so that people can stand around and watch me cook.

P: To me onions are the metaphor for kitchen drudgery. Cutting them is hard to do well and they fight you the whole way. But I worked at this for a long time, learned everything I could about onions—why they make us cry, how to prevent it, why they’re such a huge part of cuisine worldwide, and what they contribute to a dish. I finally learned this important spiritual truth, which is bigger than onions: “When chopping onions, just chop onions.” When I finally got into the zen of cutting onions, I passed over to another place. Part of the resistance to kitchen work like chopping is a macho thing. Men like the big public deal of the grill, the ceremonies involving animals and fire, where women gravitate toward the plants and pots inside.

R: Chopping is like a meditation.

P: A zen practice, I agree. I learned that from my cooking teacher Samin Nosrat, who is a serious student of yoga. She talked to me about patience, presence and practice. She thought they applied equally well to cooking and yoga. And they do. They are very good words to keep in mind. I’m impatient, generally, dealing with the material world and she is someone who will sweat her onions longer than anyone I have ever seen and they do get so much better. The recipe says 10 minutes, she thinks “no, we’re doing 45.” And it definitely is better.

R: All recipes are sped up, because now that we put times on them...

P: Exactly.

R: At Gourmet, you tell someone it’s going to take an hour and a half to make a dish...

P: ...and they wouldn’t read it! I know. I was looking at some recipes today and it was “No, nope, no...oh, 20 minutes? OK.” It’s a real problem. You spend an hour on lots of things and don’t begrudge the investment of time, the way you begrudge it cooking. We often feel like we should be doing something else, something more important. I think it’s a big problem with getting people to cook.

R: What’s your favorite thing? What do you most like cooking?

P: I love making a braise. I love brown- ing meat, the whole syntax of doing the onions or the mirepoix, and figuring out what liquid you’re going to use. It’s so simple and such a magical transformation. And I love how it tastes.

The food is delivered to the table.

R: I love everything in a kitchen—even doing the dishes. But the part of your book I found most fascinating is the section on fermented food. I’m fascinated by the pickling people.

P: That is fun. There’s so much fervor around pickling, a lot of people getting really good at it, really good artisanal picklers.

R: It’s amazing, too, such a change from “oh, pickling just means pouring some vinegar over something,” to “pickling means fermentation.

P: Right, lactic acid fermentation. There are a lot of picklers still around that don’t get that distinction at all. But in my journey into cooking I had the most fun when I got to the microbiology of fermentation, learning that you could cook without any heat using micro-organisms—this is kind of mind-blowing. It’s a totally different kind of cooking—your control is partial, at best. Fermentation is “nature imperfectly mastered,” as one of my teachers put it to me. These cultures, they have a life of their own. In a way, it’s like gardening. I think that’s one of the reasons I responded to it. It engages you in a conversation with nature, with other species. You can’t call all the shots.

R: You’re calling all these microbes to you.

P: Yes, you’re trying to create conditions that will make them happy. There’s so much mystery because they’re invisible. I bake with Chad Robertson in San Francisco, who I think is the best baker in the country. I made a point to shake his hand as many times as I could when I was building my starter. I figured, “I want some of his bugs. He has a fantastic starter.” I could have asked him for it, I suppose, but I was worried that might be a bit too forward, to ask somebody for a little of their starter. I don’t know whether he would have given it to me.

R: That’s an interesting thing.

P: I don’t know what the etiquette is around starters. But most bakers don’t share them. They feel their starter is part of their identity. He is less mystical about his starter than a lot of bakers, though, because he’s lost it a few times and was able to restart it pretty easily.

R: Well, he’s in San Francisco, which is like “ground zero” for those folks.

P: Actually that’s a little bit of a myth. Everybody thought that the reason for San Francisco’s sourdoughs was this one particular microbe that was discovered in the ’70s. Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis is the name it was eventually given .

R: I know it, the first article I ever did, was on “unique San Francisco foods” in, I don’t know, 1977?

P: That’s very soon after this research was done. Since then, however, it’s been found all over the world. It’s in Belgium, it’s in Moscow. Nobody really understands it because it’s not found anywhere except in sourdough starter—their habitat is in sourdough starter and nothing else. They can’t find it on the wheat, they can’t find it on the body. There’s some way they get conveyed from one to the other but they haven’t figured it out yet.

R: Are people working on it?

P: There is a new sequencing technology that makes it possible to take any sample of biomass and figure out exactly what’s in it. Presumably, scientists will discover where L. sanfranciscensis comes from and how it gets around, but they haven’t yet. They have a saying in microbiology: “Everything is everywhere, but the environment selects.” So if you create the right conditions, there are so many bacteria everywhere, at all times—in the air, on your skin, everywhere—that they will find it and colonize the habitat. I went really deep down the rabbit hole of microbiology in food and in our bodies, because there are real links between the fermentation that takes place in a pickling jar or cheese, and the fermentation taking place in your body. They are not the same, but they have similarities and one affects the other.

So, for example, the orange bacteria in a washed rind cheese, Brevibacterium linens or B. linens, are very similar to the ones on your body and specifically in your armpits, that creates the human smell by, in effect, fermenting our sweat. There’s a reason why it appeals to us and why at the same time we find it disgusting.

R: It smells like sweat.

P: Old sweat. It’s on that edge, I talk in Cooked about the erotics of disgust, which is a real element in the appeal of strong cheeses, and in other fermented foods. It turns out that almost every culture has a food that other cultures regard as disgusting. You talk to an Asian about cheese and they are completely grossed out.

R: On the other hand, talk to an American about natto .

P: Or stinky tofu! In China, they think that is such a “clean” taste. No, to me it smells like garbage.

R: It’s like trying to understand sex. Who can understand it?

P: I know. But it’s fun to try.

R: But it’s completely...you feel like it’s your dinosaur self.

P: This stuff is. Smell is really deep.

R: No way you can understand this with your mind. The whole pleasure/pain, disgusting/exciting...

P: The interesting thing too is that cheesemakers don’t have a vocabulary to talk about this. You can understand why, if you’re selling food, you don’t want to talk about disgust. I found a couple people in that world who were really articulate, though particularly this eccentric guy in France named Jim Stillwaggon. An American in France, a cheesemaker and a philosopher. He had a website called “Cheese, Sex, Death and Madness,” which is really out there. He’s crazy and fearless in writing about that frontier between attraction and repulsion.

R: Where is he?

P: He’s in France. But the website, last time I checked, the link was broken. I write about it in the book. I heard about him from Sister Noëlla, the cheesemaker in Connecticut. [She has now passed along cheesemaking duties to others in the abbey.] She was willing to go there with me and talk about these issues. Which is really interesting. She believes cheese should be added to the Eucharist, that it’s an even better symbol than bread because it reminds us of our mortality. I hope she doesn’t get in trouble with the pope for this heresy!

Laughter.

R: The last pope, maybe. This one, it’s probably OK.

P: Of all the byways I went down, that one was perhaps the most fun. There’s a great psychological and philosophical literature around disgust. Do you know Paul Rozin, do you know his work? He’s a psychologist at Penn who studies our unconscious attitudes toward food [see “Accounting for Taste,” p. 60]. He’s very entertaining on the subject.

R: Yeah, he’s a fascinating guy, a psychology professor who focuses on taste. I had a really interesting on-stage discussion with him last year at the Rubin Museum of Art. We were talking about food and memory, which quickly got into pain and pleasure around food. I think we could have gone on talking all night.

P: This pork is really good, I’m going to give you a piece.

R: The chicken is also good, do you want a piece? I assume you’d rather have dark meat than white meat?

P: Yes. Thank you. There’s a cool little riff in the new book about seaweed. The Japanese have a gene in one of the common gut bacteria that the rest of us don’t have that allows them to digest seaweed. It was just recently discovered. As often is the case, foods carry on them the microbes adapted to break them down—they are just waiting for them to die. It’s the same thing that makes the sauerkraut go—there’s a lactobacillus on every cabbage leaf waiting for it to bruise. Anyway, there was a marine bacteria, I forget the name of it, that was found with seaweed and the Japanese were exposed to enough of it, over enough years, that the gut bacteria acquired a gene from it, which is something bacteria do. They just pick up genes, as they need them, like tools. This one got into the Japanese microbiome and now allows them to digest seaweed, which most of us can’t do.

I thought well, we’d be getting it pretty soon, but in fact we won’t. They didn’t used to toast their seaweed. We toast ours; it’s been cooked and sterilized, so we’re killing the bacteria.

R: At a good sushi bar in Japan, they would run it over a flame. They will do it until they crisp it, so when you get it, it has that really crisp sheet of seaweed, the warmth laid around the soft rice.

P: They must have, for many years, eaten it raw. They may have been eating seaweed in other dishes, too. It’s in soup.

R: So we can’t metabolize it?

P: Nope. We get nothing from it except the taste on the tongue. It’s a shame, isn’t it, because I love seaweed. Anyway, the science kind of absorbed me in this project.

R: Where did you learn it?

P: I talked to a lot of microbiologists at [UC] Davis who work on sauerkraut and other fermented foods, trying to figure out how it happens and what it does for our bodies. It’s a succession like any other ecosystem. One species starts the fermentation and it’s fairly acid-tolerant, and it acidifies the environment to a certain extent. Then another microbe, more acid tolerant, comes along and so on until you get to L. plantarum, which is the acid-loving oak of the sauerkraut ecosystem, the climax species. And then it’s done.

One woman in the large group at the next table stops by on her way out to say how much Michael means to her. Her book group meets monthly at Bell & Anchor; she proudly proclaims that The Omnivore’s Dilemma is required reading at her son’s high school. Michael looks slightly pained.

P: I feel like [my book] has been inflicted on a lot of kids.

R: What are you going to do next?

P: I just wrote a story on the microbiome. I had my body sequenced, so I know what bacteria I’m carrying, what do they mean for my well-being, what do we know, what do we not know. I’ve been amazed to learn all of the links between microbial health and our general health. This all started by trying to understand fermentation. The fermentation outside your body, and its relation to the fermentation inside your body. The key to health is fermentation, it turns out.

R: Really?

P: It’s very possible that the master key to unlocking chronic disease will turn out to be the health and composition of the microbiota in your gut. But we’ve abused this ecological community—with antibiotics, with our diet, with too much “good” sanitation.

Waitress: Sorry to interrupt. Would you like dessert?

P: I’m very happy watching my companion have dessert.

R: I’ll have the yogurt lemon mousse. Unless you think I should have something ?

Waitress: You’ll like the lemon.

R: I’m a lemon person.

P: I am too. I just downloaded that recipe for that lemon soup from your website. How do you pronounce it?

R: Avgolemeno.

P: Yeah, I got to try it. I have an oversupply of Meyer lemons, as you know happens in Berkeley.

R: Oh, I am not a Meyer lemon person.

P: You’re not? You don’t like Meyer lemons? Not tart enough?

R: No. They’re, you know, a lemon crossed with an orange . Why would you want to do that? I like acid.

P: So what kind of lemons do you like? Conventional lemons? As sour as you can stand ’em, right?

R: You know, lemons from Sorrento are really good. I also feel that way about onions now. It’s so hard to get an onion that still makes you cry.

P: Everything is trending toward sweetness.

R: They’re muted. I hate the fact that everyone loves Meyer lemons. I just hate it.

In the end Michael ate half my dessert. We finished the wine. And then, reluctantly, we got up to leave; we both had a long drive ahead of us. Walking out we were stopped by a group of young butchers sitting at the bar discussing the morality of meat. Owner Mark Firth came over to join the conversation and talk proudly of his pigs. It was 2013, in a rural Massachusetts town, and I had a moment of pure joy. In 1970, when I first became concerned about the future of food, I could not have imagined this moment. Even as recently as 2006, when Michael came out with The Omnivore’s Dilemma, it would have been foolhardy to hope that this could come to pass.

We looked at each other. We smiled.