With “Master of None,” Aziz Ansari Has Created a True American Original

The star of the breakout television series brings the voice of his generation to the masses

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/c9/99c90579-af86-440c-8dfa-c27e44a6b667/dec2016_d05_ingenuity-wr.jpg)

Aziz Ansari calls 15 minutes before our scheduled interview. “Hey, it’s Aziz,” he says cheerily, as though he’s a friend and not the celebrated comedian, actor and writer who created a new American original in the form of Dev Shah, the character he plays in his groundbreaking Netflix show, “Master of None.”

Aziz—since we’re on a first-name basis—explains that he has an unexpected window of time and wonders whether we might talk now. Sure, I say, and pause the episode of “Master of None” I’ve been watching, in which Dev is sitting in a restaurant with his buddies Brian, Arnold and Denise, wondering why he hasn’t heard back from a woman he asked out on a date.

There are a lot of obvious parallels between Dev, a 30-something actor living in Brooklyn, and Aziz, 33, who as we speak is leaving his own Brooklyn apartment and heading to the office. Like Aziz, who grew up in Bennettsville, South Carolina, Dev is the American-born son of Indian immigrants, grappling with his identity and the ways in which his life, while infinitely easier than his parents’ lives, is so complicated. “He’s trying to figure it out,” says Aziz. “You know, I’m in my 30s, I’m an adult, but what am I doing? What am I doing in my relationship? Is this the career I want? Is this who I want to be?”

Unlike Dev, whose career highlight thus far has been a Go-Gurt commercial, Aziz has been ascendant ever since he started performing stand-up at open-mike nights while studying marketing at New York University. “When I first did it, I was like, ‘Oh God, I really like this, and I want to get really really good at this,’” he says. He did, and ended up selling out Madison Square Garden in 2014.

He also began landing roles in movies and on TV, the most famous of which is probably Tom Haverford, the would-be Lothario and business mogul in NBC’s “Parks and Recreation.”

It was there that he met Alan Yang, a writer and producer on the show. “We’re both the children of immigrants, raised not in big cities, our dads were both doctors, we worked hard in school,” says Yang, whose parents are from Taiwan. Together, they began developing the idea for “Master of None.”

“We were just thinking it would be like a hangout show, à la ‘Seinfeld,’” he says. “Let’s make it funny, let’s make it entertaining, and on the level that we would have with our friends. I didn’t go into the show assuming it would be some kind of political statement.”

But as Ansari points out, simply having a nonwhite in the lead role was a kind of statement: “Normally people like myself, I’m the friend of some white guy, you see him go on his adventure, and I say something funny and go away. But in ‘Master of None’ the story is really about me, and I’m given the agency of like, a normal protagonist.”

As this idea sank in, the creators recognized they had a unique opportunity to do something more ambitious. “We kind of realized, we get to do what we want,” Yang says. “So why not challenge ourselves and do something that no one has ever seen before?”

Out of this came the show’s unusual format: single-themed episodes that pair conventional sitcom laughs with more thoughtful subjects. “Parents,” in which Dev and his friend Brian learn their parents’ back stories, draws on the Ansari and Yang family histories (and features Ansari’s actual parents playing Dev’s). “What an insane journey,” says Brian at the end. “My dad used to bathe in a river, and now he drives a car that talks to him.”

Then there’s “Indians on TV,” in which Dev confronts a racist TV executive and receives salient advice from the rapper Busta Rhymes. “I don’t think you should play the race card,” he tells him. “Charge it to the race card.”

Although Yang and Ansari won an Emmy for their writing on “Master of None,” this is probably the closest thing the series offers in the way of a catchphrase, like Tom Haverford’s “Treat yo self!,” which people yelled at Ansari on the street for years.

“After we were done [with the first season], I was like, ‘What are people going to yell at me?’” he says. “Instead, they want to come up and have these like, emotional conversations” about the ways the show mirrors their lives. “People are like, ‘Whoa, that’s my parents’ story.’ Or, ‘Whoa, I had a fight like that with my girlfriend.’”

Which is exactly what the series is after. “I try to get deep and go into the personal stuff because I really believe that’s the most universal,” says Ansari, who acknowledges that in addition to mining their own lives, he and Yang have occasionally pilfered the experiences of people they’re close to.

“There’s a quote from, I think, Quentin Tarantino, about how if you’re not scared to show your friends and family your scripts, then you aren’t being hard enough on your writing. And I am terrified to show people my stuff sometimes.”

Then he apologizes: “You know, I am so sorry, I didn’t charge my phone last night and it’s about to die. Can I charge and call you back?”

Sure, I say to my pal Aziz. No problem. So I hang up. Minutes tick by. Then hours. When my husband comes home from work, I’m pacing. “Aziz Ansari was supposed to call me back and he hasn’t,” I say.

“Did you say something to offend him?” he asks.

“No!” I say. “I mean, I don’t think so.”

I’m worried, but there’s also something about the situation that feels familiar. While I’m waiting, I turn my TV back on, to the “Master of None” episode I’d been watching before Ansari called.

“Maybe she’s busy,” Arnold says of the woman Dev hasn’t heard from.

“Nah, I just checked her Instagram,” Dev replies, holding up his iPhone. “She posted a photo of herself popping bubble wrap. Caption: ‘I love bubble wrap.’”

“Maybe she’s really nervous,” Dev says.

“No,” Denise insists. “She doesn’t like you.”

This doesn’t bode well. Eventually, Ansari does call back, and explains he was pulled into a table read. He is apologetic but also cracking up: “I was like, She’s gonna think I heard her say something awful and was like, ‘Oh, my phone died! Gotta go, bye!’”

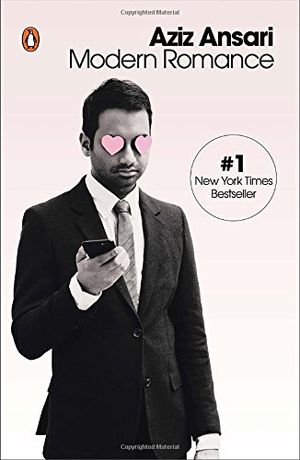

As it turns out, he’s been there. The scene I’d been watching was based on a situation Ansari wrote about in Modern Romance, the best-selling book he published last year with sociologist Eric Klinenberg, in which he described the “tornado of panic and hurt and anger” he felt after texting a woman he was interested in and getting nothing in return. In the book, he wrote that when he talked about it in his stand-up routine, he found that doing so was therapeutic, not just for himself, but perhaps for the audience as well. “I got laughs, but also something bigger,” he wrote. “Like the audience and I were connecting on a deeper level.”

This kind of deeper connection is what “Master of None” strives for, and what distinguishes it from shows like “Seinfeld,” which was hilarious and observant about the foibles of modern life but whose protagonists were so hollow, they were ultimately sent to prison for being one-dimensional. Not so the characters on “Master of None,” who appear to be making a sincere effort to figure it out. In the last episode of the first season, Dev, having scrapped a romance that was comfortable but losing steam, gets on a plane to Italy to learn how to make pasta and, he hopes, to find himself.

Aziz Ansari did pretty much the same thing. “I put my whole head into Season 1, and after that I just needed a few months off to live my life and be a person,” he says. He spent a few months hanging around Italy, eating pasta alla gricia—a photograph of the dish is affixed to Dev’s refrigerator—and watching old movies. “It’s funny, because it’s all the same fears and anxieties,” he says. “Everyone is talking about the same [stuff], in a way, whether it’s not hearing back on a text or someone not calling you back. You listen to old songs, you listen to old music, and you are like, ‘Oh, these fears are really universal and generations of people have had them before me.’”

Whether Dev will figure it all out is an open question: Viewers will have to wait until April, when Netflix releases Season 2, to find out. “We’re being even more ambitious, trying weirder stuff,” says Aziz Ansari, who in contrast to Dev Shah, knows exactly what he is doing. “I have a lot of stories and ideas that I want to share,” he says. “And I want to get better at executing them and becoming a better writer, director, actor. Really, I just want to keep making stuff.”

Modern Romance