The Most Irish Town in America Was Built on Seaweed

After discovering ‘Irish moss’ in coastal waters, Irish immigrants launched a booming mossing industry in Scituate, Massachusetts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/71/a6/71a61d66-ec9e-4deb-855c-0ac760cfc335/scituate_harbor.jpg)

A lot of us start our days with seaweed, whether or not we know it. From toothpaste to moisturizer to yogurt, a compound derived from seaweed called carrageenan is responsible for adding smoothness and suspension to some of our favorite products. Now a global industry, carrageenan production in the United States had its unlikely beginnings over 150 years ago when an Irish immigrant spotted a familiar plant off the side of his sailboat. Although most of today’s carrageenan-containing seaweeds come from China and Southeast Asia, this discovery leaves behind a legacy in what is claimed to be the most Irish town in America.

Around 1847, Daniel Ward was sailing off the coast of Boston when he spotted gold—at least in seaweed form. An immigrant from Ireland, Ward had been working as a fisherman when he saw red algae beneath the ocean surface that he recognized as carrageen, or Irish moss. Back home in Ireland, the Irish harvested this seaweed for uses like making pudding and clarifying beer. Ward immediately saw an opportunity to tap into this unknown resource in his new country, and soon abandoned fishing to settle on the beaches of a small coastal town called Scituate, midway between Boston and Plymouth.

Prior to Ward’s arrival, Scituate was unpopulated by the Irish. This proved to be an advantage, since the locals—mostly farmers and fishermen—had no interest in Irish moss and thus welcomed Ward and his friend, Miles O’Brian, and their entrepreneurial endeavor. As Ward began building the industry, Irish immigrants fleeing the Potato Famine from 1845 to 1849 caught word about the opportunity overseas and came to Scituate to take part in this growing business. “By 1870 there were close to 100 Irish families... [and] by the early 1900s other Irish families that maybe weren’t harvesting the moss, but had relatives that were, knew about the town and moved here,” says Dave Ball, president of the Scituate Historical Society. “You can trace the roots of the whole influx back to Irish mossing.”

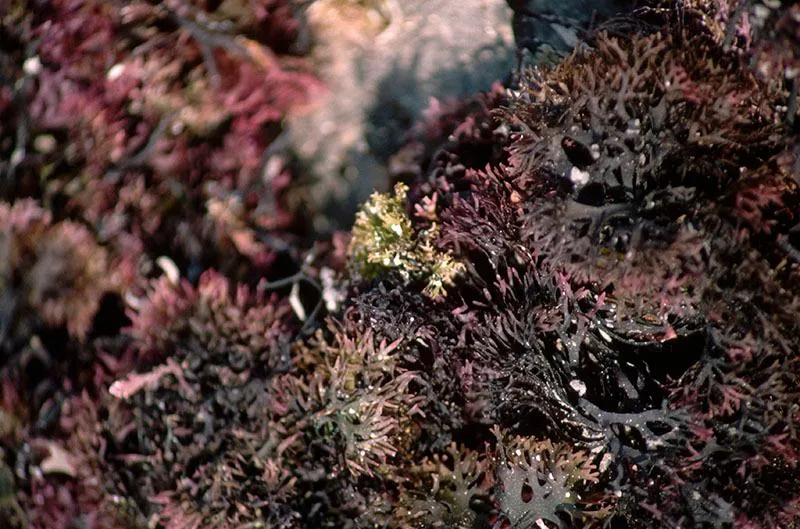

Irish moss, formally known as Chondrus crispus, grows on the surface of undersea rock formations. Harvesting is traditionally done by hand, using a 12-foot rake to pry off the broccoli-like tops of the moss, being sure not to rip out the stems or “holdfasts,” which would prevent the plant from growing back. Mossers tended to travel alone on their 16-foot dories, usually for two hours before and after low tide so that the water is shallow enough to scope out algal prospects.

Proper preparation of Irish moss is just as critical as its harvesting. During Ward’s time, mossers dried their harvests on the beaches, a process that took several days with the help of their wives and children. “It was a family affair,” says Ball. Weather was also a game-changing factor. Fresh water breaks down Irish moss in a process known as bleeding, turning it to a useless mush. “If it was going to rain, they would have to put the moss in a pile and cover it with a tarp,” explains Ball. “That would be the responsibility of the kids and wives.”

Once dried, Irish moss was sold to companies for a variety of uses. The moss was first boiled and broken down in fresh water, and then turned into a white powder through alcohol treatments and drying. At the time Ward started his business, carrageen was already recognized as a useful emulsifying and suspending agent. For instance, an 1847 patent in England claimed a carrageen gelatin for manufacturing capsules, while an 1855 patent from Massachusetts suggested using Irish moss to coat wool prior to carding in order to loosen the fibers and reduce static electricity. The latter cited that Irish moss was an ideal candidate due to “the abundance and cheapness of the material, it being an almost worthless product on most parts of our sea-coast.”

The seasonal conditions of mossing also paved the way for a new occupation: lifesaving. Harsh New England winters could destroy incoming boats, and crews often died from hypothermia. In 1871, the United States Lifesaving Service was formed to rescue these shipwrecked sailors. Since the peak season for mossing runs from June through September, mossers were free to join the Lifesaving Service as “surfmen” during the perilous winter months, allowing them to save lives along with their paychecks.

During World War II, the mossing industry boomed, also spreading into Canada. In just one year, the Canadian production of Irish moss rose from 261,000 pounds (dry weight) in 1941 to over 2 million pounds by 1942. Agar, a competitive gel product that was predominantly made in Japan, had been cut off as a result of the conflict. This gap allowed carrageen moss to take center stage. By 1949, there were five American companies that produced the purified Irish moss extractive, including the Krim-Ko Corporation in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and Kraft Foods Company in Chicago.

Thanks to widespread manufacturing, Irish moss found a whole slew of new applications, such as stabilizing chocolate milk and being combined with ascorbic acid to form a preservative film over frozen foods. “Many more useful properties are still waiting to be explored,” wrote a chief chemist from Krim-Ko in a 1949 report in Economic Botany. “It is the attainment of this phase of application research that insures Irish moss its position as a raw material for an American industry.”

The war also changed perceptions of who a mosser could be. Prior to World War II, women rarely mossed on their own boats, instead sticking to the shores to collect remnants that had washed up. The one notable exception was Mim Flynn, the “Irish Mossing Queen”, who rowed her own mossing dory in 1934 at just nine years old as a way to make money during the Depression. Standing at only 5’2”, Flynn became a sensation and was covered by newspapers as far as Canada. “She was written up everywhere,” says her daughter Mary Jenkins, whose father came from the MacDonald family, early mossers who moved to Scituate in 1863. “But that’s what fascinated people—you know, here’s this little sprite out there mossing and making a business out of it.”

Although her mother was a socialite who didn’t approve of mossing, Flynn started a trend that expanded during the war. “I think one of the things that got women more involved was the number of articles being written about my mother, because she was so young,” says Jenkins. “And then World War II happened, and there was even more reason to try and figure out different ways of bringing an income in.” While most working men were serving overseas, women picked up the rakes and began hauling harvests of their own.

Mossing in Scituate continued to provide jobs well through the 1960s under Lucien Rousseau, a local buyer and “Scituate’s last Irish moss king.” Hawk Hickman, who mossed for over 30 years and has written two books on the subject, recalls his days on the ocean after Rousseau provided him with a boat and a rake. “You worked for yourself,” he reminisces. “The harder you worked, the more you made. You had fabulous comradery with all of your buddies you went out with, you had the best tan of anybody in town… You were part of a 130-year-old tradition.”

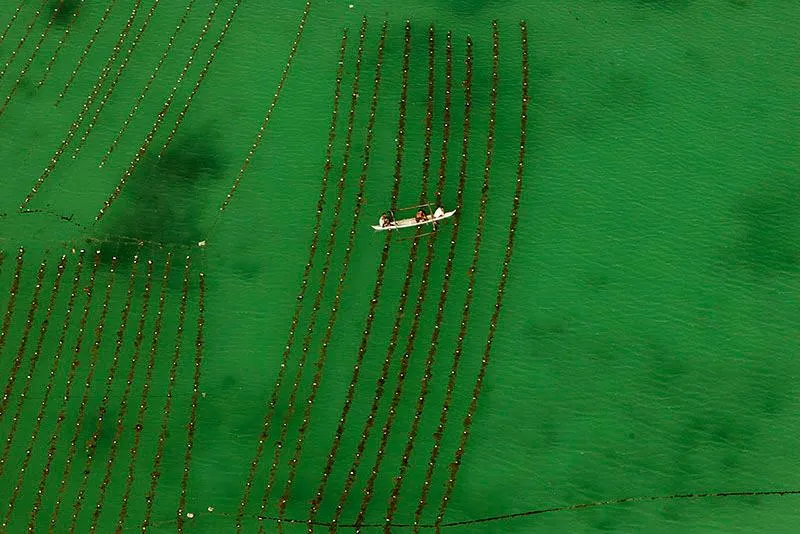

Over the next 30 years, the price of moss rose from 1.75 cents per pound in 1960 to over 10 cents per pound by 1990. But beneath this success, the game was quietly changing. Mechanical dryers (“Think of oversized clotheshangers,” says Ball) were introduced; smaller companies merged to form larger ones; and, according to Hickman, “more and more youngsters got motors instead of rowing out every day.” Most significantly, large companies started to look for cheaper sources of carrageenan, like seaweed farms that were popping up in the Philippines and other parts of Southeast Asia.

Suddenly, around 1997, Irish mossing in Scituate ended as abruptly as it had started. “Lucien died [in the early 1980s] for one thing,” explains Hickman, “and there was no one readily available to take his place because he was sort of a unique person who could fix any kind of machinery and keep things going.” Another family briefly took over the business, but Ball says that they ran into problems with their mechanical driers and couldn’t recover. “They told the mossers to go home,” he recalls. “And that was the end of it.”

In this way, the rise and fall of Irish mossing in Scituate echoes the fates of so many other cottage industries in America. Hickman compares it to blacksmithing. “Like many manual industries, there were a combination of factors that led to its demise—foreign competition, people unwilling to do it anymore,” he claims. “If you look at the horseshoeing industry, when we switched over from horses and carriages to cars, gradually most of the blacksmiths disappeared, [except] a few that specialized in it just for the people who were going to have horses as a hobby.”

Neither Hickman nor Ball think a return to Irish mossing in Scituate is likely, citing a combination of factors, including today’s safety regulations and seafront properties taking up any potential drying space. “The new yuppie wealthy people would start hollering about seaweed on the beach,” jokes Hickman.

But even without a daily fleet of mossers, the effects of the industry are still palpable throughout Scituate. According to Ball, the 2010 census showed that Scituate had the highest number of people claiming Irish ancestry than any other town in America, almost 50 percent of its roughly 18,000 residents, earning it the nickname the “Irish Riviera.” Ball also manages Scituate’s Maritime and Mossing Museum, which opened two weeks after the mossing industry officially ended in 1997. Once a year, every third grade public school student in Scituate visits the museum to learn about the town’s nautical history, including the contributions of Irish mossing and the characters behind it.

The museum also hosts Irish mosser reunions, where veteran mossers come back to share stories and hear about the industry today. Hickman even brings his old dory to complete the experience. On a graffiti wall inside the museum, mossers can write their name and their record harvest for a single day. “Some of them lie about it, of course,” Ball tells me.

While Scituate has since found other industries and college students now look elsewhere for summer jobs, Irish mossing undoubtedly leaves behind memories of its salt-crusted Golden Age. “Some people I mossed with went on to high profile careers,” says Ball, “and they would still tell you the best job they ever had was mossing.”