The Nerf Football Has Been Inspiring Backyard Championships Since 1972

Former Minnesota Vikings kicker Fred Cox invented the safer, softer football for kids of all ages

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/af/7aaffefb-f2e4-4789-954e-7abd7b658666/nerf_football.jpg)

Undoubtedly, Jimmy Garoppolo and Patrick Mahomes will meet countless times in imaginary games before and after Super Bowl LIV. Many young—and even not-so-young— fans will head out to the backyard to challenge each other, pretending to be the quarterbacks of the top two teams in football.

And, just as likely, the ball they will be tossing around during that championship matchup will be made of foam. Introduced in 1972, the Nerf football has been a mainstay of gridiron challenges for kids of all ages.

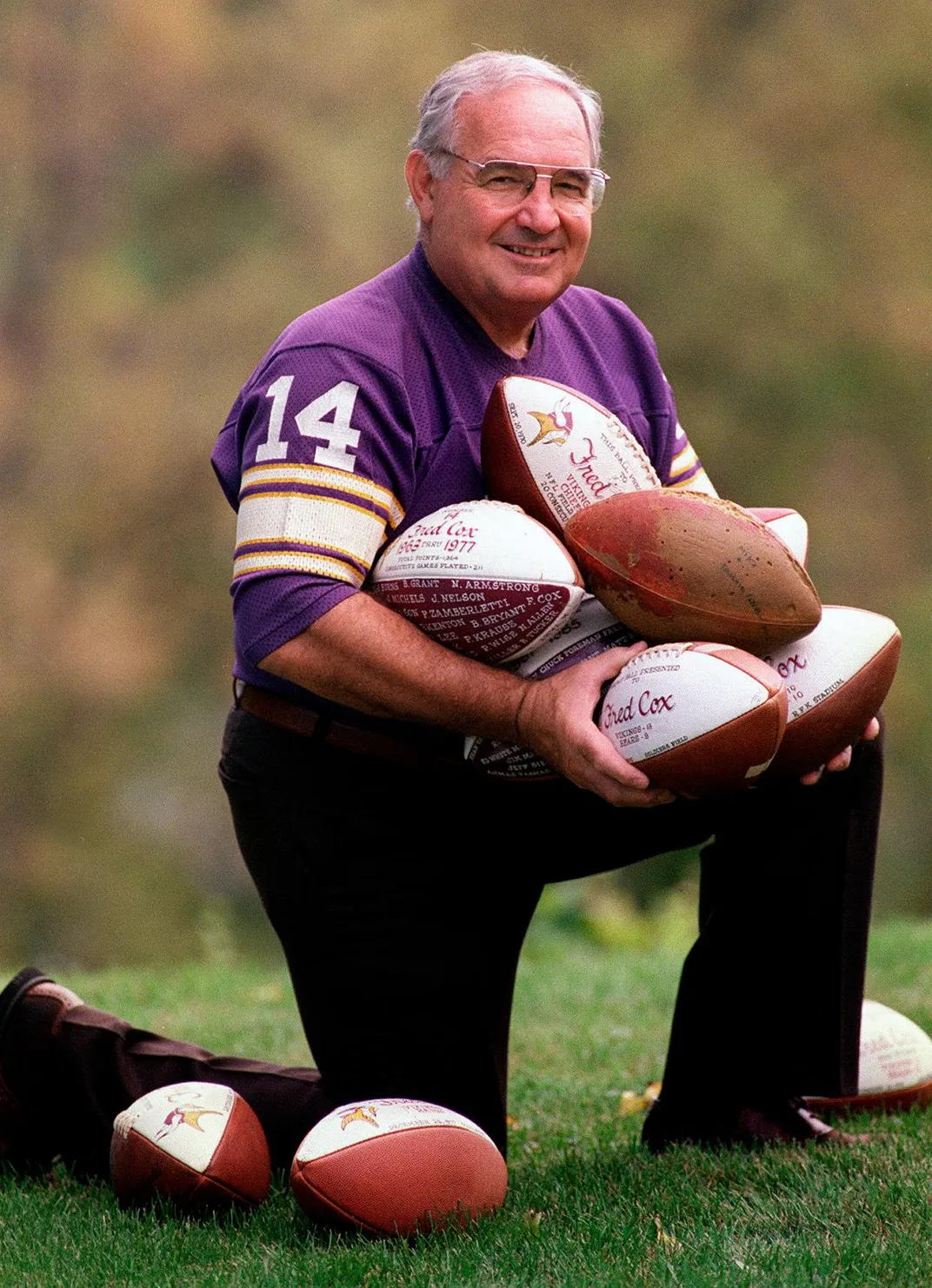

You can thank Fred Cox for that. The former Minnesota Vikings field-goal kicker, who died last fall, invented the smaller, softer football that was safer to use since it didn’t strain young arms and legs. Annual sales peaked at 8 million in 1979, but the toy continues to be a popular seller today.

“The Nerf Football is the equivalent of the Wiffle Ball,” says Christopher Bensch, vice president of collections at The Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, New York. “It’s safer and easier to use and perfect for confined backyards.”

The inventor was a popular player with the Minnesota Vikings from 1963 to 1977. Cox was an All-Pro kicker and led the National Football League in scoring twice. He kicked nine points in the final NFL Championship game in 1969 and played in four Super Bowls. When Cox retired, he was the league’s second all-time leading scorer. He still holds the record for most points scored by a Vikings player.

An all-around athlete, Cox played offense, defense and special teams before a back injury forced him to focus on field-goal kicking. He was a star soccer player in high school in Monongahela, Pennsylvania, and able to put his kicking skills to good use in football. Cox enjoyed his career with the Minnesota Vikings, but recognized the importance of the Nerf football to his family’s welfare. He was still earning as much as $200,000 annually nearly 50 years after the product was released. “He was proud of his invention,” says Wayne Stewart, a sports author who interviewed Cox for his book America’s Football Factory: Western Pennsylvania’s Cradle of Quarterbacks from Johnny Unitas to Joe Montana. “He retired at age 50 because of the Nerf royalties.”

However, the Nerf football was nearly the invention that wasn’t. Cox got the idea when talking with a fan who wanted to create a toy with plastic field-goal posts for kids to practice kicking footballs. However, when the man showed up at his home in Edina, Minnesota, Cox almost didn’t let him in the door because it sounded like a harebrained scheme. Fortunately, he didn’t act on his initial inclination.

Instead, Cox invited John Mattox into his home and listened to his pitch. The idea involved plastic goal posts with adjustable crossbars that kids could set up in their backyard.

“After hearing about the goalpost, I asked what kind of ball he was going to use,” he said in a 1989 interview with the Pittsburgh Press. “He said something heavy so the kids couldn’t kick it out of the yard. My response was that it should be something light so the kids wouldn’t hurt themselves.”

So there wouldn’t be “a bunch of sore-legged kids,” Cox suggested they make a smaller football out of foam. A local injection molder made the prototype, which had a thick skin as a result of the heat-based process. That feature gave the ball durability and grip when holding it, which proved to be a stroke of genius.

“No, it was dumb luck,” Cox would later say.

The partners took their idea to Parker Brothers, the toy and game manufacturer that had introduced the Nerf ball in 1969. The soft foam toy was designed for children to play with indoors without knocking over lamps or breaking vases. The company had tried to make a foam football by cutting it out of foam, which did not give it the grippable surface that Cox and Mattox had developed.

Parker Brothers was only interested in the ball, not the goal posts. That latter idea never took off, but the Nerf football sure did. Sales soared higher than a NFL record 64-yard field goal kick. Kids, college students and adults all wanted to try the new toy that fit easily in the hand and was fun to play with.

Parker Brothers initially marketed the product as “the official football of the NFL” with an asterisk. The small type at the bottom of the ad read: “That’s the Nerf Football League … not the National Football League, of course.” Other ads featured John Elway of the Denver Broncos, who claimed to have a record throw of a Nerf football, as well as the Manning boys—brothers Peyton and Eli with their father Archie, all of whom played professional football.

The success of the brand led to numerous extensions, including the far-flying Vortex, the boomerang-like Turbo Blast-Back, the whistling Gyro Vortex, the even-easier-to-hold Pro Grip, the complete-with-pass-routes Big Play and other variations. Parker Brothers was eventually acquired by Hasbro, which continues to make Nerf football today.

The toy had a profound effect on many NFL stars over nearly five decades. Many players, who were surprised to learn Cox had invented the Nerf football, fondly remember playing with it when young. “This was a big part of my childhood,” recalled Barry Sanders, a Pro Football Hall of Fame running back.

Platitudes poured out for Cox when he died last November at age 80. Many people in the Minnesota Vikings organization remembered him as a talented teammate, dedicated family man and kindhearted friend. Hall of Fame quarterback Fran Tarkenton recalled Cox’s intelligence, business acumen and ingenuity.

“He had a great brain and was a great thinker,” he said. “Fred was a great businessman and invented the Nerf football. He was an intellect that I spent every morning with before we played a game. I spent more time with him than any other player. Fred was a special, special human being who will be missed.”

Especially by generations of Nerf football fans.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)