A New Project Hopes to Give Transgender Americans Some Much-Needed Haircuts

To promote mental health during the pandemic, the Trans Clippers Project has provided hundreds of trans and nonbinary people with a free pair of clippers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/44/0e44735d-8a60-4220-a562-0cc9b72d289b/trans_clippers_project-main.jpg)

On a hot day in early April, Klie Kliebert was scrolling through a Facebook group dedicated to mutual aid in their New Orleans area. Most of the posts were nothing out of the ordinary, ranging from requests for housing to offerings of free food and COVID-19 masks. But then Kliebert came across something different: a message from a transgender individual asking for a haircut. With the city in the midst of a pandemic, some group members were confused about the request, while others commented that asking for a haircut was selfish and could put others at risk.

But Kliebert, co-founder of Imagine Water Works, an organization focused on climate justice, understood the need immediately. “As a trans person, I know what this is about,” says Kliebert, who uses the pronouns they/them. “It’s more than just a haircut.” Like the person who posted on Facebook, Kliebert keeps their hair short as an expression of their gender identity, and knows how deeply uncomfortable it is when their hair starts to grow too long.

For transgender and nonbinary people (meaning their gender identity does not fit into “male” or “female”), having access to hair clippers is about much more than looking good. Many experience gender dysphoria, or distress due to the conflict between their physical appearance and internal gender identity, which is exacerbated when a person can’t control how they look. “Being able to present in a way that feels congruent with your own internal gender identity is important,” says Morgan Ainsley Peterson, a licensed professional counselor in Pennsylvania who works with queer and transgender patients.

Many individuals also worry about being “clocked,” or recognized as trans while out in public, which can lead to an increased risk of harassment and violence. Having something as simple as hair clippers can greatly reduce this risk, therefore lessening a good deal of mental health struggles, Peterson says.

Yet, getting a pair of hair clippers isn’t always easy. In the United States, trans individuals are around two times more likely to live in poverty and three times more likely to experience unemployment—disparities that will hopefully be mitigated by the recent Supreme Court ruling that protects gay and transgender workers from workplace discrimination. And with COVID-19 keeping many people housebound, a lot of products, including hair clippers, are hard to come by due to increased demand.

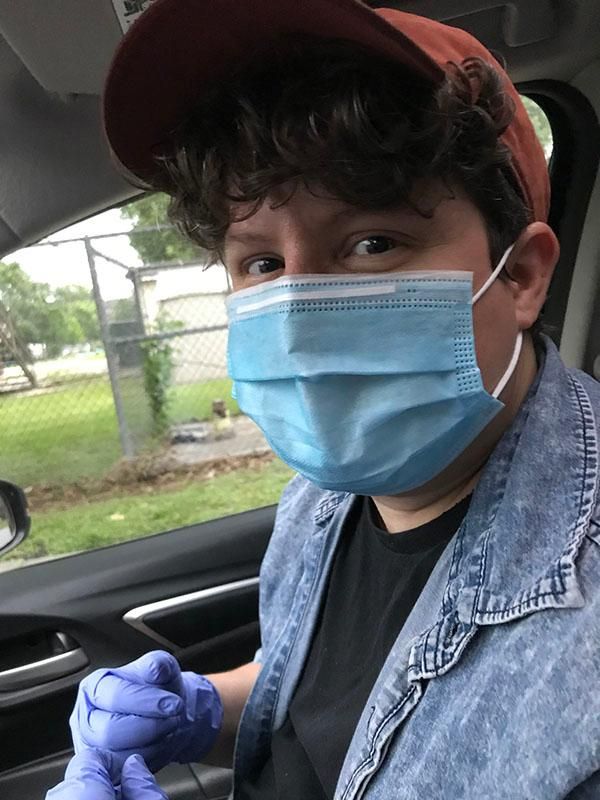

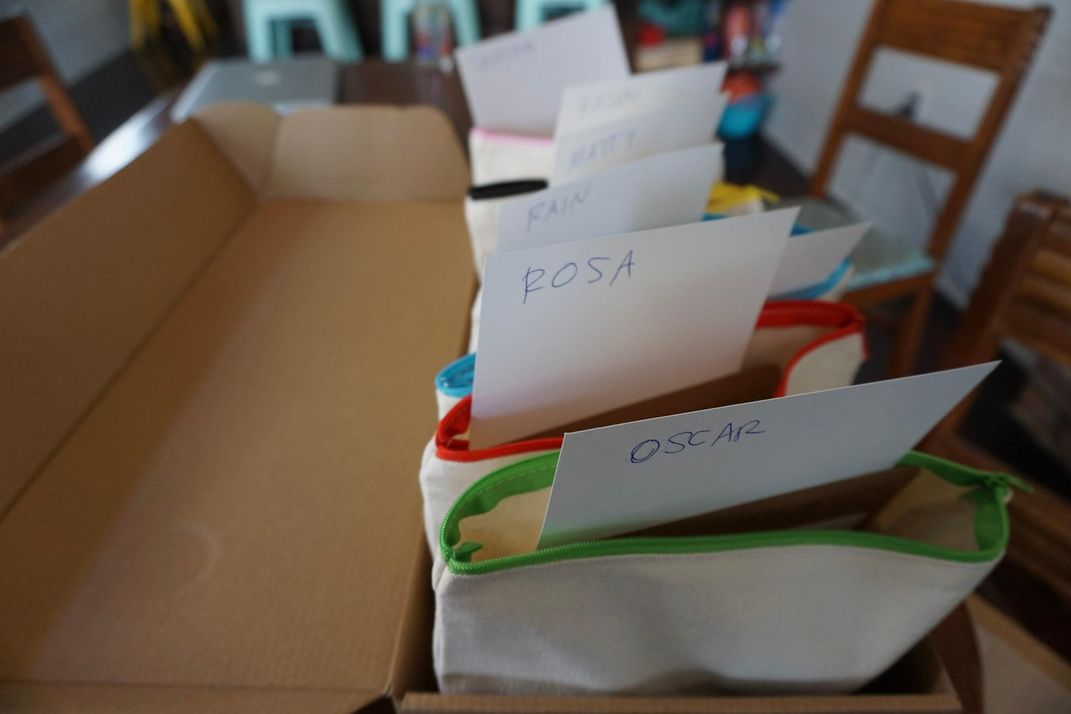

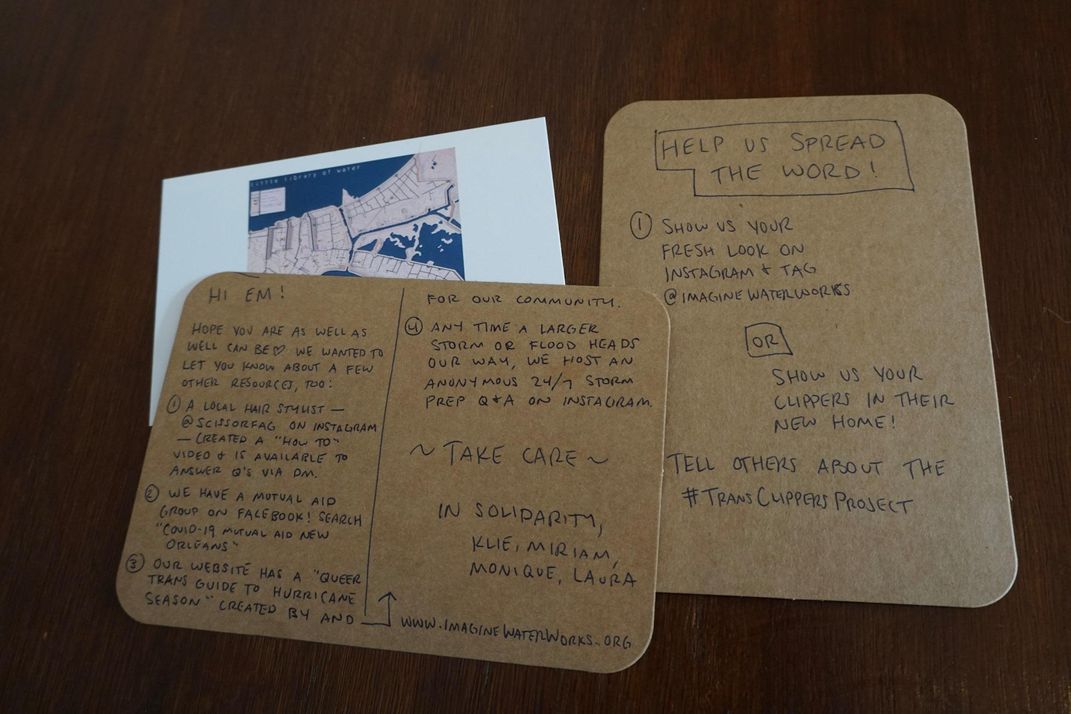

The Facebook post spurred Kliebert to help transgender and nonbinary community members access hair supplies safely during quarantine. After speaking to local queer hairstylists and barbers, Kliebert conceived of the Trans Clippers Project. Now, through an online form they created, those in need can order a pair of clippers for free. Once requested, Kliebert and other volunteers individually package the supplies, each with a personal note and a set of hair cutting guidelines, and then hand-deliver them to homes.

“You are an amazing human,” the original poster wrote to Kliebert, alongside a before and after picture of their new haircut. “Thank you so much for the clipper exchange.”

Since then, the Trans Clippers Project has flourished. After Kliebert posted another Facebook message that was shared almost 2,000 times with details on how to request clippers and the opportunity to start a local team, the project has spread to 18 states, from California to Massachusetts, and Texas to Minnesota. There is also a new team starting in Toronto. With the help of almost 160 individual and company donors, this program has sent more than 200 clippers to trans and nonbinary folks as of mid-June.

“We’re combining our knowledge of disaster preparedness with our knowledge of what it’s like to be queer,” says Kliebert. “It’s about caring for people who are unseen. That’s where our entire organization tries to step up.”

To get around the hair clipper shortage, Kliebert bulk ordered supplies during the early days of the pandemic, before cisgender people—those whose gender identity is the same as their birth sex—started thinking about quarantine haircuts. “We saw the need before anyone else saw it,” says Kliebert. Yet, as the primary organizer for all of the Trans Clippers operations nationwide, keeping up with demands has been a challenge. Finding quality clippers is difficult during the pandemic, says Kliebert, and many Wahl clippers are currently out of stock.

Luckily, Trans Clippers Project’s deliveries are still going out. Ezekiel Acosta, who lives in East Chicago, Indiana, a city on the border of Illinois, recently received a package of 16 brand new hair clippers to distribute to those in need. As a transgender man, Acosta understands how vital a haircut is. “When I came out, the first thing I did was cut my hair—that’s a big step forward for many queer folks,” he says. But, “going to a barber shop can be daunting,” he adds, and some trans folks experience harassment when in a salon. Therefore, providing an easy and safe way for them to cut their hair is crucial.

Along with the clippers, Acosta, who is a lead organizer for the Trans Clippers Project in Indiana and Illinois, received clear instructions on how to distribute them in a safe, socially distant manner. So far, he has delivered five care packages, each of which includes a mirror, hairbrush, face mask and information on mental health care. With word of the project quickly spreading, Acosta says he will deliver all 16 clippers in no time. “The biggest thing about this project is creating as few barriers [for the trans community] as possible,” he says. “There are not many times trans people are just given equipment and resources.” Acosta plans to continue this project post-COVID-19, with the possibility of expanding it to include free haircuts for trans people at local barber shops.

The Trans Clippers Project is one of many programs launched by Imagine Water Works. Founded in 2012, the organization helps communities prepare for and reduce the risks of pollution, flooding and other natural hazards. Early on, the group drafted legislation to push for green infrastructure in the New Orleans area and created a guidebook that teaches residents how to reduce water pollution and small-scale flooding in their neighborhoods.

Yet over the years, co-founder Miriam Belblidia noticed that the communities most vulnerable to climate disasters—including people of low socioeconomic status, people of color and trans individuals—are often left out of key conversations on infrastructure planning. “That shifted the kinds of materials that we were creating,” says Belblidia. Now, much of Imagine Water Works’ focus lies in developing tools that can help underserved populations survive and thrive. For example, they recently made a hurricane season guide for transgender, nonbinary and two-spirit (those who have both male and female spirit in the Indigenous community) people—all of whom face obstacles, like remembering to take their ID card with their correct gender out of their home during a flood, that are not addressed in a typical natural disaster guide.

By giving these groups a seat at the table, we will all benefit in the long run, says Kliebert. “We believe the people who are unseen are the people who know how to move forward in this world,” they say. Every member of Imagine Water Works is queer, and many of them are first-generation immigrants. “Folks like us…we know how to find a future when the world doesn’t necessarily want us to have one.”

Kliebert sees the success of the Trans Clippers Project as an example of how small teams on a shoestring budget can address critical needs within their community. As other issues like police brutality and racism continue to plague this country, Kliebert wonders whether this project can serve as a prototype for institutions moving forward. “Within weeks, we were able to mobilize organizers in 18 states and two countries,” says Kliebert. “Now the question is: How can that model be replicated for other disaster or justice movements?”