New Software Can Actually Edit Actors’ Facial Expressions

FaceDirector can seamlessly blend several takes to create nuanced blends of emotions, potentially cutting down on the number of takes necessary in filming

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/45/464582dd-3b2f-4131-bd3b-74cc35586d3a/42-27347531.jpg)

Shooting a scene in a movie can necessitate dozens of takes, sometimes more. In Gone Girl, director David Fincher was said to average 50 takes per scene. For The Social Network actors Rooney Mara and Jesse Eisenberg acted the opening scene 99 times (directed by Fincher again; apparently he’s notorious for this). Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining involved 127 takes of the infamous scene where Wendy backs up the stairs swinging a baseball bat at Jack, widely considered the most takes per scene of any film in history.

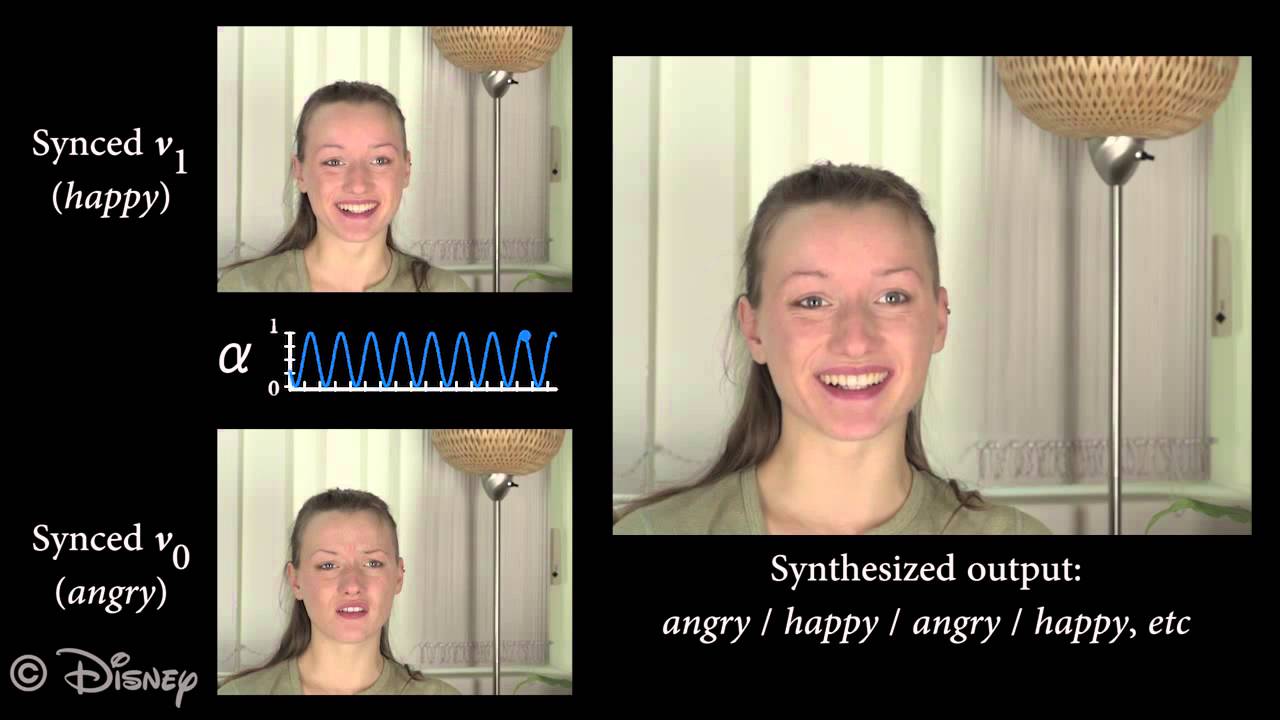

A new software, from Disney Research in conjunction with the University of Surrey, may help cut down on the number of takes necessary, thereby saving time and money. FaceDirector blends images from several takes, making it possible to edit precise emotions onto actors’ faces.

“Producing a film can be very expensive, so the goal of this project was to try to make the process more efficient,” says Derek Bradley, a computer scientist at Disney Research in Zurich who helped develop the software.

Disney Research is an international group of research labs focused on the kinds of innovation that might be useful to Disney, with locations in Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Boston and Zurich. Recent projects include a wall-climbing robot, an “augmented reality coloring book” where kids can color an image that becomes a moving 3D character on an app, and a vest for children that provides sensations like vibrations or the feeling of raindrops to correspond with storybook scenes. The team behind FaceDirector worked on the project for about a year, before presenting their research at the International Conference on Computer Vision in Santiago, Chile this past December.

Figuring out how to synchronize different takes was the project’s main goal and its biggest challenge. Actors might have their heads cocked at different angles from take to take, speak in different tones or pause at different times. To solve this, the team created a program that analyzes facial expressions and audio cues. Facial expressions are tracked by mapping facial landmarks, like the corners of the eyes and mouth. The program then determines which frames can be fit into each other, like puzzle pieces. Each puzzle piece has multiple mates, so a director or editor can then decide the best combination to create the desired facial expression.

To create material with which to experiment, the team brought in a group of students from Zurich University of the Arts. The students acted several takes of a made-up dialogue, each time doing different facial expressions—happy, angry, excited and so on. The team was then able to use the software to create any number of combinations of facial expressions that conveyed more nuanced emotions—sad and a bit angry, excited but fearful, and so on. They were able to blend several takes—say, a frightened and a neutral—to create rising and falling emotions.

The FaceDirector team isn’t sure how or when the software might become commercially available. The product still works best when used with scenes filmed while sitting in front of a static background. Moving actors and moving outdoor scenery (think swaying trees, passing cars) present more of a challenge for synchronization.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)