A New Study Brings Scientists One Step Closer To Mind Reading

Researchers have developed a technique that uses the brainwaves captured by EEG machines to reconstruct the images you see

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/11/e211b6fc-3746-42f5-b63a-76bf1804a330/dan_nemrodov_research-6-web.jpg)

A crime happens, and there is a witness. Instead of a sketch artist drawing a portrait of the suspect based on verbal descriptions, the police hook the witness up to EEG equipment. The witness is asked to picture the perpetrator, and from the EEG data, a face appears.

While this scenario exists only in the realm of science fiction, new research from the University of Toronto Scarborough brings it one step closer to reality. Scientists have used EEG data (“brainwaves”) to reconstruct images of faces shown to subjects. In other words, they’re using EEG to tap into what a subject is seeing.

Is it mind reading? Sort of.

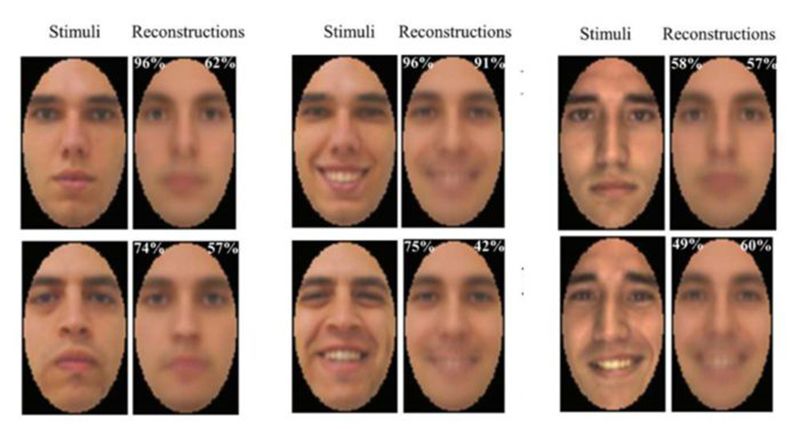

When we see something, our brains create a mental impression or “percept” of the thing. In the study, researchers hooked up 13 subjects to EEG equipment and showed them images of human faces. The subjects saw one happy face and one neutral face for 70 different individuals, for a total of 140 images. The faces each flashed across the screen for a fraction of a second. The recorded brain activity, both individual data and aggregate data from all subjects, was then used to recreate the face using machine learning. The reconstructed images were then compared to the original images. The aggregate data produced more accurate results, but individual data was also more accurate than random chance.

Prior to this, scientists had reconstructed images using data from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Some of this research was done at the University of Toronto Scarborough, in the very same lab. Other recent work involved implanting electrodes in the brains of macaques to learn how neurons responded when the monkeys looked at faces, which gives scientists a better understanding of how humans create face images.

“What makes the current study special is that the reconstruction in humans was obtained using a relatively cheap and common tool like EEG,” says Dan Nemrodov, postdoctoral fellow at UT Scarborough who developed the technique. The research was recently published in the journal eNeuro.

EEG is able to capture visual percepts as they’re developing, Nemrodov says, while fMRI captures time much more poorly. The researchers were able to use the EEG technique to estimate that it takes the brain 170 milliseconds (0.17 seconds) to make a representation of a face we see. The team hopes their method could be used alongside fMRI techniques to make even more accurate reconstructions.

Nemrodov stresses that the technique in the study used perceived stimuli. In other words, it was reconstructing what subjects were seeing, not what they were thinking.

But the team is now studying whether images could be reconstructed from memory or imagination.

“[This] would open numerous possibilities starting from forensic, such as reconstruction of appearances of people seen by witnesses based on their brain signal, to non-verbal types of communication for people with impaired abilities to communicate, to integration of these systems as parts of a brain-computer interface for professional and entertainment purposes,” Nemrodov says.

For people who can’t speak, the technique could potentially allow them to express themselves by showing images of what they perceive, remember or imagine. Suspect images could theoretically be more accurate. The research could also potentially yield understandings of how the brain sees faces that might help people with congenital prosopagnosia, commonly known as face blindness. People with this condition are unable to recognize faces, no matter how familiar.

Despite the science fiction vibe of the research, Nemrodov says we shouldn’t be worried about sinister, dystopian uses.

“There is little reason to suggest that we will be able to read peoples’ minds against their will using our method,” he says. “In order to produce accurate results we rely on participants’ collaboration in paying attention to presented stimuli.”

There are ethical issues when it comes to using brain scans to reproduce images, says Jack Gallant, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of California, Berkeley. But these issues won’t be relevant until interfaces for decoding brain waves are much more advanced. In order to make image reconstruction a useful tool for much of anything, we need a device that’s both portable and can measure at high resolution, capturing both spatial and temporal dimensions.

“We don’t know when such a device would become available,” Gallant says. “If we knew how to build that thing, we’d would be building it already.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)