This Orb-Shaped Solar Power Device Works On The Cloudiest Days

The use of a clear “ball lens” to concentrate light into a beam of energy may improve solar power efficiency by up to 50 percent

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06/a1/06a19554-b62b-44fc-b085-ddea2656c57f/orb_1.jpg)

Nearly six years ago, futurist Ray Kurzweil predicted that, within 20 years, solar power technology would advance to the point where it would be able to supply all of the world’s energy needs. His optimistic forecast wasn't too far-fetched considering that the amount of energy Earth receives in just one hour would be enough to power humans' lives for an entire year. But now, even the most ardent supporters are no longer willing to help subsidize this once bright vision of the future.

As it turns out, effectively harnessing the sun’s immense potential is an incredibly fickle endeavor. Only certain countries are geographically fortunate enough to receive ample sunlight year-round, while inclement weather further disperses and thus dilutes the amount of usable energy that reaches solar harvesting systems below. More importantly, the maximum theoretical conversion efficiency of conventional silicon-based photovoltaic cells is about 33.7 percent, meaning that 33.7 percent of all sunlight hitting a cell can be converted into electricity. Put simply, the most optimal way of producing solar power is still too cost prohibitive to compete.

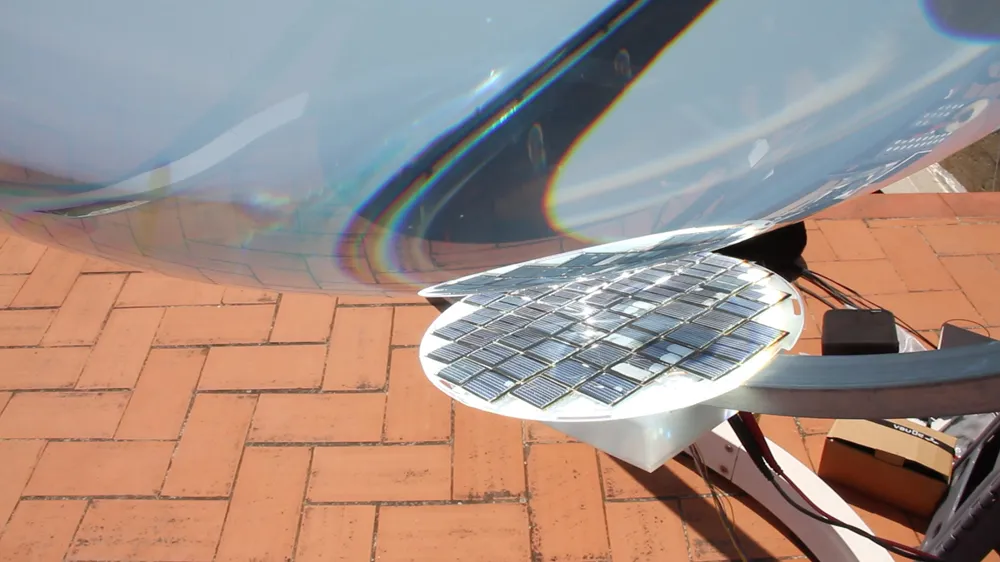

German architect André Broessel, who's thought long and hard about these insufficiencies, claims that he’s invented a model device that’s designed to get around these bottlenecks. Fundamentally, his Betaray concept isn't a radical departure from other panel technologies out there since it also uses solar cells to collect sunlight. The energy, however, arrives in the form of an energy-dense beam that's concentrated up to 10,000 times. Above the miniature array of solar cells is a large water-filled glass orb that works similarly to a magnifying glass in focusing the light that’s present during all sorts of less-than-ideal conditions, like when skies are cloudy or when the only available light is the low-intensity illumination reflected by the moon.

Broessel estimates that the clear "ball lens" helps improve efficiency by up to 50 percent annually—all while using a cell arrangement that comprises less than 25 percent of the silicon cell area found in most systems. "Most of the expensive aspects of solar systems come from the production of cells, which also leads to a high carbon footprint," Broessel says. "And when there's lousy weather, the production is equivalent to peanuts, even when they're in perfect position.”

The Betaray utilizes what Broessel calls a dual-axis tracking feature to monitor the continually changing position of the sun and adjust accordingly to maximize input. Unlike systems with computerized solar trackers, often employed on large solar farms, the prototypes he has assembled can be used indoors. They can be retrofitted along the wall of a building in place of windows, considering that they are 99 percent transparent.

The device is compatible with the entire range of existing solar cell systems, though it may be particularly suitable for high-efficiency multijunction solar cells that also happen to necessitate the use of concentrator lenses to work. These more advanced systems boast a 43 percent conversion efficiency with a maximum theoretical efficiency of upwards of 70 percent. Broessel says internal tests have already demonstrated that the latest Betaray model produces about 150 watts per square meter when it is perpendicular to the sun. This rate is on par with some of the most efficient PV systems out on the market.

Juris Kalejs, chief technology officer at solar systems developer American Capital Energy, acknowledges that Broessel's concept does confer some advantages—especially for consumer looking for simpler, more versatile alternatives—but expressed some skepticism. "It's a very tricky system to make," he told Discovery News, "and you need to make it on a large scale to make it cost effective."

Broessel, however, disagrees and counters that Betaray can be cost effective when taking into account the totality of not only production costs, but also projected savings on the owner's energy bills in the long term. He points out, for instance, that constructing the device involves “very basic materials,” like water and glass, that cost less than manufacturing photovoltaic cells.

"You can optimize the conversion of light into energy all year round, even in bad weather," he says. “It's not unrealistic to think that in a year, it can double your energy yield.”

For now, Broessel's hoping to raise money through the sales of an unnamed "gadget" still under development. Within three years, he expects to have amassed enough funding to go into production with the Spherical Solar Energy Generator. But, it is a tough goal, he has found.

"All of Europe knows about my project," Broessel declares. "I have a month to pay for the patent rights, otherwise it will become open source. And by then, everyone will know about it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tuan-nguyen.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tuan-nguyen.jpg)