Patent Pending

The Supreme Court may soon reinvent the rules for invention

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/patent_barb_388.jpg)

This past November the Supreme Court heard arguments in what could become the first landmark patent case in 40 years. The particulars of the case—whether one company has the right to patent an adjustable car pedal—leave room for excitement. But the impending ruling, which is expected sometime soon, has incited debate between the health-care and technology industries, one of which could benefit greatly from the outcome.

At issue: whether to change the standard for considering an invention "obvious"—and therefore ineligible for patent.

"There's been a shadow over the obviousness standard for quite a while," says patent attorney Michael R. Samardzija, who is the director of intellectual property at the University of Texas-M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

The concept of patents dates back to 15th-century Venice, says Steve van Dulken, a historian and author of American Inventions. Most patent systems simply allowed inventors to register an idea. But the U.S. Constitution granted scientists and artists "the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries," and courts began eliminating "obvious" or repetitive inventions.

The Supreme Court last ruled on patent guidelines in the 1966 case Graham v. John Deere Co. Since that time, the Federal Circuit, which is the appellate body for patent cases, has instituted guidelines known as the "suggestion test" that make patenting an invention difficult.

To be deemed patent-worthy, an invention must meet two criteria. It must be novel, and it must be "non-obvious." The first is clear enough. Say, for example, you invent a four-legged swivel chair. The chair is novel if no other patent mentions each of its defining aspects: having four legs and a swivel function. Still, it's possible that two separate patents—a standard chair and a lazy Susan, perhaps—"suggested" at your creation. Such suggestions don't fly under the suggestion test; for your chair to be non-obvious, the creation must have sprung independently from these two previous, separate ideas.

The suggestion test's high threshold makes patent-worthiness difficult to achieve. The health-care sector, represented in the current case by Teleflex, would like to keep it that way, explains Samardzija. Pharmaceuticals take dozens of years and billions of dollars to patent, and a low patent threshold would make it possible for other companies to claim similar products.

On the other hand, the technology industry, represented in the current case by KSR International, would like the standard lowered. Tech companies rely less on patents and more on brand name; if Microsoft and IBM create a similar product, they'll simply cross-license the idea and avoid litigation, Samardzija says. With a looser "obvious" rule, tech companies could invalidate patents held by pesky small companies—such as the Virginia firm that received a $612.5 million settlement from BlackBerry in early 2006.

"The argument is that [the suggestion test] was never explicitly or implicitly formulated by the Supreme Court," Samardzija says. "Having a Supreme Court imprimatur on it would be very beneficial to patent law as a whole."

Some patents that seem "obvious" now but weren't in their day:

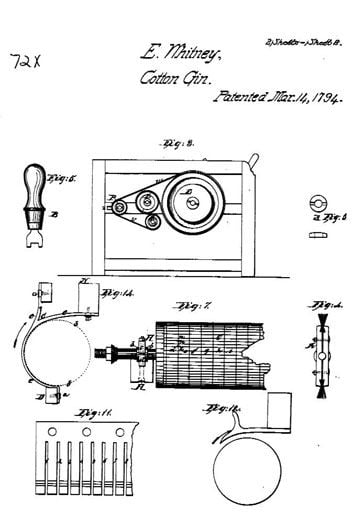

Cotton Gin

Inventor: Eli Whitney

Date: March 14, 1794

Of Note: Only the 72nd patent overall (the first was a method for making pot ash). Whitney's gin was approved by James Madison, a key implementer of the Constitution's patent clause (Article I, paragraph 8, section 8)

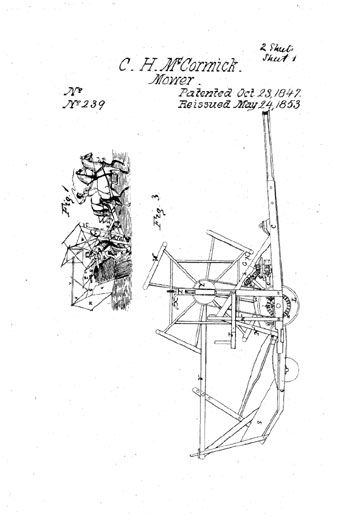

McCormick's Reaper

Inventor: Cyrus McCormick

Date: June 21, 1834

Of Note: "It was perfect for farming the Midwest, but not for the rocky soils of New England," van Dulken says. "It helped encourage migration west."

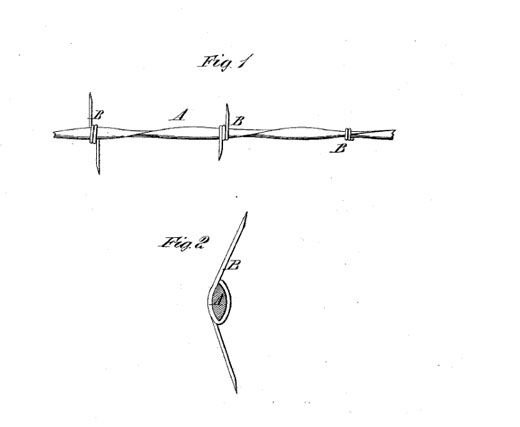

Barbed Wire

Inventor: Joseph F. Glidden

Date: November 24, 1874

Of Note: Designed for "preventing cattle from breaking through wire-fences," Glidden writes in his application.

Cigarette rolling machine

Inventor: James A. Bonsack

Date: March 8, 1881

Of Note: As with the sewing machine, shoe lasting and linotype, Bonsack's invention was a facilitator of "things had been previously done by hand," van Dulken says.

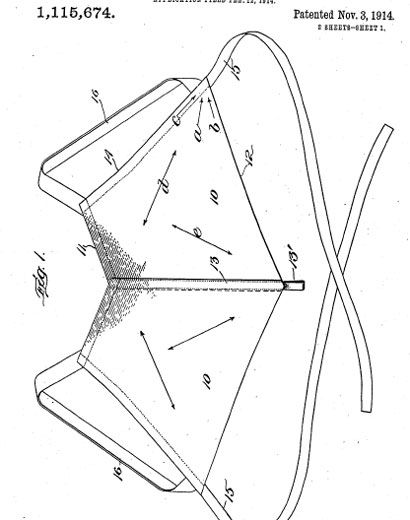

Brassiere

Inventor: Mary P. Jacob

Date: November 3, 1914

Of Note: Claims to solve the problem of garments that required tying laces in the back, which interfered with "the wearing of evening gowns cut low."

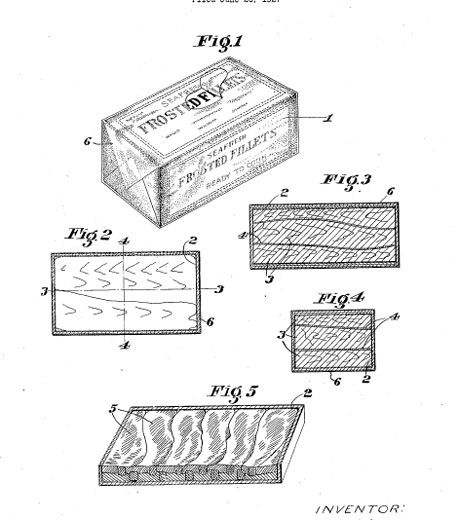

Frozen Foods

Inventor: Clarence Birdseye

Date: August 12, 1930

Of Note: The food would have "substantially" the same structure as it had before it was frozen, and would retain "its pristine qualities and flavors," Birdseye writes.

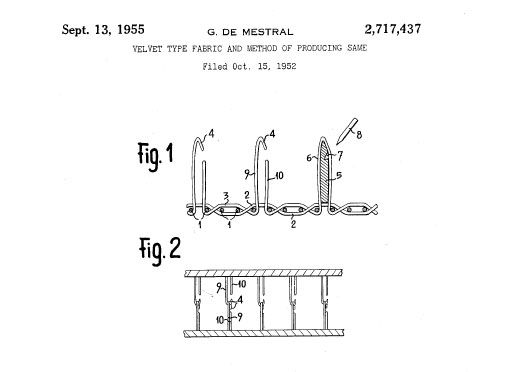

Velcro

Inventor: George de Mestral

Date: September 13, 1955

Of Note: This invention is a result of a new technology enabling novel devices, van Dulken says. Where de Mestral's invention failed with cloth texture, it succeeded with nylon, patented in 1937 by Wallace Carothers.

Post-It Note

Inventor: Spencer Silver

Date: September 12, 1972

Of Note: In the late 1960s, Silver wandered around his lab soliciting applications for a poor-quality glue. His colleague Art Fry suggested using it for a removable bookmark.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)