Scenes From a Changing Planet

Landsat satellites have been taking photos of Earth for a long time, but only now can you watch zoomable, time-lapse images of the planet’s transformation.

![]()

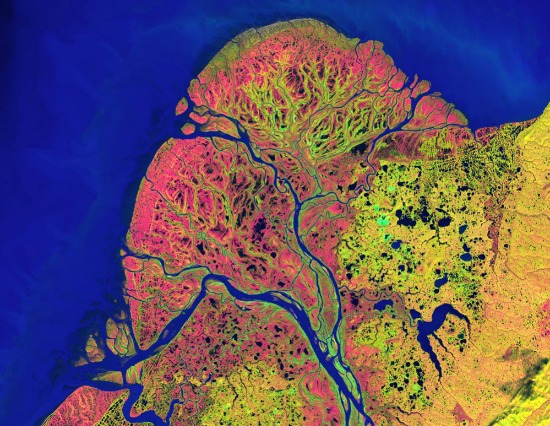

Landsat image of Alaska’s Yukon Delta. Photo courtesy of NASA

For 40 years Landsat satellites have been circling the Earth, taking pictures from roughly 440 miles above us. Each loop lasts about 99 minutes and it takes about 16 days to capture the entire planet. Which means that Landsats have been recording, in 16-day intervals, the ebb and flow of our relationship with the planet since the early 1970s.

It’s been, as they say in the relationship business, a rough stretch, but for most of it, only scientists have been paying much attention. These were people tracking the explosion of cities or the scarring of rainforests or the melting of glaciers. As for the rest of us, well, we may have been aware that things were changing, and not for the better, but we had little sense of the scale or pace of change.

Now we can see for ourselves, thanks to a joint project of Google, the U.S. Geological Survey and Carnegie-Mellon University. Google has already stored 1.5 Landsat million images in its Google Earth Engine and now CMU scientists have refined software that allows many of those images to be watched as zoomable, time-lapse videos.

It’s an experience both fascinating and sobering. Take, for instance, a satellite timelapse of Las Vegas since 1999. You see the city speading like kudzu into the desert, while nearby, Lake Mead shrinks a bit more every year. The two aren’t directly related–the lake’s being drained by drought and warm winters upstream on the Colorado River. But if you live anywhere near there, it couldn’t be a comforting juxtaposition.

Or consider a time lapse of the Amazon rainforest during the same period. You watch as farmers’ fields spider out like veins from a road built through the green canopy. And when brown fields take over an area, another road is cut and more fields follow. As Carnegie Mellon scientist Randy Sargent put it, “You can continue to argue about why deforestation has happened, but you no longer will be able to argue whether it happened.”

Archaeology from space

It turns out that satellite photography isn’t just a powerful tool for tracking recent Earth events; it’s also a way to look deep into the past. A report published earlier this year revealed that archaeologists are able to see traces of now-buried ancient settlements by applying a computer program to satellite photos. This works because human settlements, specifically organic waste and decayed mud bricks, leave behind a unique signature in the soil. Under infrared analysis, it tends to be much denser than the soil around it.

Using this technique, Harvard archaeologist Jason Ur was able to spot as many as 9,000 potential hidden settlements in a 23,000-kilometer area of northeastern Syria alone. “Traditional archaeology goes straight to the biggest features — the palaces or cities — but we tend to ignore the settlements at the other end of the social spectrum,” said Ur. “The people who migrated to cities came from somewhere; we have to put these people back on the map.”

Another scientist using satellite images, Sarah Parcak, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, actually refers to herself as a “space archaeologist.” Last year she located as many as 17 possible small pyramids buried under the sand in Egypt through a satellite survey. Said Parcak, “It’s an important tool to focus where we’re excavating. It gives us a much bigger perspective on archaeological sites. We have to think bigger and that’s what the satellites allow us to do.”

The View

Here’s a sampling of some of the more memorable images captured by satellite cameras:

- An Olympian effort: In the spirit of the Games, NASA has pulled together aerial views of the 22 cities that have hosted the Summer Olympics since the modern games began in 1896.

- Growth spurts: While we’re peering down at cities, here are 11 more that have seen explosive growth in recent decades, from Chandler, Arizona, which has eight times as many residents as it did in 1980, to the Pearl River Delta in China, which was completely rural in the 1970s and now has a population of more than 36 million.

- Scorched Earth: Only a satellite image can give you a true sense of how much devastation the Waldo Canyon fire did in Colorado earlier this summer.

- Beetle mania: More ugliness in Colorado: A satellite’s view of the destruction done by the tiny pine bark beetle.

- Breaking away: A series of satellite images captures an ice island twice the size of Manhattan breaking away from the Petermann Glacier in Greenland a few weeks ago.

- Dust never sleeps: This will make you throat go dry: A dust storm bridging the Red Sea.

- Is this place beautiful or what?: And finally…to mark Landsat’s 40th birthday, NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey asked people to vote for the Landsat image that best presented Earth as a work of art. Here are the five top choices. .

Video bonus: Check out more stunning Landsat images in this clip about how the Google Earth Engine will make it much easier for people like you and me to to follow the Earth’s transformation.

More from Smithsonian.com

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)