Scientists Are Recording 24-Hour Soundtracks of Rainforests

The bioacoustic data gives Nature Conservancy researchers clues about the health of an ecosystem

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ed/bc/edbcb76f-1f3d-47a3-96b6-62368c9631dd/img_9109_edited.jpg)

In the dense rainforest of Papua New Guinea's Adelbert Mountains, birds-of-paradise, flightless cassowaries, frogs and insects are constantly making noise. But as the forest gets more developed, that could be changing. A group from the Nature Conservancy is keeping tabs on the health of the ecosystem by listening to its soundtrack.

The researchers have been working with community groups in the region for 15 years, trying to help them establish land use plans that sustain the growing communities and the forest’s native flora and fauna in the face of logging, clearcutting and farming. They had been doing small-scale sound recording, but now, with new technology, the group is recording day-long tracks and using a new technique to analyze the sound they record.

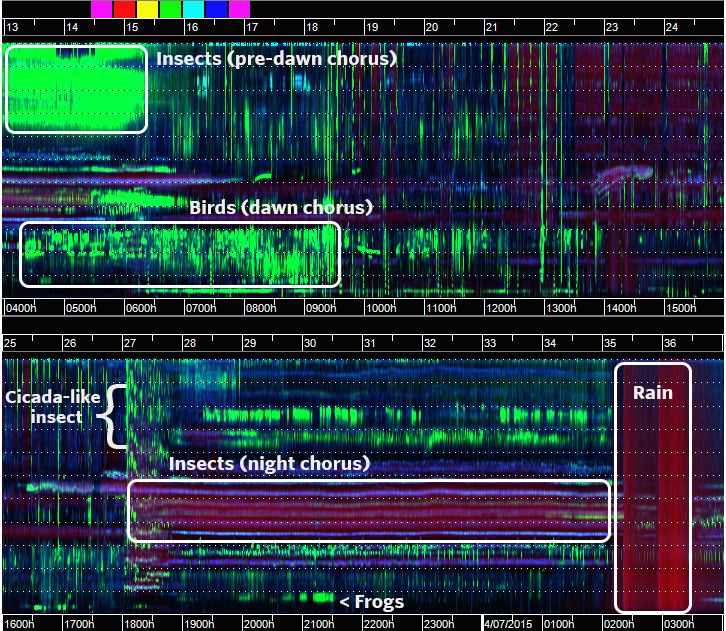

The Nature Conservancy scientists strapped a handful of digital recorders—some acoustic, meaning they can pick up sounds humans can hear, and others ultrasonic, catching noises beyond the human range, but all with SD cards that could hold a whole day of recording—to trees in 35 evenly spaced test plots. In each plot, they recorded for a full 24 hours, to get a baseline for how the forest's sounds change in that period of time.

“We thought it was important to see what happened over a day, otherwise it would be hard to know what would be a good sampling schedule,” says Eddie Game, the Nature Conservancy's lead scientist for the Asia Pacific region and this project.

He and his team worked with computer scientists at the University of Queensland, who built an algorithm to analyze the data and pick out patterns, such as the frequency birds vocalized at and the times of day certain insects chirped.

“It’s non-invasive, fast, cost-efficient and high fidelity. It’s a bit of a holy grail,” says Game.

Bioacoustics give the researchers a broad picture of what’s going on in the ecosystem without them having to painstakingly count individual animals, the way they would in a traditional fauna survey.

“Sound is terrific because it captures a lot of stuff that is localized,” Game says. “We can look at indexes of sound as a gross measure of what’s happening in the landscape. Frogs, bats, insects, birds, they’re all vocalizing, and in an ideal intact forest, they all vocalize at different frequencies and patterns. As you lose species, you lose pieces of that spectrum.”

Game and his team are using those sound spectra to show how development impacts animals across a landscape. Commercial logging operations are constantly looking to go into the mountains in the area, and there’s also pressure from tribal groups who cut into the forests for farms and community gardens and depend on subsistence agriculture. According to Game, the community groups he and team work with don’t necessarily see eye-to-eye about how to use the land, so they’re trying to come up with data to support the idea of working together and leaving broad swaths of the forest untouched. He is curious to see if the size of the protected piece of land matters.

They built out a minute-by-minute model of what a healthy intact forest sounds like, and then used that as a baseline to compare to landscapes that had more logging or agriculture. In each test area, they deploy the recorders and then collect them 24 hours later.

“What’s really evident is how different sound is in the forests compared to the zones where they’re doing agriculture or home gardens,” Game says. “What’s obvious is the temperature effect. In the cleared areas, it gets way hotter and you can see how that impacts species.”

Other scientists are doing sound recording studies, but they’re mainly doing shorter recordings at single sites.

“We’re the only ones looking at sound at a landscape scale,” Game says. “Soundscaping ecology is right at the beginning of a big revolution.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0196_2.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0196_2.JPG)