Show Stopper

The classically trained dance star Alicia Graf showed true grit overcoming a career-threatening ailment

Alicia J. Graf was waiting at the Alvin Ailey dance studio in Manhattan for the bus to the airport. She was dressed in jeans and a soft gray sweater, her voluminous curls, usually worn loose, pulled back in a knot. She was clutching dozens of pages of a grueling tour schedule that would dictate the next 16 weeks of her life. First stop: Jackson, Mississippi, then several other cities in the South, a hop up to Chicago, finally winding down with shows in Boston and elsewhere in the Northeast. "I've never danced so much in my life, day after day after day," Graf, 28, says with a smile. "I guess I'm the type of person who feeds off of challenges."

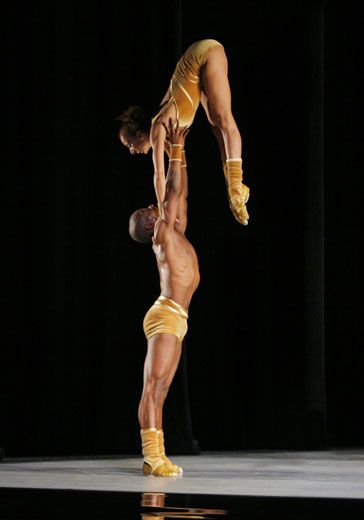

This is only Graf's second season with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, one of the United States' most successful dance companies, but Graf has already emerged as a star—though "star," strictly speaking, is not in the Ailey vocabulary. Ailey dancers are listed in alphabetical order, there are no rankings—no soloists, no corps de ballet—and everyone dances large roles and small. Still, critics have singled out Graf for praise. When she danced in "Reminiscin' " in 2005, the New York Times said her performance "stopped the show." Last December, an image of her gazelle-like form landed on the cover of Dance magazine, though the article also featured two other longtime Ailey "goddesses," Hope Boykin and Dwana Smallwood. "To be included in that group of women after a year of being here was such an honor," Graf says without a trace of diva attitude. "Alicia is an absolutely lovely person," says Ailey's artistic director, the legendary Judith Jamison. "And very humble, very unassuming."

Graf embodies the passion and dedication it takes to be a top-flight dancer—"She rehearses like crazy," says Jamison—yet she also knows there's life beyond dance. A professional ballerina by age 17, she suffered a mysterious leg ailment at 21 that kept her off her toes for four years: she didn't know if she'd ever perform again. "I just appreciate every day I am able to dance," she says. "But at the same time, the world is so much bigger to me because I've had other experiences." She thinks that someday, when she's no longer dancing, she might become a lawyer who works with artists and performers.

Growing up in Columbia, Maryland, Graf papered her bedroom walls with pictures of her idols: ballerinas Cynthia Gregory and Virginia Johnson, as well as Jamison herself when she was a young Ailey dancer. Graf wanted to be a ballerina for as long as she could remember, and started classes at age 3 or 4. Her life was school ("I was a nerd") and ballet class, including two summers at the School of American Ballet in New York. At 15, she traveled to St. Petersburg, Russia, for a competition at the splendid Mariinsky Theatre, home of the Kirov Ballet, and won in the contemporary dance division. "There was such a community effort to get me there," says Graf. Aunts, uncles and ordinary people in her hometown chipped in to help pay her way—a single tutu cost $1,000, and the competition required six costume changes. "A lot of people in town began to follow Alicia from an early age," recalls her father, Arnold Graf, a community organizer. "It was a wonderful experience."

At 13, Graf caught the attention of the founder of Dance Theater of Harlem, Arthur Mitchell, when she performed in a youth program at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. She joined his company at age 17 and completed high school in New York City at the Professional Children's School. Three years later, she recalls, "I was coming into my own as a professional dancer, and I started to have all these pains, all of a sudden, and my knee blew up and my ankle blew up and I didn't know what to do." She had one operation and then another, but nothing helped. "It was just like a year and a half of hell." One day, riding the subway after a frustrating doctor's appointment, Graf looked up to see a Dance Theater of Harlem poster with her image on it. "I remember sobbing uncontrollably, rocking like a crazy person. People were looking at me like, what's wrong? That was the lowest point." "To have this meteoric rise and have it all end," says her father. "She's strong, but that was pretty tough."

Thinking she might never dance again, Graf enrolled in Columbia University as a history major (she graduated in three years). Her symptoms were finally diagnosed as reactive arthritis—a condition overlooked at first because she was so young. With the right medication, the pain and swelling diminished, and she began physical therapy. She also became deeply involved in "praise dancing," a form of worship by dancing to gospel music. "Everything I do, I do for God," Graf says. "No matter what the part is, if it's not spiritually driven, it's not dancing for me. It's just where I get my inspiration from." She'd interned at JPMorgan and was headed for a job on Wall Street when she ran into Mitchell at Lincoln Center one evening and asked if she could return to the company. "I had been taking ballet class again and I had to make a decision: Do I want to sit at a desk for the rest of my life, or try this?" Mitchell seemed surprised, but his answer was yes. A year later, Dance Theater of Harlem, facing financial problems, was forced to go on hiatus. Graf then auditioned for Ailey and joined the company in 2005.

For some ballerinas, the transition to modern dance would be unthinkable, but Graf threw herself into learning the technique that's the foundation for Ailey dancers. "At first," she says, "it was very awkward, but now I feel it's natural for my body. The hardest thing for me was dancing barefoot." Her favorite Ailey role is "Fix Me" in Revelations—a part that stuck with her the first time she saw the company, at age 12, in Baltimore.

When not on tour, Graf shares a house in Brooklyn with her two brothers and a sister. She says she likes to cook, and eats whatever she wants ("a cookie a day," usually chocolate chip). Among the books she's read lately are Sidney Poitier's autobiography and the inspirational best seller The Purpose-Driven Life.

"I've met a lot of dancers who are so depressed," Graf says. "They're chain smokers and they don't eat, they just dance. They're fighting to get roles and fighting for this and that and not giving their bodies anything. It kind of defeats the purpose—the joy in being a dancer."

Cathleen McGuigan is a senior editor and the national arts correspondent at Newsweek.