The Story of the Weber Grill Begins With a Buoy

When metalworker George Stephen, Sr. put two halves of a buoy together, he didn’t know he was making a charcoal grill that would stand the test of time

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/bc/33bc52a6-3757-46e0-ae2a-3d35bf001b2d/2587861804_2ffa1f6a19_o.jpg)

Labor Day often means sun’s out, buns out. Hamburger buns, that is. These days, many of the grills rolled out onto patios across America look more like spaceships than cooking devices. They cater to the technophile, sporting built-in thermometers and light-up knobs. But despite all the high-tech grilling gear, at least one classic has survived: the Weber kettle grill.

The Weber name is inextricably tied to backyard barbecues, but that wasn’t always the case. The domed charcoal grill, which many foodies swear gives the best flavor, traces its roots back to Weber Brothers Metal Works. Founded in 1887, the Chicago company produced a range of metal products, from hinges to wagons.

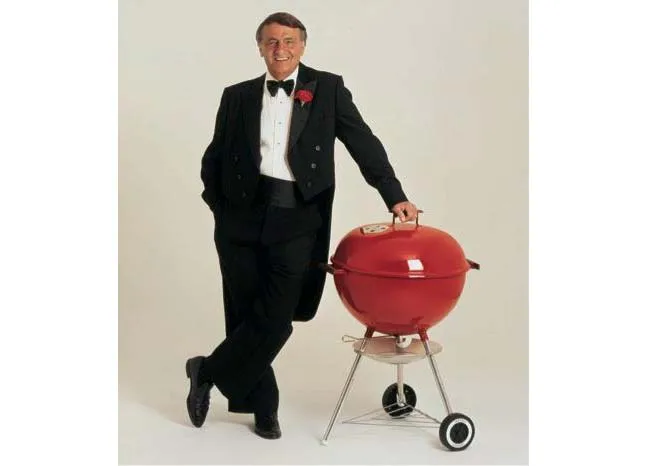

In the 1950s, George Stephen, Sr. worked in sales at Weber Brothers Metal Works, which his father ran at the time. He had an inventive mind “always tinkering with metal and springs and gadgets,” says Mike Kempster, chief marketing officer at Weber-Stephen Products, the current name for the company, which changed in 1958 when Stephen took over. He often worked on fabricating and selling innovative products, including mailboxes and fireplace equipment. But nothing really stuck, says Kempster.

Stephen and his growing family, which eventually included 12 children, frequently gathered to enjoy food cooked on the grill. “My father knew that one of the best ways to bring families together was through a shared meal enjoyed in the great outdoors,” his son Jim Stephen, now chairman of Weber-Stephen Products, once said.

At the time, the popular design was an open charcoal brazier. The appliance was composed of a metal box or tray to hold the coals with a grid iron resting above. But the open-top design of these devices left the meat vulnerable to weather. Big winds could kick up ash or set the precious meat ablaze, and rain would fill the grills with water. Even worse, backyard chefs had to breathe in the excessive smoke from the grill top and the meat rarely had an even cook.

So in 1952, fed up with ruined meals, Stephen set out to make a better grill.

At the time, Weber Brothers Metal Works was filling orders for metal buoys for both the Coast Guard and the Chicago Yacht Club. So Stephen took two of the half spheres for the buoys and created a grill.

“As the story goes,” Kempster says, “he took it home, he fired it up with charcoal, and it didn’t work. The fire went out.” One of his neighbors was watching the spectacle and chimed in saying, “George, you gotta let some air in that thing,” according to Kempster. So the pair grabbed a pick from his tools and punched some holes in the lid. It worked.

“That was research and development in 1952,” Kempster laughs.

The new grill design resolved all the pain points for consumers back in the 1950s, Kempster explains. The enclosed dome shape sealed in the smoky barbecue flavors and gave backyard chefs better heat control while cooking their meals. The lid also allowed backyard cooks to easily snuff out the coals when they were done cooking and prevented the barbecues from filling up with water.

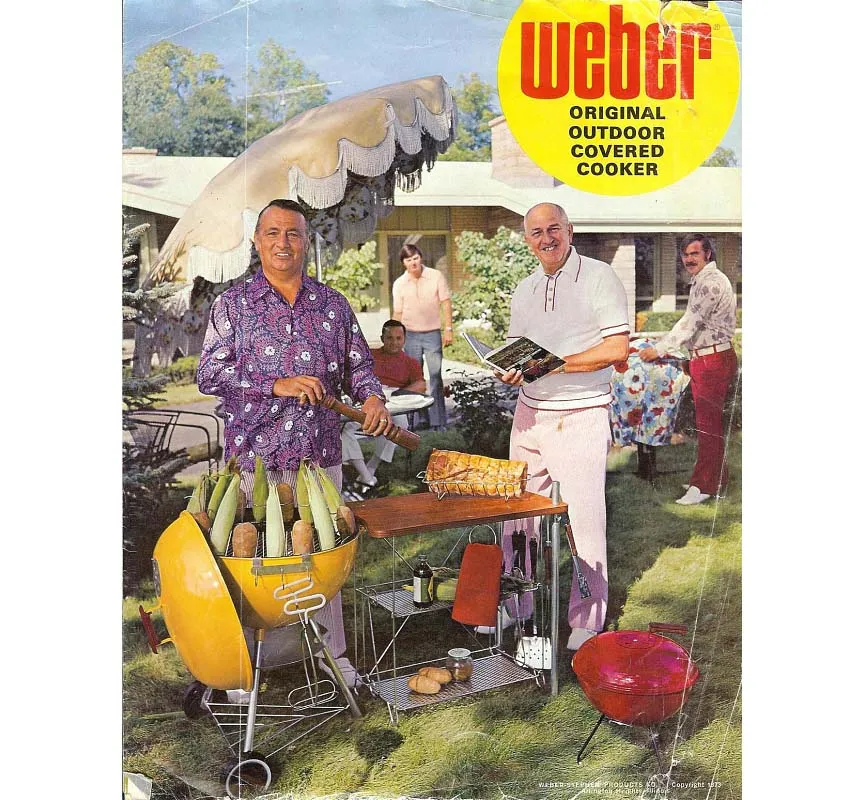

For a while, Weber-Stephens Products claimed the original kettle grill’s round body was superior to other grills on the market. “The unique dome shape reflects the heat evenly all around, just like a kitchen oven,” according to a Weber ad from the 1970s. But over years of testing, this assertion hasn’t held. “It reflects heat well, but we haven’t been able to prove it reflects heat any better than a square or a rectangle,” says Kempster, noting that the interior of kitchen ovens are rectangular. Grill efficiency lies in other design details, he explains, such as the positioning of the grates and air dampers.

Even so, “there’s a bit of a mystique in the shape,” says Kempster. “It’s a hard shape to manufacture because it takes really, really big presses to draw steel.” The design was also totally different than the boxy grills of the day. A popular early nickname for the ovoid grill was Sputnik.

Stephen marketed this first grill as “George’s Barbecue Kettle.” It sold for $29.95—the equivalent of around $270 today. He used the grill frequently to cook for family and friends and sold a few of them, but it took several years and many grill iterations later for the business to take off.

In the mid-1950s, his father told him that he had to make a choice, says Kempster, either he sells grills or he works at the metal company; he couldn’t do both. So without much financial backing, Stephen took a chance, struck out on his own and began to grow his burgeoning business.

After several successful years, Stephen returned to the company in 1958. “He scraped up enough money to buy out [his father’s] partner,” says Kempster and changed the company name to Weber-Stephen—keeping the “Weber” name in case the barbecue venture went up in flames. This safeguard gave him the option of returning to metalworking. But it wasn’t necessary; business was smoking.

From its modest roots Weber grew to be an internationally recognized name in the grilling world. The company grew from a small band of devotees to a massive business, pushing the edge of food technology at a time when backyard cooking was a rapidly growing fad.

Backyard barbecue first came about in the 1920s with the beginning of American suburbanization, explains Robert Moss, a culinary historian and author of Barbecue: The History of an American Institution. In the early days of grilling, many magazines started running feature articles on how to barbecue, highlighting it as a fun way to entertain, he says.

“Those early articles actually had instructions for digging a pit in the ground—a small pit,” says Moss. Those pits echoed the 19th century communal pit barbecues that eventually morphed into modern backyard grilling.

In the wake of World War II, the suburban rush took off and people began moving en masse away from the cities. An aura hung around backyard leisure. “America had shifted from being a rural country where you lived on a farm,” says Moss, “to being in the city and sort of feeling cut off.” Backyard leisure became “a release valve” from modern life, he says. This same desire for escapism led the growing Tiki culture—an adaptation of what was perceived as the tropical lifestyle.

This was also a period when America went meat crazy, explains Paula Johnson, curator for the exhibition, “FOOD: Transforming the American Table, 1950-2000,” on display at Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Meat was rationed during the war and, before that, in the Great Depression, meat and other food options were limited. “By the 1950s people were ready to enjoy a different kind of food,” says Johnson.

The squashed egg-shaped contraptions entered the market at a time when American middle class lifestyles were changing, grill technology lagged behind and people were hungry for meat.

Stephen was ready to serve it all up—grilled, roasted and broiled.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)