The Museum of Failure Showcases the Beauty of the Epic Fail

A new exhibition of inventions that bombed boldly celebrates the world’s most creative screw-ups

What’s not to love about My Friend Cayla, a doll designed to be a child’s best friend? Using speech recognition software and Google Translate technology, the talking companion can understand and respond to her young owners in real-time about her pets, hobbies and favorite foods. And by accessing the internet, Cayla—who in 2015 won the British Toy and Hobby Association’s coveted Innovative Toy of the Year award—can even answer questions about the world at large. The cardboard housing of the “first interactive doll” boasts: “I know so much about you!”

Maybe too much. Advocacy groups claim that Cayla’s sweet look of innocence masks a sinister side. By talking up Disney movies and characters, they say, she acts as a stealth shill for the studio, which pays for the advertising. And Cayla’s unsecured Bluetooth connection could allow a hacker to tap her private conversations and steal the personal data (home addresses, names of relatives) she prompts kids to provide. Earlier this year German parents were advised to disable or destroy Cayla over concerns that she can spy on the moppets who befriend her. The toy is now banned in Germany, where authorities have deemed it an espionage device.

The story of My Friend Cayla serves as an up-to-date object lesson in the new Museum of Failure, which is dedicated to innovation and design misfires. A lighthearted take on the creative process, the wide-ranging collection debuted this past June in Sweden and has its first U.S. pop-up this month at an exhibition sponsored by the SEE Global Entertainment company in Los Angeles. To be displayed an item must have been a product that led to an unexpected outcome and, on some level, bombed. “Cayla was a commercial success,” concedes Samuel West, the museum’s founder and curator. (The doll, manufactured by U.S.-based Genesis Toys, is still on the market, here and abroad.) “But the backlash made her a promotional disaster.”

West has rescued scores of monumental duds from the garage sale of history. “Each failure is uniquely spectacular,” he says, “while success is nauseatingly repetitive.” Among the objets trouvés—many of which were found on eBay—is the Sony Betamax video recorder, a LaserDisc, bottles of Heinz green ketchup and colorless Crystal Pepsi, coffee-flavored Coca-Cola BlaK, and Orbitz, a “texturally enhanced” beverage whose floating edible balls suggest nothing so much as a lava lamp.

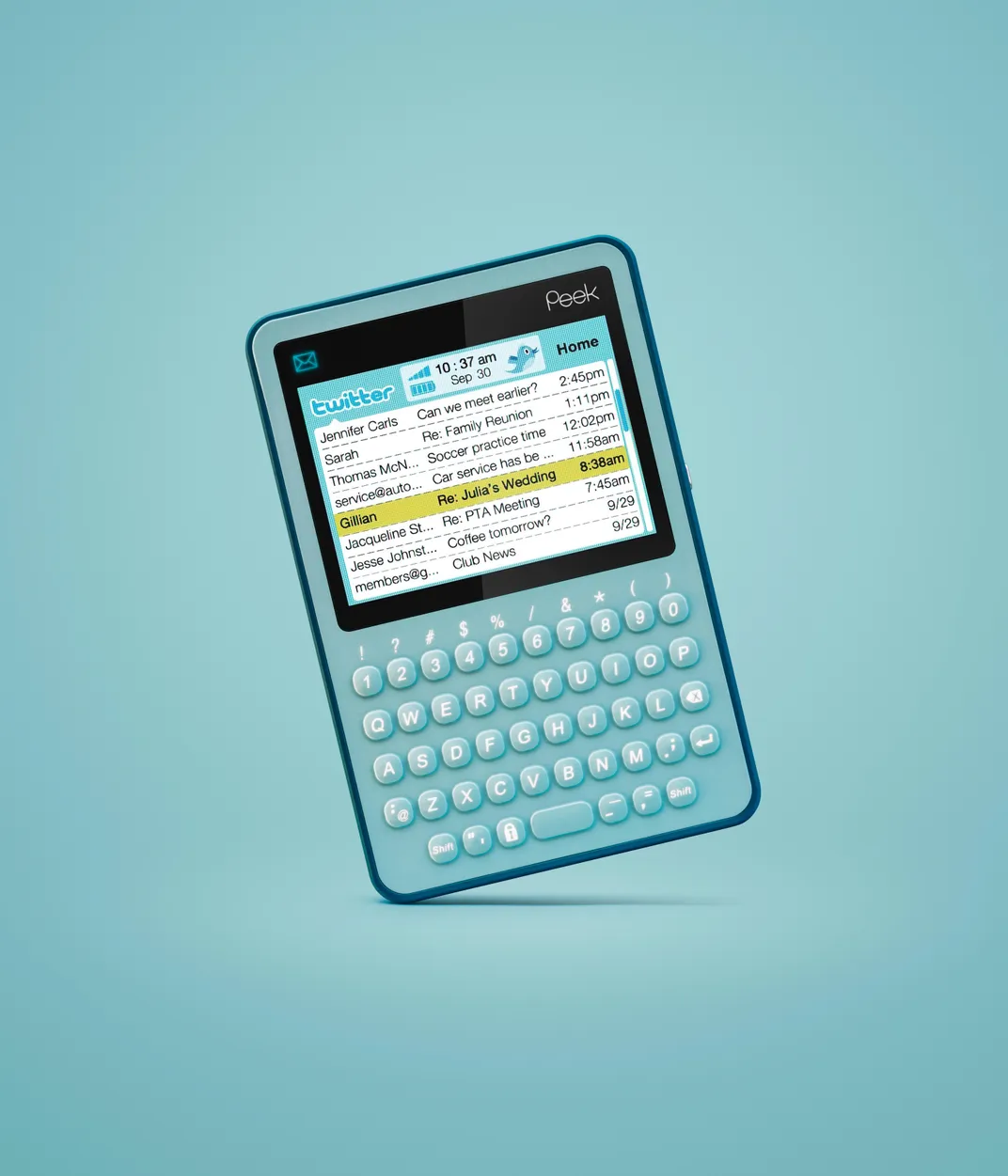

Ill-fated mobile gadgets are amply represented: the short-lived Nokia N-Gage, a telephone and games console hybrid; the Amazon Fire Phone, a smoldering shambles with a maddening hard-sell button; and the legendary TwitterPeek, a $200 stocking stuffer that, though solely dedicated to Twitter, featured a 20-character home screen too small to fit a full, 140-character tweet. And, of course, the wearable computer known as Google Glass, a notoriously faulty attempt to insert the web into a pair of spectacles.

Then there’s Bic for Her, an embossed ballpoint in pink and lavender that promised a “soft, pearlescent grip for all-day comfort.” The so-called lady pen, discontinued in 2016, was immortalized in sardonic reviews on the Amazon website. “I bought these for a woman at work as she couldn’t figure out how to use a man’s pen,’’ one purchaser, presumably a sardonic male, reported. “After I helped her open the package, she was super-happy.” One super-happy female wrote: “I gave these to all of the men in my office, and they all received pay cuts a few weeks later!”

For sheer shock value, nothing tops the infamous Rejuvenique beauty mask. When strapped to the face for 15-minute intervals, the contraption allegedly toned skin and reduced wrinkles by transmitting mild electric impulses to all 12 of the wearer’s “facial zones.” Powered by a nine-volt battery and endorsed by “Dynasty” star Linda Evans, Rejuvenique looked like the ice hockey mask worn by the teen-stalking psycho in Friday the 13th.

The novelties showcased in the museum all tanked for different reasons: some due to price or poor design (a replica of the Edsel, a 1958 car model with a grille that “looked like an Oldsmobile sucking a lemon”), some because management feared a product would never take off (Kodak’s digital camera, patented in 1978), some due to hubris (Harley-Davidson’s brand extension Hot Road, an eau de toilette for men who wanted to smell like a chopper) and some because they didn’t live up to the hype (the Segway, a two-wheeled, self-balancing scooter). “When it appeared in 2001, the Segway was supposed to revolutionize public transport,” West says. “Today it’s used by mall cops and tourists before they go get drunk.”

He allows that his inclusions and exclusions are subject to debate—which in itself makes the museum interesting. A man with multiple sclerosis emailed West to protest the presence of the Segway: “It is my legs and has reopened everyday life so that I might enjoy social interaction with others, be it shopping, art at a museum, music at a concert, nature at a park, family. It has given me both normalcy and dignity.” West acknowledges that failure is contextual—personal or humanitarian success may coincide with a commercial misfire.

A onetime “innovation researcher” at Sweden’s Lund University, the 43-year-old West holds a doctorate in organizational psychology and counsels corporations on how to achieve success by embracing failure. “Failure is something to be celebrated,” he says. “It’s a natural and essential part of innovation.” He invokes a quote attributed to the media executive Jon Sinclair: Failure is a bruise, not a tattoo. “Failing hurts and it may not look good,” reasons West, “but it will pass.”

He may as well be describing the Apple Newton MessagePad, a bulky hand-held gizmo from 1993 touted as the first personal digital assistant with handwriting recognition. Though the unreliable Newton went belly up almost immediately, it’s now regarded as the great-great-granddad of the iPhone. West notes that in Silicon Valley, failure is often viewed as “heroic and instructive.” Indeed, Dave McClure, co-founder of the 500 Startups incubator for tech ventures, once said that he seriously considered naming the company Fail Factory: “We’re here trying to ‘manufacture fail’ on a regular basis, and we think that’s how you learn.” (In June, McClure resigned as CEO for engaging in what the organization termed “inappropriate interactions with women in the tech community”—a self-manufactured fail if there ever was one.)

The British entrepreneur Richard Branson, whose empire has included hotels, airlines and the world’s first commercial spaceline, recently tweeted a line about failing from Samuel Beckett’s prose piece Worstward Ho: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail Better.” Ironically, the phrase was intended not as a motivational motto but an exhortation to keep failing until you fail completely—or die trying. A few lines later, Beckett added: “Fail again. Better again. Or better worse. Fail worse again. Still worse again. Till sick for good. Throw up for good.”

Silicon Valley venture capitalist Geoff Lewis is equally skeptical of celebrating real failures. Mindful of all the employees who have been laid off or relegated to dead-end assignments due to executive product bungling, Lewis says he’d “like to see the pendulum swing back a bit toward fear. Toward something one can rebound from, something to be neither embellished nor marginalized, but rather something to be mourned and then moved on from: plainly, a tragedy.”

West isn’t quite so gloomy. “The message I want to convey is that it’s OK to share your unrefined ideas, your stupid questions, your failures without then being negatively judged.”

It’s fitting that his museum was launched in Sweden, birthplace of the Vasa, perhaps the most epic technological fail of the 17th century. The hull of the lavishly appointed frigate was 226 feet long, 38.5 feet wide and rose to 63 feet high at the stern. Those specifications contained a fatal design flaw: The upperworks of the hull were too tall and heavily built for the relatively small amount of hull below the waterline. The ship’s five decks were designed to carry a complement of 133 seamen and 300 soldiers; among its 64 cannons were 48 massive bronze 24-pounders. All of which made the vessel dangerously unsteady. Just minutes into the Vasa’s maiden voyage the wind picked up in Stockholm Harbor and, lacking the ballast to counterweight the heavy artillery, the ship heeled until water rushed in through its open gun ports. Having traveled less than a mile, the world’s latest weapon of mass destruction turned turtle and sank. A scale model of the Vasa was on view at the Museum of Failure’s first home in the Swedish port city of Helsingborg.

West, for his part, would direct visitors to a tiny “confession booth” and ask them to jot down their greatest failures on index cards, which were then posted on a wall. One card read: “I crashed my car driving to the Museum of Failure.” West’s own biggest flub? “When I bought the internet domain name, I accidentally misspelled ‘museum.’”

High overhead and difficulty finding a permanent space caused him to close shop in Helsingborg in September. Fortunately, the city stepped in and offered the museum a home in its cultural center. The April reopening will include exhibits that highlight failed social and nonprofit innovations. West savors the irony of the exhibition’s initial stumble. “I should put the Museum of Failure on display at its own museum.”

Editor's note: This story originally stated that the Vasa frigate was 398 feet wide. It is 38.5 feet wide.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/26/87/2687de43-761f-4d4e-a109-6a86729196e5/dec2017_c06_prologue.jpg)