Temple Grandin’s Pig-Stunning System Came to Her in a Vision

Patented 20 years ago, the invention never took off. But the renowned animal science professor still thinks its time may come

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/ca/07ca95c8-5762-4cd6-b236-076abcbef7ab/temple_grandin.jpg)

The idea came to Temple Grandin all at once, as a fully formed picture in her head. Ideas often come to her that way.

“I just saw it,” she says. “I’m a total visual thinker. I oftentimes just get these ideas as I’m falling asleep.”

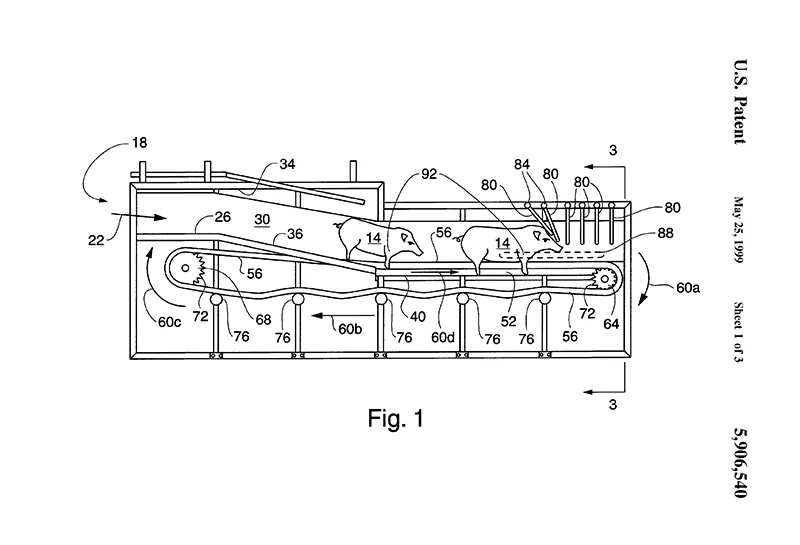

The idea was for a passageway conveying pigs towards a slaughter room, the tunnel hung with overlapping electrodes to continuously stun the animals into unconsciousness. Twenty years ago this May, the vision was awarded a patent.

"The present invention provides the capability for an electrical current sufficient to stun an animal to be applied continuously through a passageway with the electrodes of the series being fixedly attached within the passageway," the patent reads.

Tough it might sound, at first blush, like a torture device, it’s actually meant for the pig’s welfare, to keep it calm before the inevitable. Though there were a number of stunning systems already in use at the time Grandin applied for the patent, they had a number of drawbacks: the pigs had to remain still, the animals would become stressed while being herded into position, and the electrodes had to be precisely positioned or the stunning would be ineffective.

“Electrical stunning when you do it now it's instantaneous, it’s like you turn off the lights,” Grandin says. “The pig is not going to feel anything.”

Grandin, a professor of animal science at Colorado State University, has uncommon insight into the experience of livestock. As a person with autism, she is deeply familiar with the anxiety of being in an unfamiliar environment. She also understands how small sensory details that might escape most people’s notice can cause fear and panic in cows or pigs. A coat left hanging across a slaughterhouse rail looks scarily like a predator. A sudden noise sparks terror. That insight informs her work designing systems to make livestock handling more comfortable for animals.

“Animals do not think in words,” Grandin says. “The first thing is to get away from verbal language. What does it hear? What does it see? What does it feel? It’s a sensory world.”

Before she was a celebrated scientist with her own HBO biopic (Claire Danes played her in the 2010 film), Grandin was a little girl growing up in Boston in an era before autism was widely understood. Experts said she was brain damaged and recommended institutionalization, but her family kept her at home, working with speech therapists and attending supportive schools.

These experiences drove Grandin to achieve.

“I wanted to prove I wasn’t stupid,” she says.

She went on to earn a doctorate from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, to invent multiple livestock handling technologies, and to write more than a dozen books, including several on the experience of being on the autism spectrum.

Grandin has invented a number of systems for improving livestock handling, including a diagonal pen that takes advantage of cattle's natural instincts in order to herd them towards loading chutes, a system for assessing and scoring animal-handling in meat processing plants, and a number of cattle restraining systems. Her double rail conveyer system for bringing cattle calmly to the slaughterhouse is used to handle half the cattle in America. Her most famous invention is probably her "hug machine," which she created while in college. Inspired by the tight-squeeze pens that calm cattle during innoculations, she built the device for humans, to deliver a sensation of pressure that could soothe anxiety.

The pig-stunning system, officially called “animal stunning system prior to slaughter,” was not, however, one of her successes. It was trialed in a meat processing plant, but it simply couldn't beat the appeal of alternative forms of stunning, Grandin says—though this may be changing.

Animals have been routinely stunned prior to slaughter for more than 100 years, whether with electricity, gas or instruments like bolt guns. Stunning animals with carbon dioxide, which had been used to varying degrees since the late 1800s, began to grow in popularity in the 1970s, as it requires less maintenance and can be done in groups without the animals being restrained. But there are growing questions about whether or not CO2 stunning is humane, as it doesn’t render animals unconscious immediately and may cause pain. In recent years, a number of animal welfare groups have called for it to be abolished. Grandin believes this may mean her invention will ultimately be adopted.

"In reviewing the patent, the one thing that stands out is that the stunning can be performed without the aid of a person," says Jonathan Holt, a professor of animal sciences at North Carolina State University. "I think that is important because you potentially take the error out of stunning, such as a person not stunning them long enough or in the correct location. It is also unique that it has a ceiling, which may discourage hogs from trying to climb upwards to escape."

Grandin has innovation in her blood. Her grandfather, John Coleman Purves, was one of the co-inventors of the flux valve, which became part of airplanes’ autopilot system.

“The flux valve was very simple,” Grandin says. “Three little coils, you just stick it in the wing of the plane.” But simple inventions are actually often more difficult to create than complex ones, she notes. “Simple is not easy to make up,” she says. “It’s something totally different.”

Though the patent on the pig-stunning system has expired, Grandin still hopes to see the technology in action again.

“One thing I’m proud of about the stunner patent is it is truly novel and it does work,” she says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)