Throughout the world, from the humblest abode to the most lavish mansion, our homes have always been a respite from the world. For many of us, our daily lives now upended by quarantine, our homes have suddenly become our world.

When we think of the technology that makes our homebound life bearable, we call to mind those electronic devices that allow us to remain connected to the outside world. However, it might surprise us to know that, for our ancestors, many of the objects we take for granted, like napkins, forks and mattresses, were also once marvels of comfort and technology—available to only the few. Our temperature-controlled homes filled with comfortable furniture and lights that turn on at the flick of a switch are luxuries unfathomable to the kings and queens of the past. Those things that were once only the purview of royalty—chandeliers, comfortable seating, bed pillows—have become such a part of our everyday lives that we forget that all but the basic necessities for survival were once out of reach for all but the upper echelon of society. Our homes are castles beyond what they could have ever imagined.

Perhaps, like me, you’ll find yourself grateful for our ancestors who suffered with stone or wooden headrests, stiff-backed chairs and cold nights before feather-stuffed pillows and fluffy duvets were part of everyday life (and appreciative of those who imagined that things could be better). In The Elements of a Home: Curious Histories Behind Everyday Household Objects, from Pillows to Forks, I’ve uncovered the stories behind the objects that fill our homes and our lives. They all come with stories. What follows are a few of my favorites.

In some homes, fireplaces remained lit for generations.

While contemporary fireplaces are used mostly as a design focal point, for thousands of years the fireplace was a necessary source of both heat and light. All medieval homes, whether a hut or manor, were built around a simple open hearth—very much like building a campfire in the center of a home (talk about smoke inhalation!). Families throughout Europe would gather around the fireplace to cook and eat, tell stories and sleep. It was so essential to everyday life that the hearth fire was rarely allowed to die out.

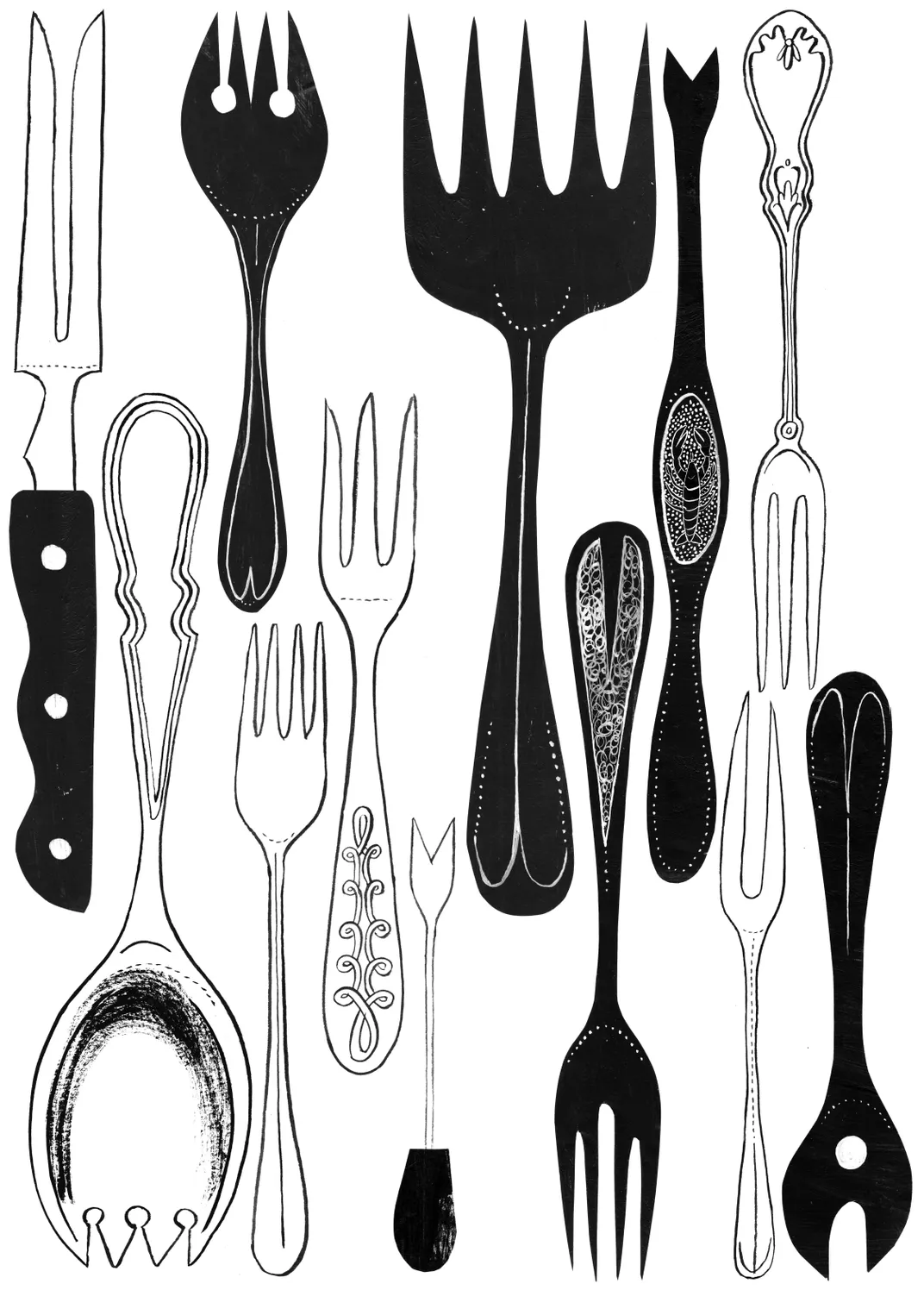

The fork was once considered immoral, unhygienic and a tool of the devil.

In fact, the word "fork" is derived from the Latin furca, which means pitchfork. The first dining forks were used by the ruling class in the Middle East and the Byzantine Empire. In 1004, Maria Argyropoulina, niece of the Byzantine emperors Basil II and Constantine VIII, was married to the son of the Doge of Venice. She brought with her a little case of two-pronged golden forks, which she used at her wedding feast. The Venetians were shocked, and when Maria died three years later of the plague, Saint Peter Damian proclaimed it was God’s punishment. And with that, Saint Peter Damian closed the book on the fork in Europe for the next four hundred years.

The chopstick predates the fork by about 4,500 years.

The ones you encounter with the most regularity might be waribashi, disposable chopsticks made of cheap wood found at many Japanese and Chinese restaurants. These aren’t a modern invention. Waribashi were used in the first Japanese restaurants in the 18th century. There is a Shinto belief that something that has been in another’s mouth picks up aspects of their personality; therefore, you did not share chopsticks, even if they had been washed.

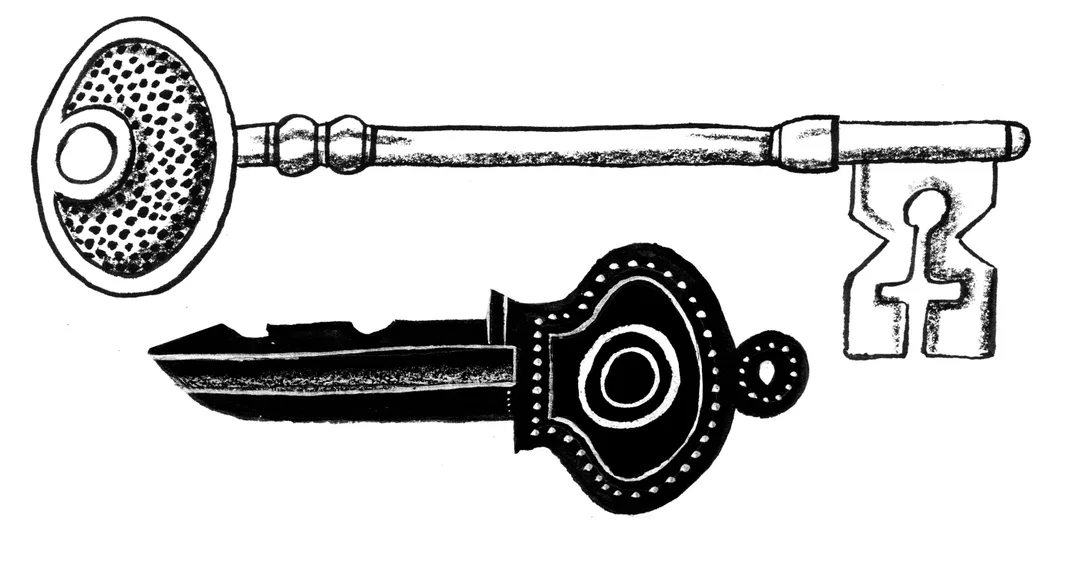

Keys weren’t always pocket-sized.

The greatest luxury is not high thread count sheets or the quality of your crystal, it’s the feeling of security and sanctuary that comes when you click the lock to the door of your home closed behind you. However, the ones that opened the wooden locks of the massive marble and bronze doors of the Greek and Egyptians could be three-feet in length, and so heavy that they were commonly carried slung over the shoulder—a fact that is mentioned in the Bible. The prophet Isaiah proclaimed, “And the key of the house of David will lay upon his shoulder.”

Ancient Romans, who lived extravagantly in most other aspects of their lives, were surprisingly spartan when it came to their bedrooms.

The poor slept on a straw mattress set in a simple wooden frame. If your purse allowed, the frame was cast in bronze or even silver, topped with a mattress stuffed with wool or down. The bed—and only the bed—resided in a room called a cubiculum (from which we get the word cubicle), a small space with tiny windows that let in little light.

The first proto-napkins were lumps of dough called apomagdalie.

Used by the Spartans—those residents of the military powerhouse city in ancient Greece—the dough was cut into small pieces that were rolled and kneaded at the table, deftly cleaning oily fingers and then thrown to the dogs at the meal’s end. Eventually, raw dough became cooked dough, or bread. Since there weren’t any utensils on the Greek table, bread also served as both spoon and fork (the food would have been cut into bite-size pieces in the kitchen) so using bread to discreetly keep your fingers clean before taking a smear of hummus wasn’t just delicious, it was convenient.

Plates were once made out of bread.

If you’ve ever slurped clam chowder out of a bread bowl, then you’ll appreciate the medieval trencher. These “plates,” used throughout Europe and the United Kingdom, were cut from large round loaves of whole wheat bread that were aged for four days, then sliced into two three-inch rounds. Partygoers would rarely eat the trencher; once supper was finished, those that were still in one piece were given to the destitute, or thrown to the dogs.

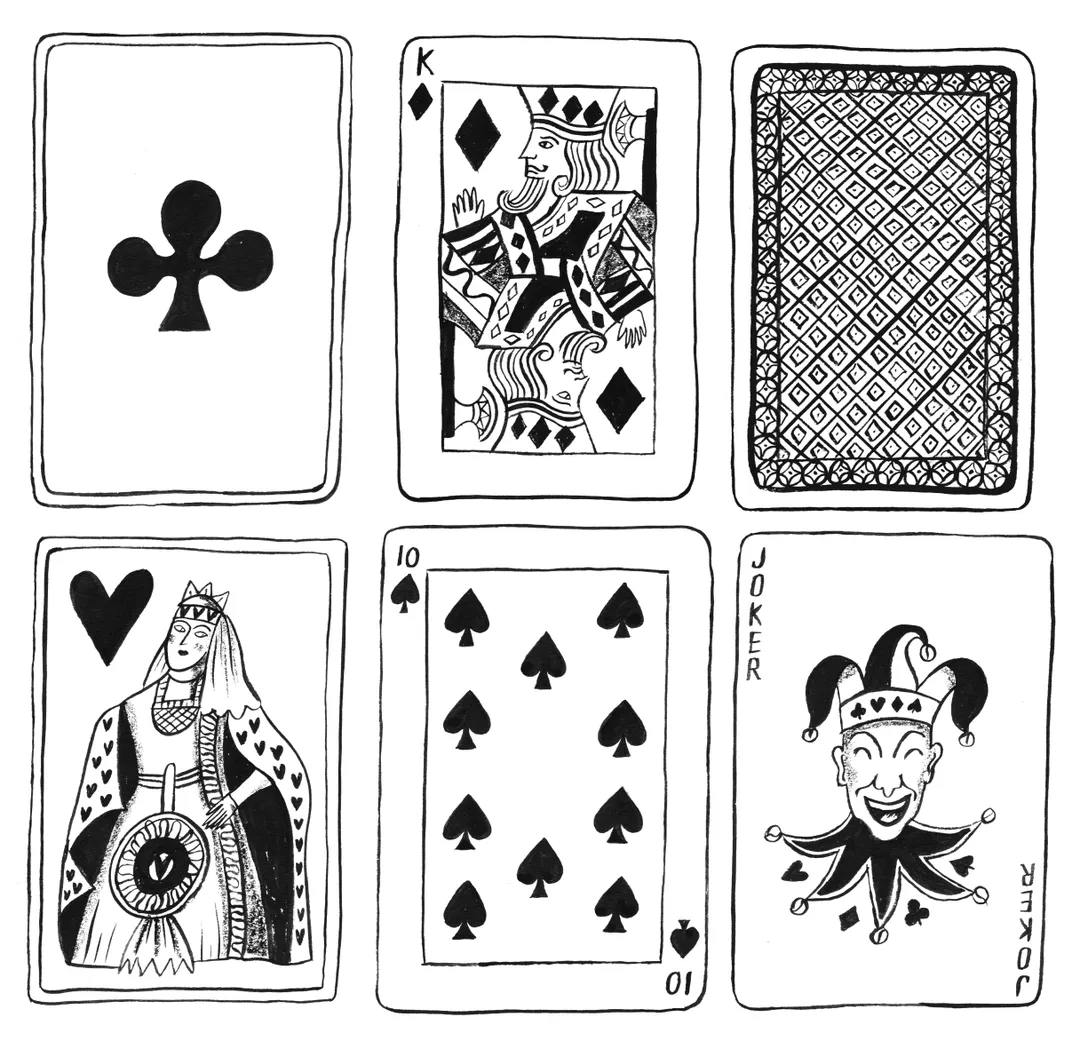

Playing cards came from the only nation with the paper-making technology to pull it off: China.

The first known cards, developed in the ninth century A.D. were the size of dominoes. In China, card games became popular as an activity that was good for the mind—meditative, yet challenging, as well as social. In 969 A.D., when Emperor Muzong of Liao capped off a 25-day drinking binge by playing cards with his empress, it’s doubtful he had any idea that his favorite pastime would travel the Silk Road through India and Persia before igniting a frenzy for the game in Europe.

In Ancient Egypt, pillows were more like small pieces of furniture than stuffed cushions.

For those of us who spend half the night folding, turning or fluffing our pillows in an effort to find the perfect sleep position, it’s difficult to imagine that softness hasn’t always been a priority. For many living in ancient Africa, Asia and Oceania, pillows were stiffer than the stuffed cushions we have come to rely on for a good night’s sleep. These early pillows, some dating as far back as the Third Dynasty (around 2707-2369 B.C.E.) look a bit like child-sized stools with a curved piece resting upon a pillar. These stands supported the neck, not the head, perhaps to safeguard the elaborate hairdos that were en vogue.

Eating on a bare table was once something only a peasant would do.

Medieval diners would be horrified at our casual attitude toward table linens. For knights and their ladies, good linen was a sign of good breeding. If you could afford it (and maybe even if you couldn’t), the table would be covered by a white tablecloth, pleated for a little extra oompf. A colored cloth was thought to impair the appetite. (The exception to the white-only rule was in rural areas where the top cloth might be woven with colorful stripes, plaids or checks.) Diners sat along one side of the table and the tablecloth hung to the floor only on that side to protect guests from drafts and keep the animals from walking over their feet.

The Elements of a Home

The Elements of a Home reveals the fascinating stories behind more than 60 everyday household objects and furnishings. Brimming with amusing anecdotes and absorbing trivia, this captivating collection is a treasure trove of curiosities.

Amy Azzarito is a writer, a design historian, and an expert on decorative arts. Her design work has been featured in a wide range of publications, including the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Whole Living magazine, the Wall Street Journal, Architectural Digest and Design Milk. Chronicle Books just released her new book, The Elements of a Home.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/c3/22c3a85b-85e8-4748-8f14-ee3c0b6fd479/elements_of_a_home-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/a1/9aa1d250-13de-4590-b1e1-b00e33ea22b8/elements_of_a_home_header.jpg)