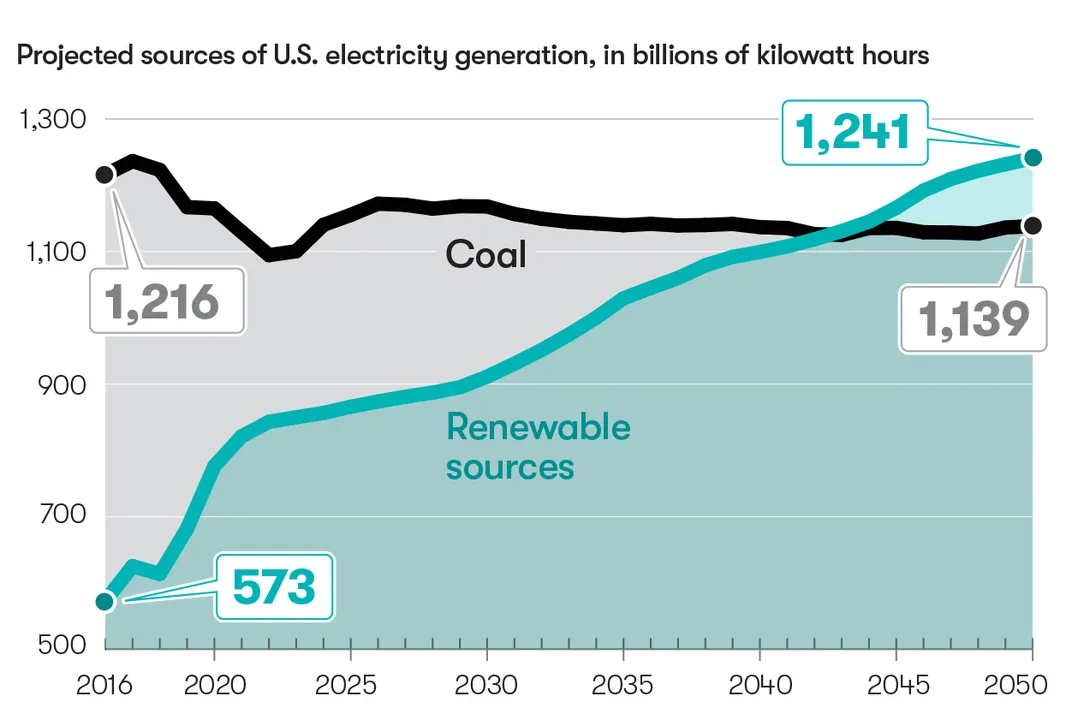

Is a Texas Town the Future of Renewable Energy?

A high-wattage Republican Mayor of Georgetown, Texas, has become the unlikeliest hero of the green revolution

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/53/30538c3b-1594-4502-9441-a7d5104cfd6f/apr2018_d01_futureofenergy.jpg)

Dale Ross, the mayor of Georgetown, Texas, has a big smile, a big handshake and a big personality. In last year’s election, he won big, with 72 percent of the vote. The key to his success? “Without being too self-reflective,” he says, “I just like people.” He’s a Republican, and his priorities are party staples: go light on regulation, be tough on crime, keep taxes low. But the thing that is winning him international renown is straight out of the liberal playbook—green power. Thanks to his (big) advocacy, Georgetown (pop. 67,000) last year became the largest city in the United States to be powered entirely by renewable energy.

Previously, the largest U.S. city fully powered by renewables was Burlington, Vermont (pop. 42,000), home to Senator Bernie Sanders, the jam band Phish and the original Ben & Jerry’s. Georgetown’s feat is all the more dramatic because it demolishes the notion that sustainability is synonymous with socialism and GMO-free ice cream. “You think of climate change and renewable energy, from a political standpoint, on the left-hand side of the spectrum, and what I’ve done is toss all those partisan political thoughts aside,” Ross says. “We’re doing this because it’s good for our citizens. Cheaper electricity is better. Clean energy is better than fossil fuels.”

In a twist that has some Republicans in this oil- and gas-rich state whistling Dixie, Ross is now friends with Al Gore, who featured Ross in An Inconvenient Sequel, the 2017 follow-up to An Inconvenient Truth, his Oscar-winning documentary about global warming. “We bonded right away,” Ross recalls. “I said, ‘Mr. Vice President, we’ve got a lot in common. You invented the internet. I invented green energy.’” Trained as an accountant, Ross still works as one—being mayor of Georgetown is a part-time job—and there’s no mistaking his zeal for the other kind of green. When conservatives complain about his energy politics, he is quick to remind them that the city has the lowest effective tax rate in Central Texas.

With Georgetown emerging as a brave new model for a renewable city, it makes sense to ask if others can achieve the same magical balance of more power, less pollution and lower costs. In fact, cities ranging from Orlando to St. Louis to San Francisco to Portland, Oregon, have pledged to run entirely on renewable energy. Those places are much larger than Georgetown, of course, and no one would expect misty Portland to power a light bulb for long with solar energy, which is crucial to Georgetown’s success. But beyond its modest size, abundant sunshine and archetype-busting mayor, Georgetown has another edge, one that’s connected to a cherished Lone Star ideal: freedom.

**********

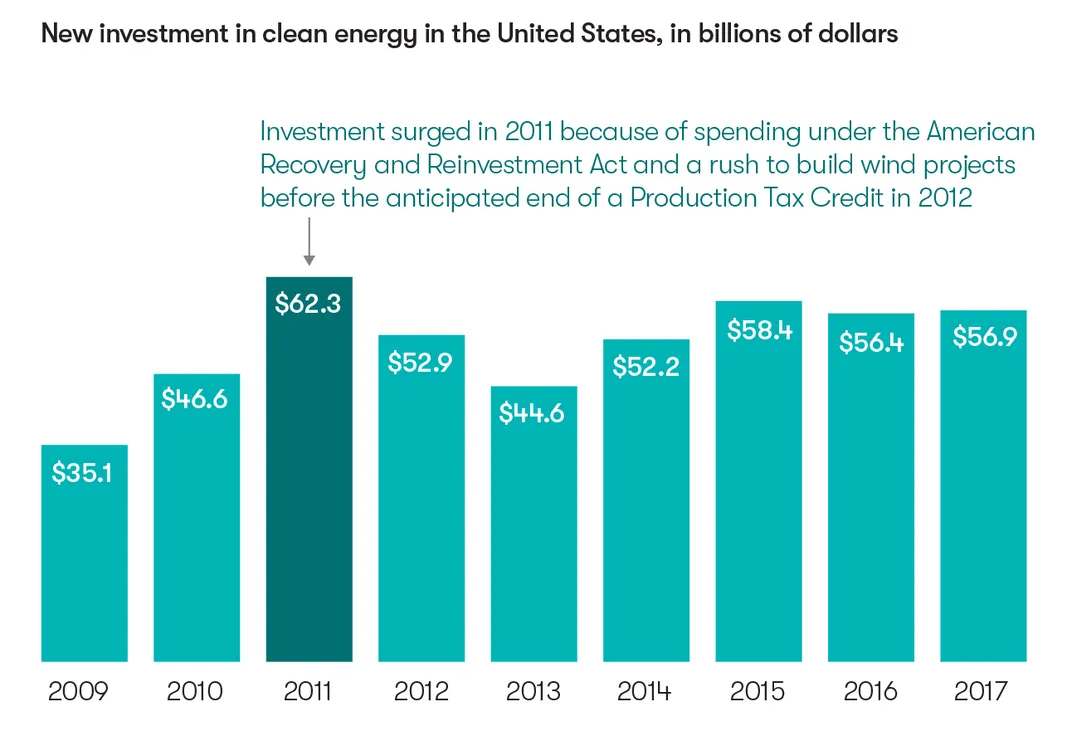

America is embracing renewables, slowly. In 2016, Massachusetts passed a law promoting a huge investment in wind and hydropower; the first megawatt is expected to hit the grid in 2020. Early this year New York State announced plans to spend 12 years building the infrastructure for a $6 billion offshore wind power industry. Hawaii has pledged to be powered entirely by renewable energy—in 2045. Atlanta’s goal is 2035 and San Francisco’s is 2030. Typically, plans to convert to sustainable energy stretch on for decades.

Georgetown made the switch in less than two years.

Ross, something of a libertarian at heart, entered politics because he was ticked off that the municipal code prohibited him from paving the driveway to his historic home entirely in period-appropriate brick. (The code required some concrete.) He joined the city council in 2008 and was elected to his first term as mayor in 2014. He often likens the city to “Mayberry R.F.D.,” and it does have a town square with a courthouse, a coffee shop where you’re bound to run into people you know and a swimming hole. But it also has Southwestern University, and in 2010 university officials, following a student initiative, told the city council they wanted their electricity to come from renewable sources. The city had already set a goal of getting 30 percent of its power that way, but now, Ross and his colleagues saw their opportunity.

Taken together, the generation and distribution of electric power in the United States is an astonishingly complex undertaking. Utilities may generate their own power or buy it from other utilities; that power travels over a grid of transformers and high- and low-voltage lines to your house. Ownership of utilities varies from nonprofits to cooperatives to for-profits. Federal regulators ultimately oversee the grid. Amazingly, when you flip a switch, electricity is there.

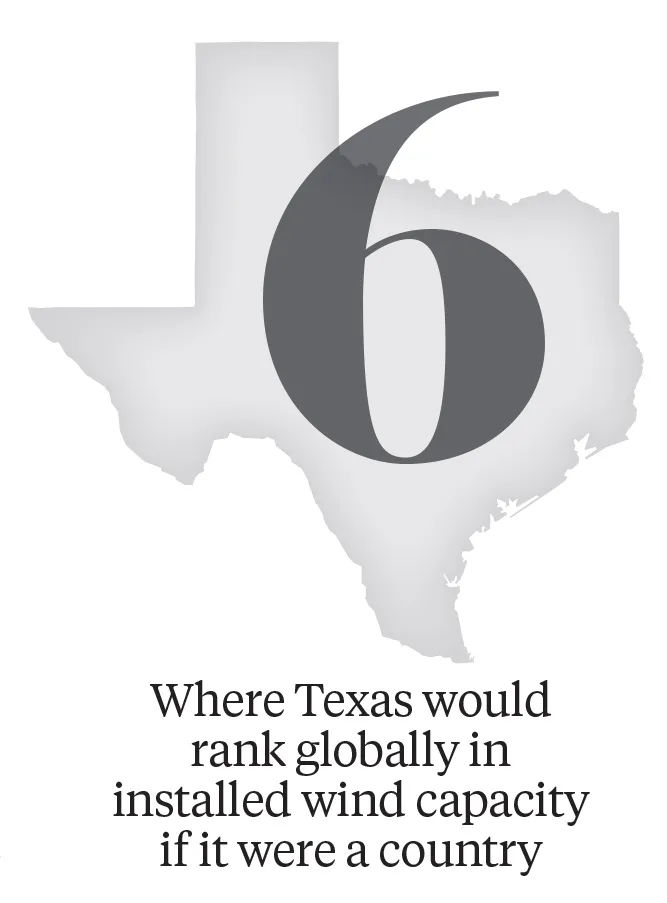

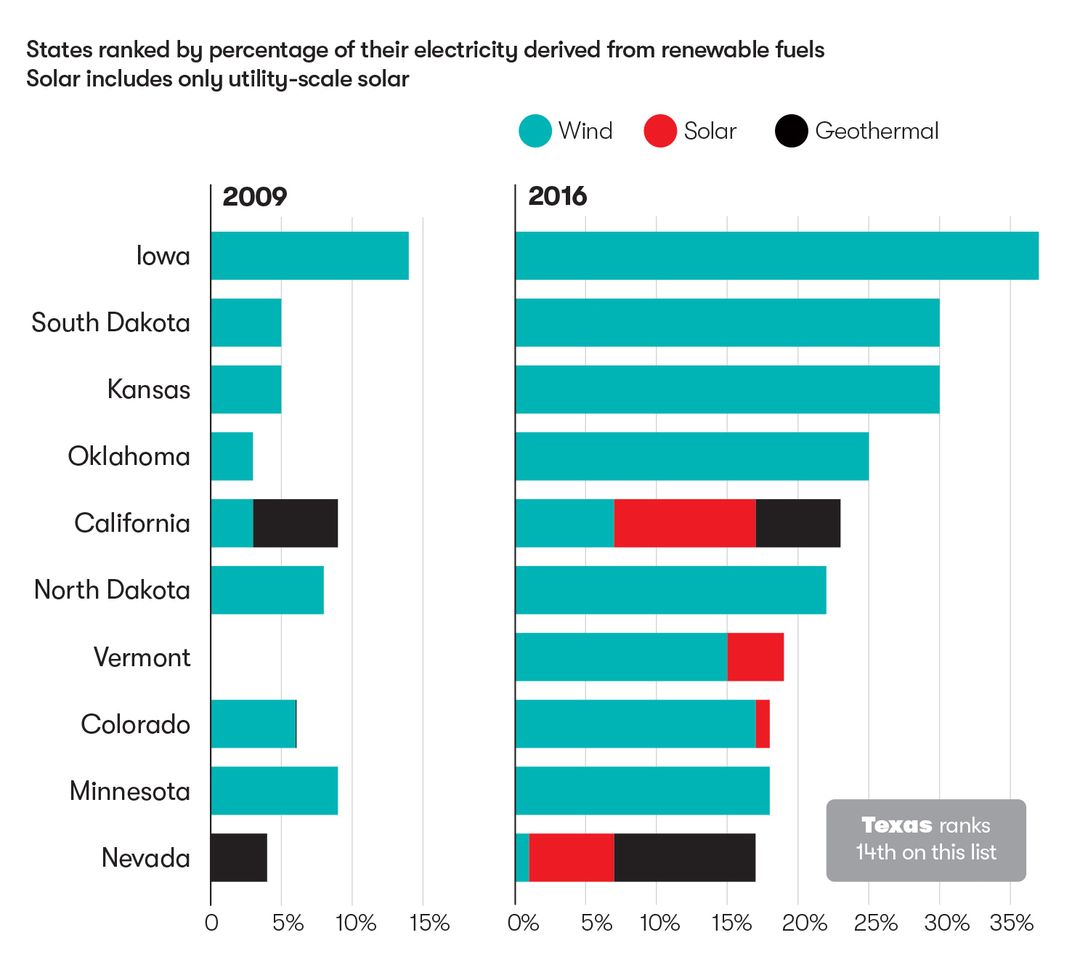

In Texas, the top energy sources had long been coal, natural gas and nuclear. But, perhaps surprisingly, the Lone Star State also leads the nation in wind power; capacity doubled between 2010 and 2017, surpassing nuclear and coal and now accounting for nearly a quarter of all the wind energy in the United States. Solar production has been increasing, too. By the end of last year, Texas ranked ninth in the nation on that front.

Which is to say that Ross and his co-workers had options. And the city was free to take advantage of them because of a rather unusual arrangement: Georgetown itself owns the utility company that serves the city. So officials there, unlike those in most cities, were free to negotiate with suppliers. When they learned that rates for wind power could be guaranteed for 20 years and solar for 25 years, but natural gas for only seven years, the choice, Ross says, was a “no-brainer.”

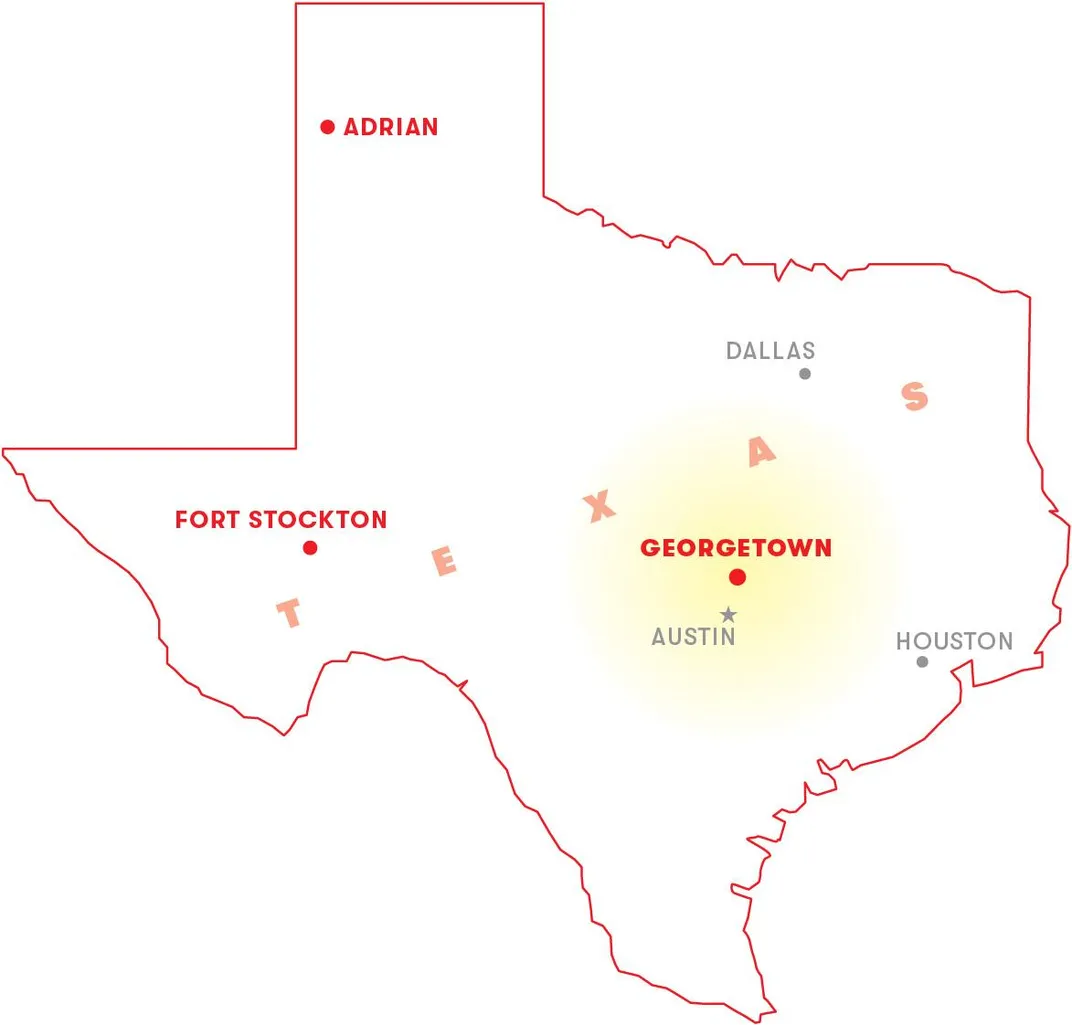

In 2016, the city bought its way out of a contract providing energy derived from fossil fuels and arranged to get its power from a 97-unit windfarm in Adrian, Texas, about 500 miles away in the Texas Panhandle. Georgetown doesn’t own the farm, but its agreement allowed the owners to get the financing to build it. This spring, Georgetown is adding power from a 154-megawatt solar farm being built by NRG Energy in Fort Stockton, 340 miles to the west of the city.

Capture the Sun, Harness the Wind

The outlook for renewable energy used to be dim. now, thanks to better technologies, it’s incandescent.

Even with plans to grow as much as 80 percent over the next five years, the city expects to have plenty of energy from these renewable sources. (To be sure, about 2 percent of the time, the Georgetown utility draws electricity derived from fossil fuels. Ross says the city more than compensates at other times by selling excess renewable energy back to the grid—at a profit.)

Other cities won’t have it so easy. Take Atlanta. Residents buy energy from Georgia Power, which is owned by investors. As things stand, Atlantans have no control over how their power is generated, though that may change. In 2019, Georgia Power, by state law, has to update its energy plan. Ted Terry, director of the Georgia chapter of the Sierra Club, says the nonprofit is working with Atlanta officials to incorporate renewables, primarily solar, into the state’s plan. Developing such energy sources on a scale that can power a metro area with 5.8 million people, as in Atlanta, or 7.68 million in the San Francisco Bay Area, or 3.3 million in San Diego, will prove challenging. But it doesn’t seem impossible. In 2015, California set a goal of deriving 50 percent of its energy from renewable sources by 2030. Its three investor-owned utilities—Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric—are poised to achieve that goal just two years from now, or ten years early.

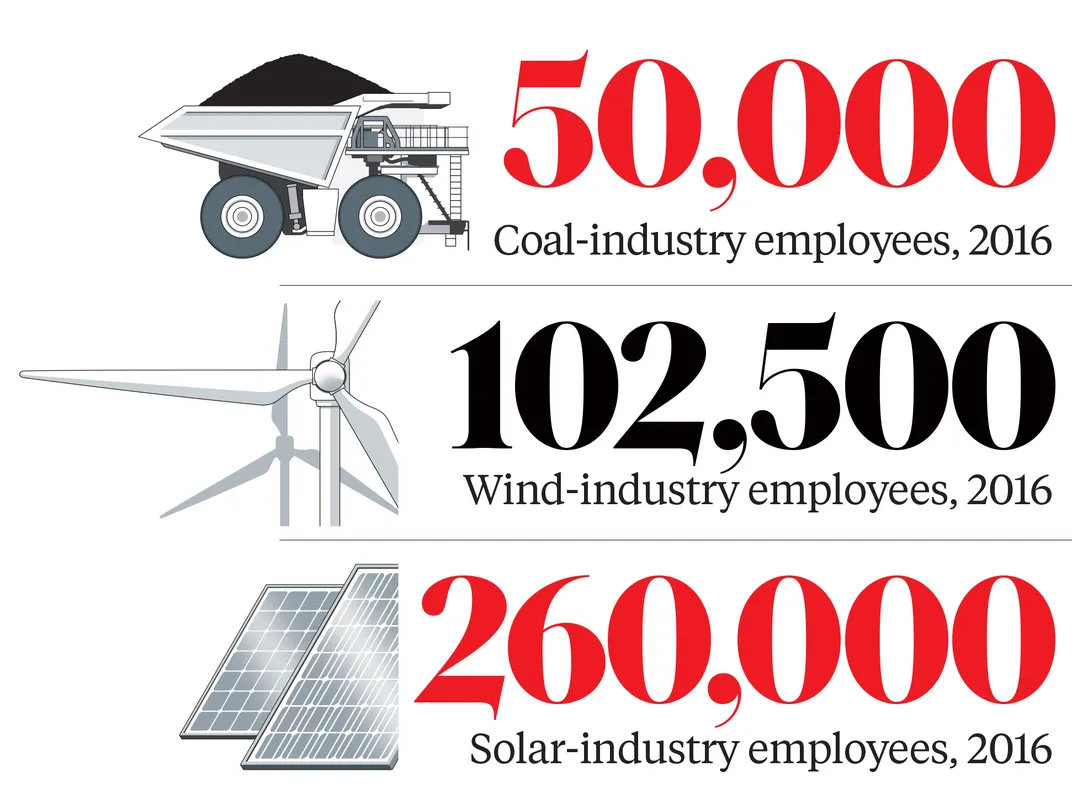

Al Gore says the reason is innovation. “The cost-reduction curve that came to technologies like computers, smartphones and flat-panel televisions has come to solar energy, wind energy and battery storage,” he says. “I remember being startled decades ago when people first started to explain to me that the cost of computing was being cut in half every 18 to 24 months. And now this dramatic economic change has begun to utterly transform the electricity markets.”

Adam Schultz, a senior policy analyst for the Oregon Department of Energy, says he’s more encouraged than ever about the prospects for renewables. Because the Pacific Northwest features large-scale hydropower plants built as part of the New Deal, energy already tends to be less expensive there than the U.S. average. But solar and wind power have “gotten cheaper over the last couple years to the point that I can’t even tell you what the costs are because costs have been dropping so rapidly,” Schultz says. “We have enough sunshine,” he says (presumably referring to the eastern part of the state), “so it’s just a matter of time.”

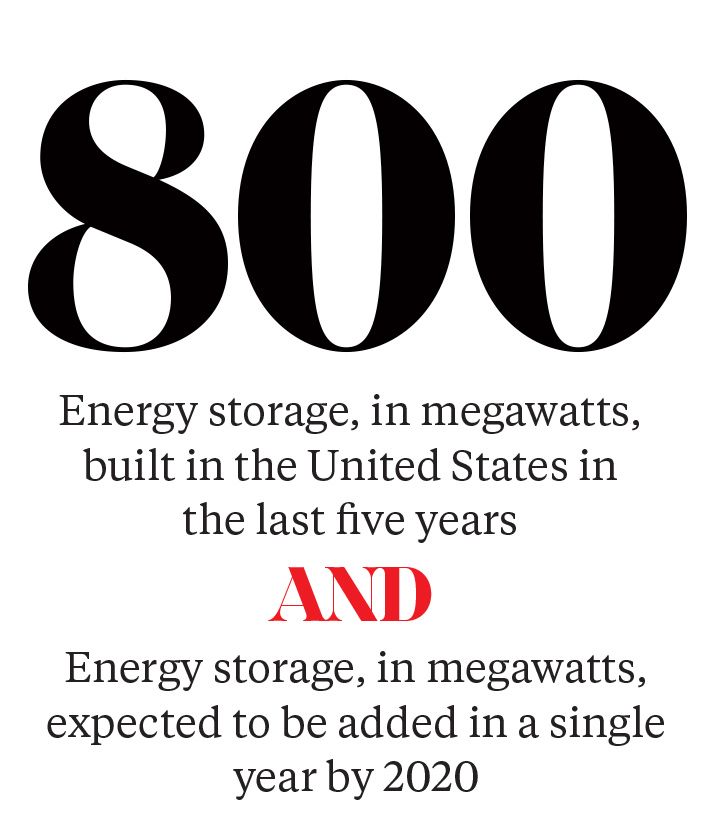

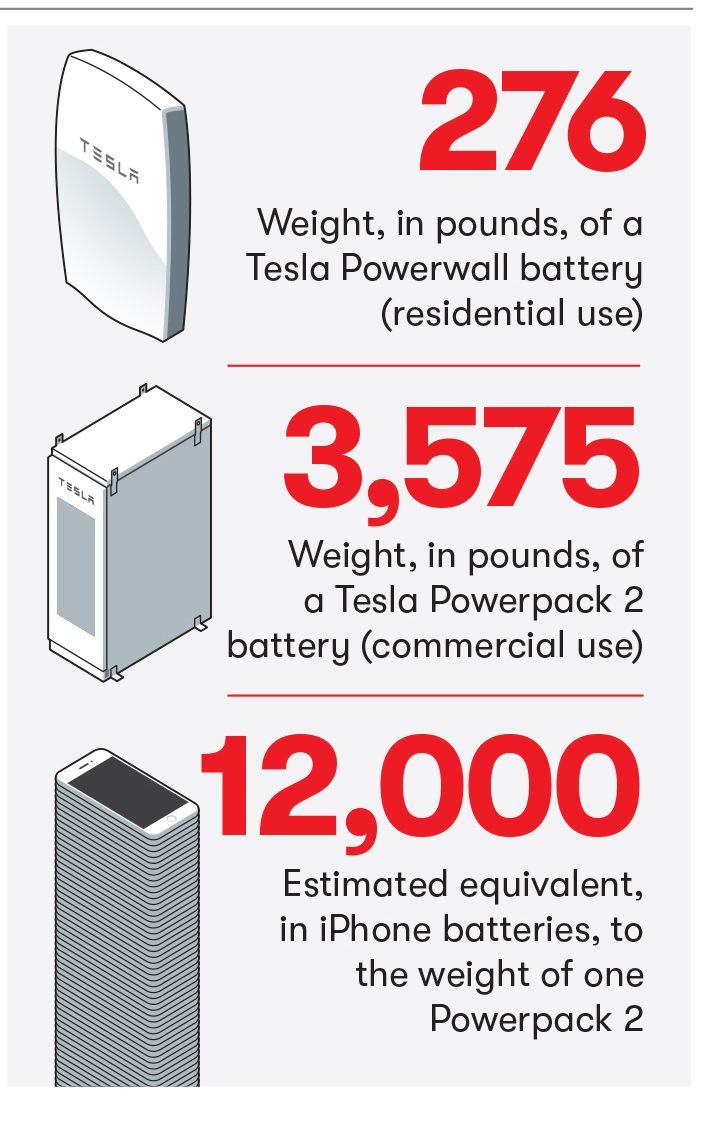

Because one obstacle to adopting wind and solar power is reliability—what happens on calm, cloudy days?—recent improvements in energy-storage technology, a.k.a. batteries, are helping accelerate adoption of renewables. Last May, for example, Tucson Electric Power signed a deal for solar energy with storage, which can mitigate (if not entirely resolve) concerns about how to provide power on gray days. The storage upped the energy cost by $15 per megawatt hour. By the end of the year, the Public Service Company of Colorado had been quoted a storage fee that increased the cost of a megawatt hour by only $3 to $7, a drop of more than 50 percent. In a landmark achievement, Tesla installed the world’s largest lithium-ion battery in South Australia last December, to store wind-generated power. But by then Hyundai Electric was at work in the South Korean metropolis of Ulsan on a battery that was 50 percent bigger.

I ask Ross if he worries about what’ll happen to his city’s power supply if it clouds up over Fort Stockton. He chuckles. “In West Texas, cloudy?” he says. “Really?”

**********

In 2015, Ross wrote an op-ed for Time magazine about his city’s planned transition to renewables. “A town in the middle of a state that recently sported oil derricks on its license plates may not be where you’d expect to see leaders move to clean solar and wind generation,” he wrote. Lest readers get the wrong idea, he felt compelled to explain: “No, environmental zealots have not taken over City Council.”

A little over a year later, Al Gore, one of the nation’s prouder enviromental zealots, showed up in Georgetown with a film crew to interview Ross for An Inconvenient Sequel. In the film, when a reporter asks the former vice president whether Georgetown is a trailblazer for cities of similar size, he says, “Definitely.”

I ask Gore about the lessons he takes from Georgetown. “I think it’s important to pay attention to a CPA who becomes a mayor and takes an objective look at how he can save money for the citizens of his community, even if it means ignoring ideological presuppositions about fossil energy. Especially when the mayor in question is in the heart of oil and gas country.”

Ross is now an energy celebrity, sitting on conference panels and lending Georgetown’s cachet to environmental-film screenings. And it isn’t only conservatives who buttonhole him. As if to prove the adage that no good deed goes unpunished, he also hears from people who worry about the impact of renewables. “They’ll come up to me and say with a straight face, ‘You know what? Those windmills are killing birds,’ ” Ross says. “ ‘Oh, really? I didn’t know that was a big interest of yours, but you know what the number-one killer of birds is in this country? Domestic house cats. Kill about four billion birds a year. You know what the number-two killer of birds is? Buildings they fly into. So you’re suggesting that we outlaw house cats and buildings?’ They go, ‘That's not exactly what I meant.’”

An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power: Your Action Handbook to Learn the Science, Find Your Voice, and Help Solve the Climate Crisis

Where Gore’s first documentary and book took us through the technical aspects of climate change, the second documentary is a gripping, narrative journey that leaves you filled with hope and the urge to take action immediately. This book captures that same essence and is a must-have for everyone who cares deeply about our planet.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.