How Theaster Gates Is Revitalizing Chicago’s South Side, One Vacant Building at a Time

The artist’s creative approach to bringing new life to a crumbling neighborhood offers hope for America’s beleaguered cities

Though celebrated for a dazzling range of achievements—he’s a painter, a sculptor, a performance artist, an academic, an inspirational speaker—Theaster Gates refers to himself as a potter, because that’s how he started, and, after all, it is kind of magical to make something beautiful out of, well, mud. But his newest creative material is unique even by his eclectic standards. It’s a neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago called Greater Grand Crossing, which for the most part isn’t very grand. Weeded lots, two-flat apartments, vacant buildings, crooked frame houses, a median income level almost $20,000 less than the city as a whole. “It’s the place people leave or are stuck [in],” Gates says one day while driving through the neighborhood in his SUV, greeting youths on the sidewalks. They wave back. They recognize him and get what he’s doing: pioneering a new approach to revitalizing a forsaken neighborhood, transforming it without displacing residents or changing its essential character.

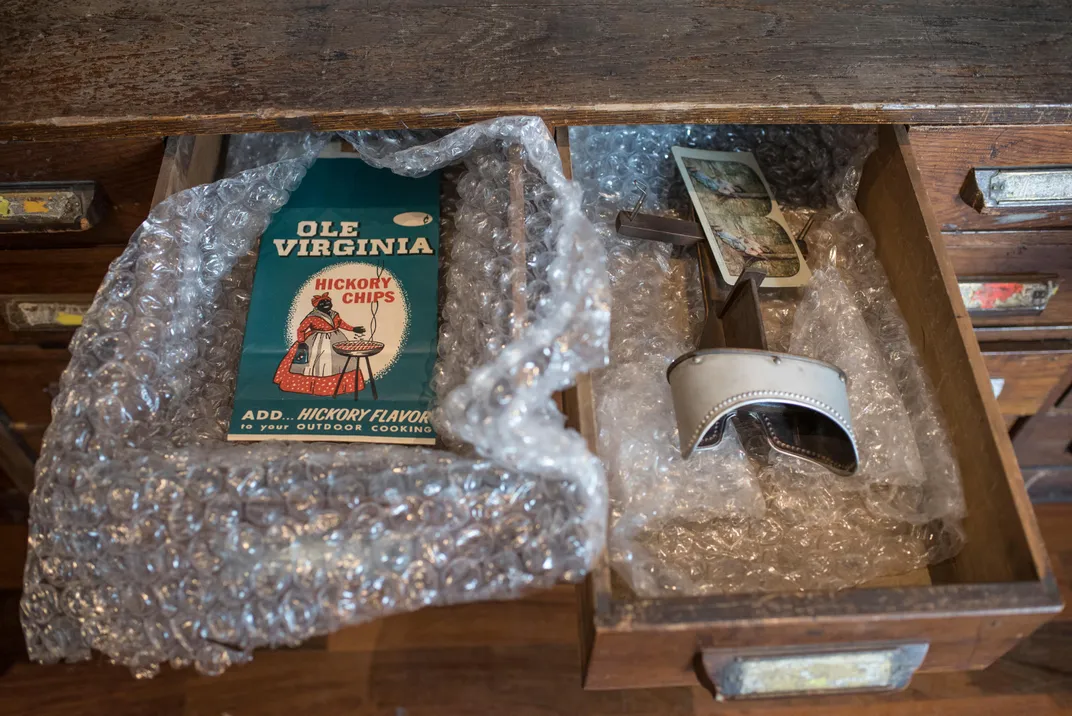

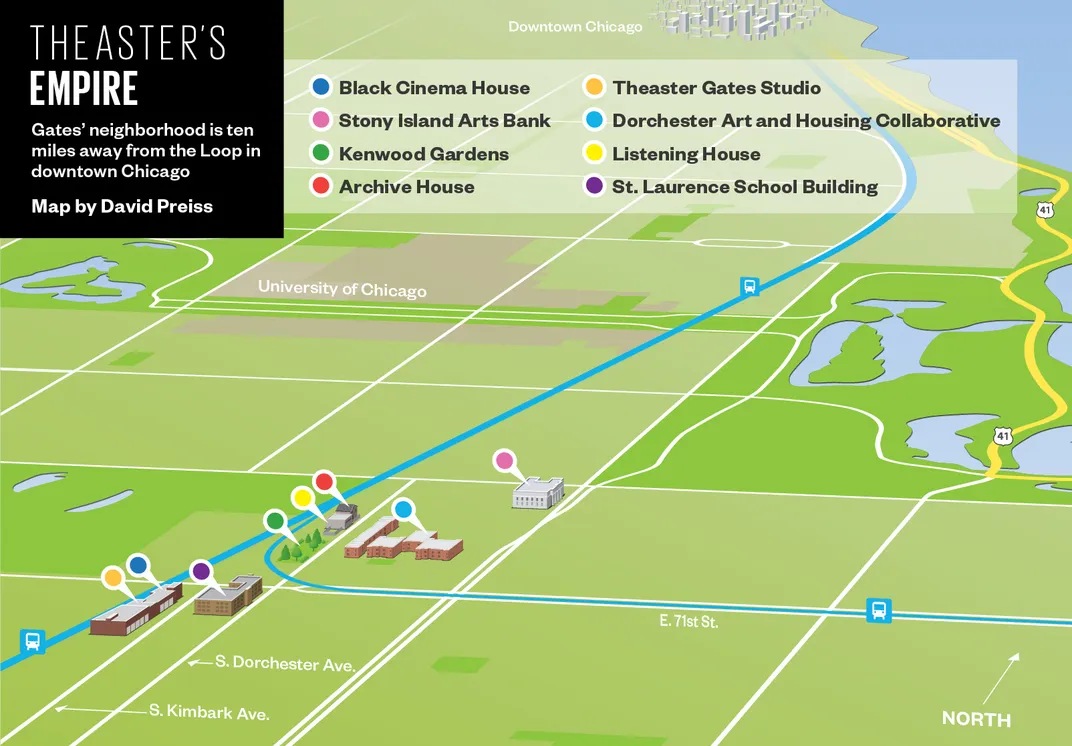

Consider the Stony Island Arts Bank, which opened in October to adoring reviews. Gates bought the dilapidated neo-Classical building, formerly the Stony Island Trust & Savings Bank, from the city for $1 in 2013. It had several feet of standing water in the basement. Undeterred, Gates sold “bank bonds” of salvaged marble for $5,000 each to fund the renovation. Now the space is agleam with a ground-floor atrium and a soaring exhibition hall. It’s part library, part community center, part gallery. Among other culturally significant items, it will house the archives of the Johnson Publishing Company, the publisher of Jet and Ebony magazines, vinyl recordings belonging to the house music legend Frankie Knuckles, and a collection of racist relics known as negrobilia. There will be performances, artists-in-residence and possibly even a coffee bar.

Everyone, of course, knows about the need to revive downtrodden urban neighborhoods—what Gates calls the “challenge of blight”—and there are many strategies afoot, such as enticing members of the “creative class” to move in. But Gates’ “redemptive architecture” isn’t about gentrification, or replacing poor people with well-to-do ones. It’s about creating concrete ways for existing residents to feel that culture can thrive where they live, and there is already reason to believe that good things will follow. Mayor Rahm Emanuel calls Gates a “civic treasure.”

Gates, who grew up on Chicago’s beleaguered West Side and holds degrees in urban planning and religion, took his first step toward rehabilitating Greater Grand Crossing in 2006, buying a former candy store for $130,000. “There was no grand ambition. When you root in a place, you start making things better. I wasn’t on some divine mission,” he says. Two years later he bought the building next door for $16,000. That became the Archive House, which houses a micro library. A former crack house was transformed into the Black Cinema House, hosting screenings and discussions about African-American films. Gates has now invested millions in Greater Grand Crossing through a web of enterprises that includes his studio and the nonprofit Rebuild Foundation and his post as director of Arts + Public Life at the University of Chicago.

The work has boosted his stature. ArtReview has dubbed Gates, who is 42, “the poster boy for socially engaged art.” And earlier this year, he won the prestigious Artes Mundi Prize for a religion-themed installation featuring a revolving figure of a goat like those purportedly used by American Freemasons, a bull sculpture used to ward off bad crops in Africa and a video of soul singer Billy Forston singing “Amazing Grace.”Gates has said he wants to turn Greater Grand Crossing into a “miniature Versailles” that would draw visitors from all around. “I want the South Side to look like my friends’ home in Aspen. I want my pocket part to look like Luxembourg.” Chicago is just the start. He’s doing similar work in Gary, Indiana, and St. Louis, advising other would-be urban potters on how to shape what they’ve got into something great.