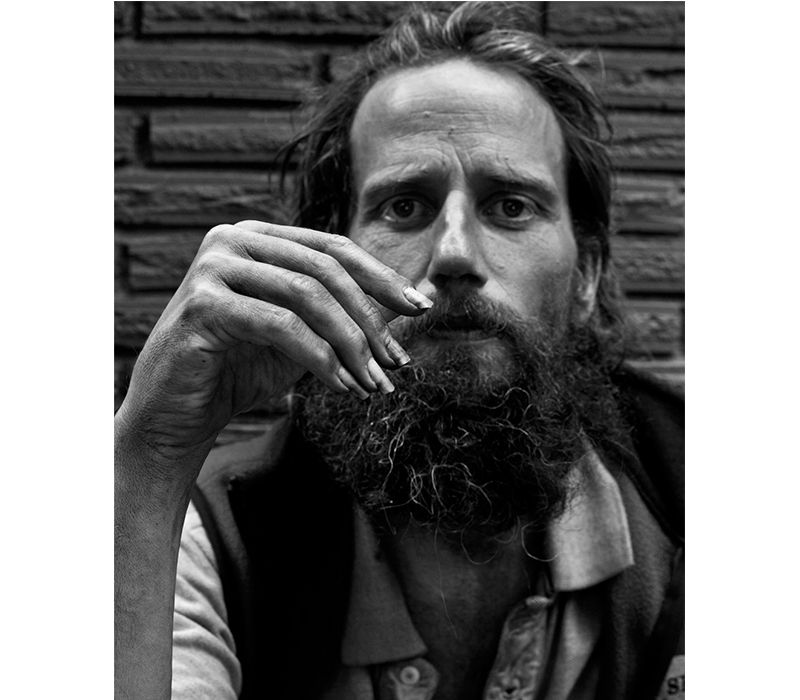

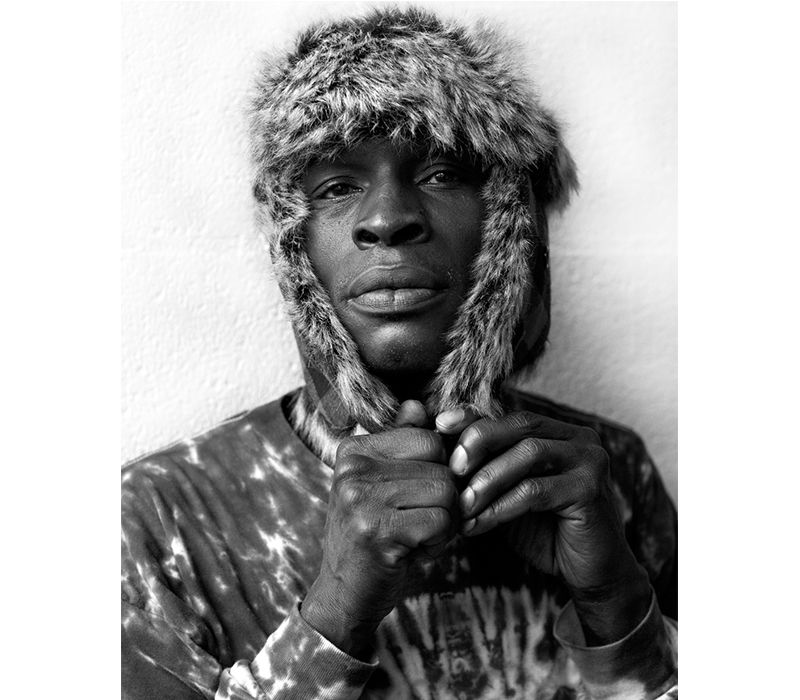

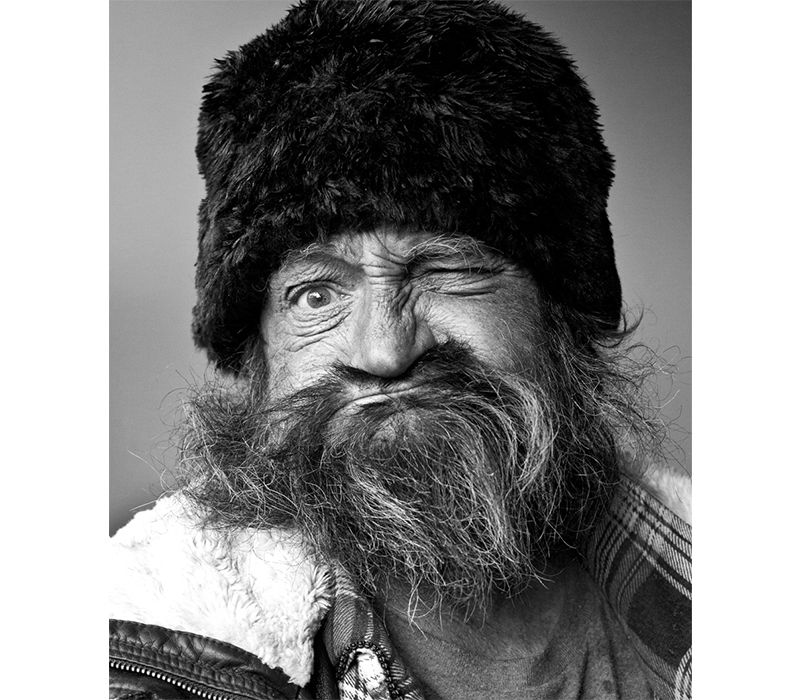

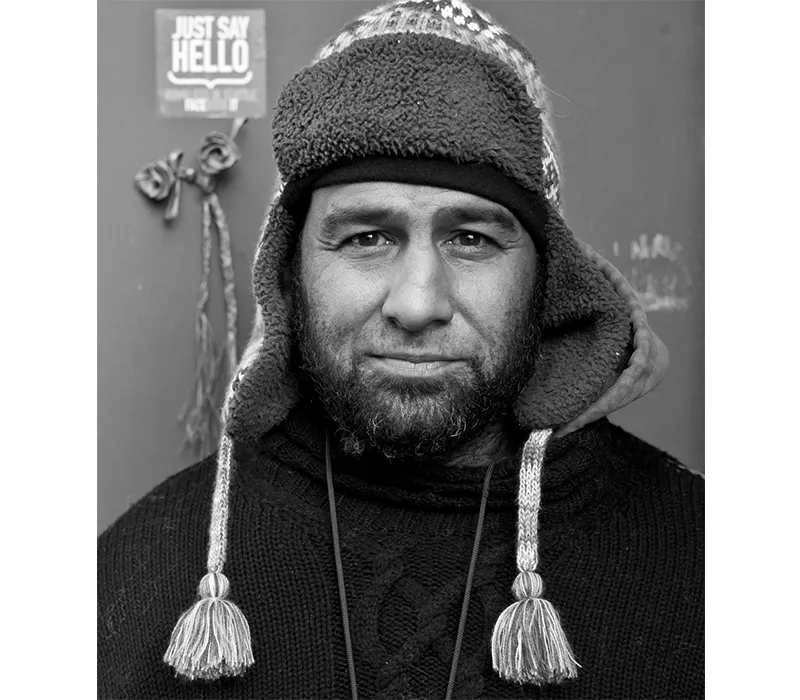

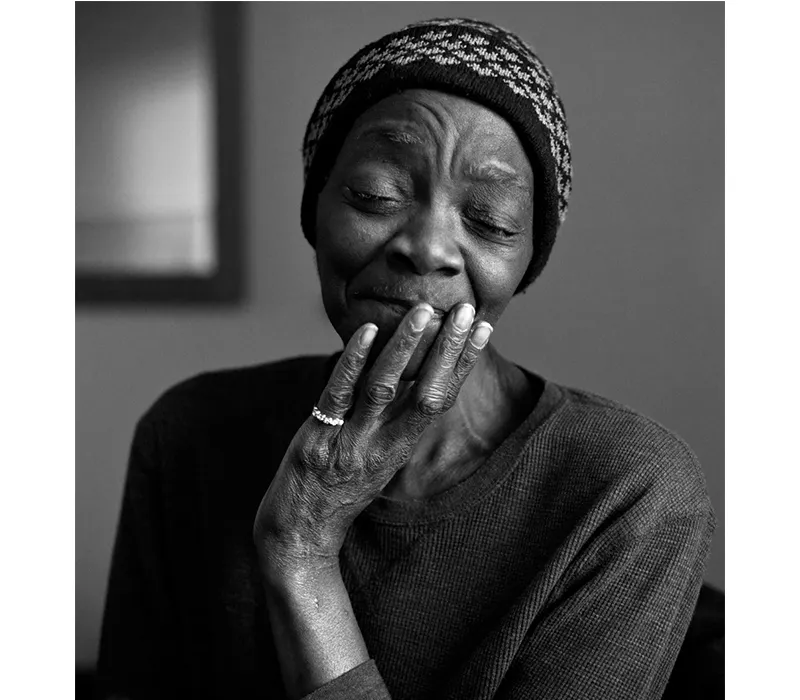

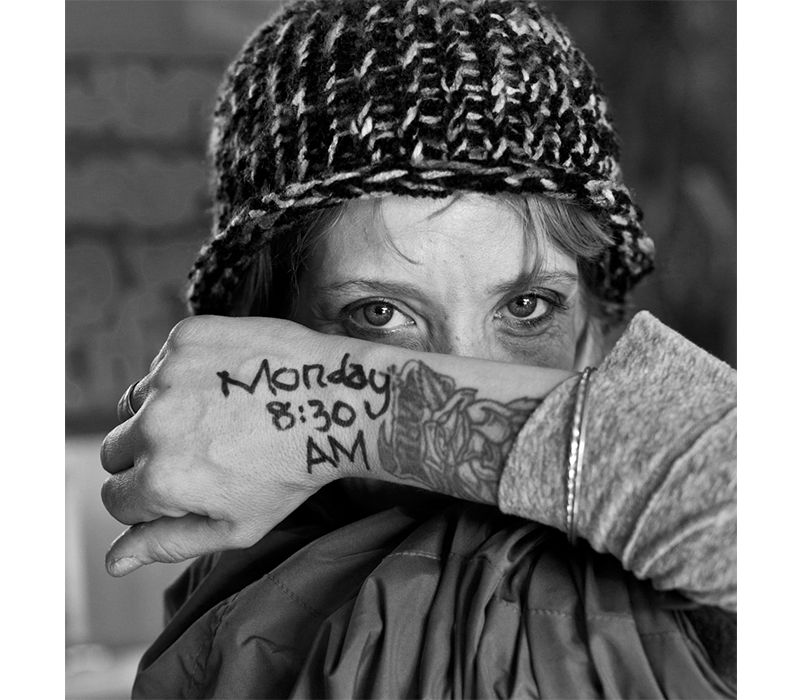

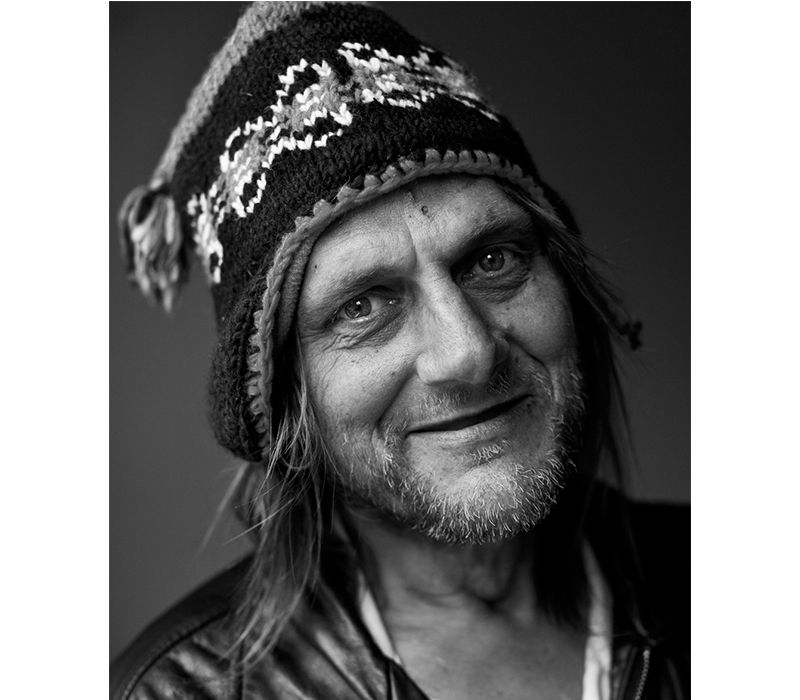

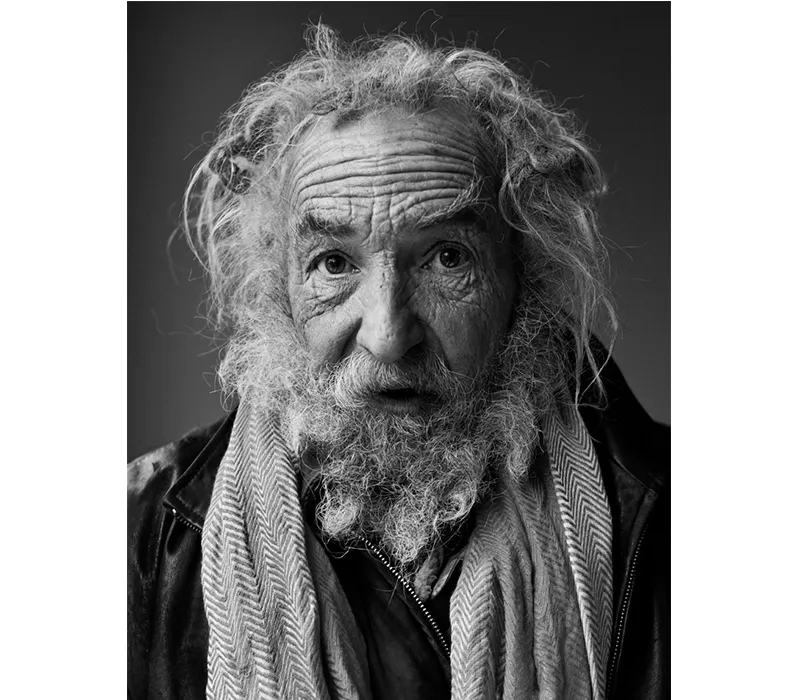

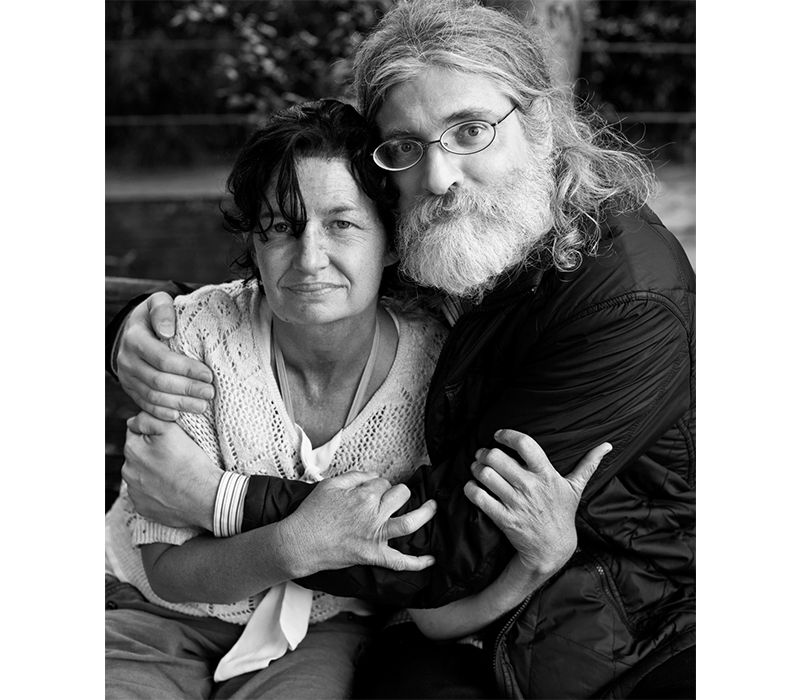

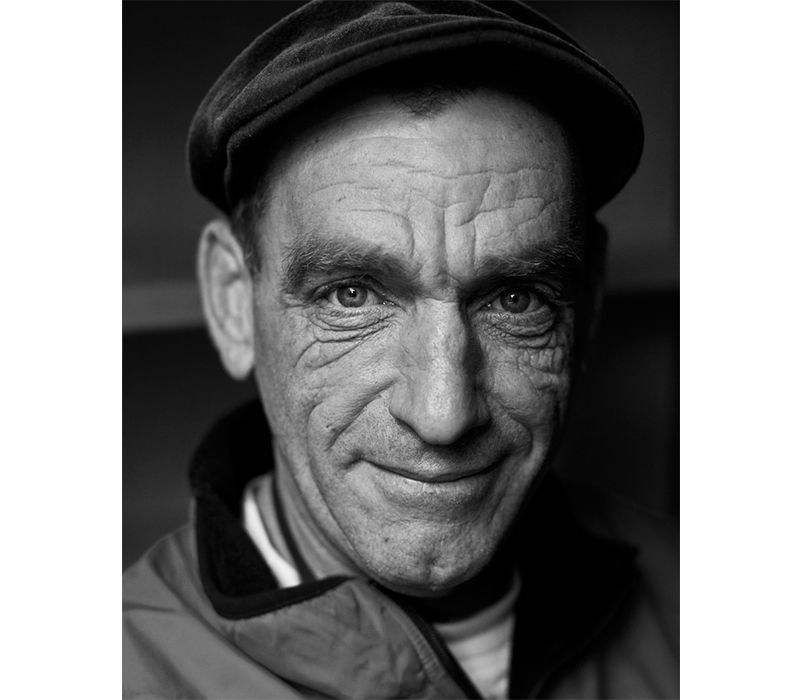

These Stirring Portraits Put a Face on Homelessness

Rex Hohlbein’s method of using social media to get tents, clothing, car repair and other needs to Seattle’s homeless is catching on in other cities

On a rainy August day, Rex Hohlbein approached a man sleeping in a shopping cart outside his architecture office and invited him in. “I said, ‘When you wake up, and if you want to, you can come in to that grey house and get a cup of tea,’” Hohlbein recalls.

The man, whose name is Chiaka, took him up on the offer, and as he dried out, he started showing Hohlbein the art he was working on—a children’s book and some large oil paintings. Impressed, Hohlbein told Chiaka he could store his art supplies in the shed out back and sleep there too. He even offered to set up a Facebook page, to help the artist spread the word about his work.

People in Seattle bought his paintings and started comissioning new ones. The next January, out of nowhere came a message from a teenager in Pittsburgh. She had searched his name in Google, the Facebook page had come up, and she was pretty sure Chiaka was her father. Hohlbein showed the post to Chiaka, who broke down. He’d left his family 10 years earlier because of depression and a host of other things. He told Hohlbein he had to get home.

Chiaka's family sent funds for his trip, and Hohlbein drove him to the airport. Driving home from the terminal, crying, Hohlbein was struck by the turn Chiaka’s life had taken.

“It occurred to me that I could do the same thing for other people,” he says. So, in 2011, Hohlbein started a Facebook page, Homeless in Seattle, where he’d post black-and-white portraits that he shoots himself of homeless people he met around town and short stories about them. He’d write about their back stories and add something about what they needed: a sleeping bag, socks or someone to help fix their car.

“Almost immediately people started reaching out,” he says. “Overnight my office turned into a drop-in center, and there was this crazy intermixing of people getting to know each other. There was this constant unsaid thought of, ‘You aren’t as scary as I thought.’”

Hohlbein often hears that people want to find a way to help, but they don’t have an inroad. Facebook, which has a low-barrier to entry and lets people engage on whatever level they’re comfortable with, proved to be a good, simple way to both humanize a group that’s often overlooked and to efficiently get them access to things they need. “Social media can be used in a powerful way,” he says. “People argue we’re not really relating any more, but in the busy life we tend to be leading we need simple ways to stay in touch.”

Nearly 17,000 people follow the Homeless in Seattle page, and they’re not just hitting the thumbs up button. “Over the five years, every single post has been answered,” Hohlbein says. “It’s this weird wishing well.”

The biggest barrier, and the one Hohlbein is now most focused on breaking down, is how deeply rooted the stereotypes about homeless people are, and how toxic they are to both the homeless and the housed. “No one chooses to be homeless,” he says. “There’s this misconception that either A: they’re choosing it, or B: they’ve made really poor choices. There’s this reap-what-you-sow, pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps mentality that’s really negative. But, almost without exception, this issue of homelessness is about trauma of some kind: mental health, abuse, PTSD or violence.”

Running Homeless in Seattle became so demanding that Hohlbein quit his job as an architect and started a non-profit, Facing Homelessness, in 2013 to support the effort. “I had two years of making below poverty [wages] after running a business that was really successful, but I couldn’t put it back in the box,” he says.

The community's response has been incredible and consistent. One woman bought and donated 29 sleeping bags. And as the effort grew, folks from other cities started reaching out. A guy named Mike Honmer, in Boulder, Colorado, saw Hohlbein's 2014 TED Talk, and asked if he could start a group there. Then Hohlbein started getting similar calls from Sacramento, San Francisco, Dallas and D.C., and as far away as Buenos Aires, Argentina. None of the subsequent groups are as big as the Seattle one yet, but he estimates there will be 100 similar efforts by the end of the year.

Hohlbein made a logo, incorporating the “Just say hello" slogan of Facing Homelessness, and sent it out to the other cities. The groups are all slightly different in their intent and execution, and they’ve each changed the logo slightly, but there’s a common thread of using portraits and social media to humanize homeless people and to try to encourage interaction. Hohlbein thinks black and white photos allow the viewer to focus on the subject's beauty, and for all the photos he's shot, not one subject has complained about how he or she looks—a rare reaction from sitters. He says that a lot of times even just a greeting or eye contact can be powerful to someone who is used to being ignored.

“Most people who are homeless feel invisible. Imagine just a week of everybody turning away from you and how crazy that would be for your self-esteem,” he says. “You can make a difference, with no promise of fixing that person, just by saying ‘I see you.’”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0196_2.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0196_2.JPG)