This Handheld Ultrasound Scanner Could Be the Next Stethoscope

Clarius co-founder and CEO Laurent Pelissier believes the affordable, wireless device could revolutionize health care

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/86/6a/866a0adf-025e-4d6b-bcb8-98bd49d7a4f6/clarius_video_screenshot.jpg)

When most people think about an ultrasound, a hulking machine that gives doctors and parents views of a developing fetus typically comes to mind. But engineers are putting the technology—useful at many points of care, from emergency to sports medicine—in the palm of our hands.

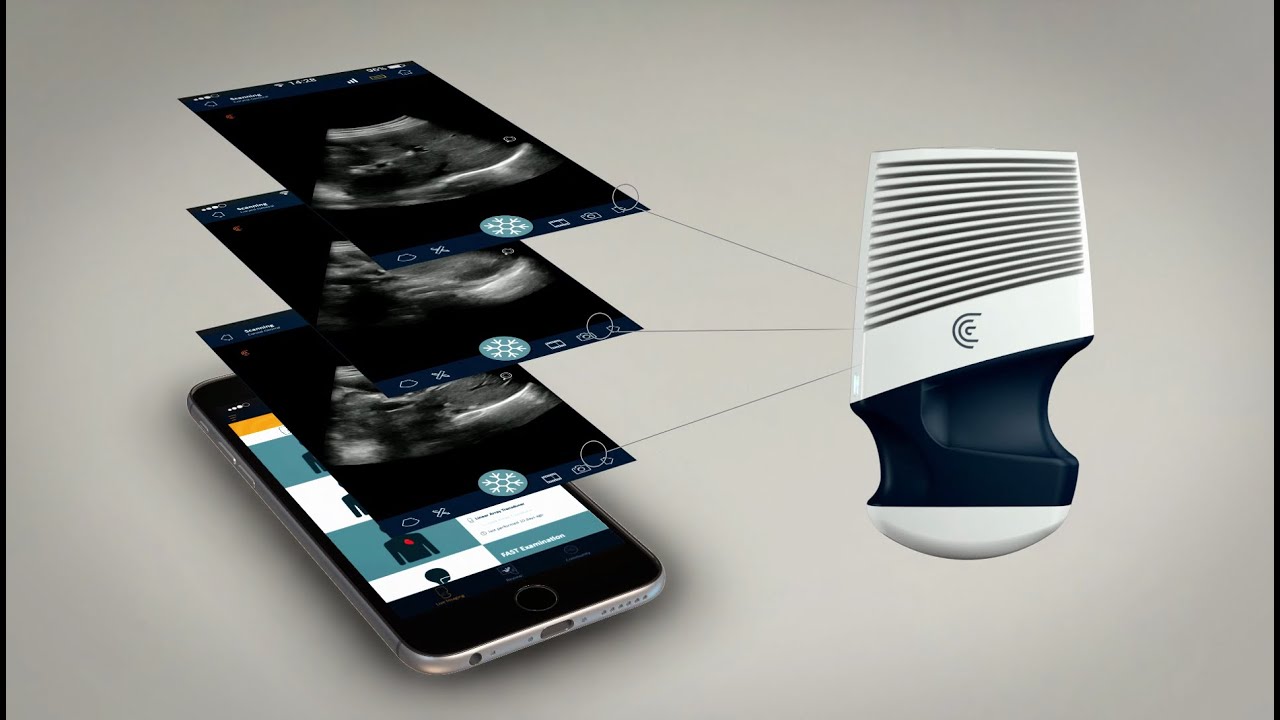

Since its founding in 2014, the Vancouver-based startup Clarius has specialized in developing a handheld ultrasound scanner that connects wirelessly to a smartphone app, available through iOS and Android app stores, to display the image. Medical professionals can move the Clarius scanner on the desired area, no gel required. Battery powered, water-submersible and drop resistant, the device offers high-quality imaging of the entire chest and abdomen, including vital organs such as the heart and lungs.

With a smaller, portable scanner able to provide the same image quality as a massive machine, the possibilities rapidly expand. For one, it means medical teams no longer have to rely on a single machine, when a department or institution can purchase many smaller scanners with lower price tags.

Clarius makes several handheld scanners ranging in price from $6,900 to $9,900, from the currently available cheaper black and white image C3 model to a full-color L7 premium scanner that should be available by summer 2017. Traditionally, the cost of an ultrasound system has started around $25,000 with high-end systems topping out over $250,000.

Increased access to ultrasound technology certainly has its benefits. Sonograms, the images produced by the high-frequency sound waves made by an ultrasound machine, offer better images of soft tissue injuries and diseases than x-rays. Ultrasounds are also better at distinguishing a solid mass from a fluid-filled growth as each produces a different echo.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the Clarius ultrasound scanner for use in December 2016, and Health Canada followed suit in January 2017. The company has applied for 14 patents to date relating to several aspects of the scanner, including its ability to generate high quality images (U.S. Pat. App. 2016/0151045 A1) and its wireless connectivity technology (U.S. Pat. App. 2016/0278739 A1). The scanners have been in use in teaching environments since June 2016.

Clarius co-founder and CEO Laurent Pelissier spoke with Smithsonian.com about the invention.

How did the idea for Clarius come about?

I’ve been in the ultrasound world for nearly 20 years. I started a company called Ultrasonix, and we created software for researchers recording ultrasounds. We were acquired in 2013, and after staying on for six months, I was ready to do something new.

I met my co-founder, Dave Willis, who was with SonoSite, another company in the ultrasound software space that was purchased by Fuji in 2013. He was also looking for his next opportunity. Everything we know is ultrasound, so we wondered, if this is all we know, what else can we do to improve this technology?

People think of ultrasounds and they think about pregnancy, but that only accounts for about 20 percent of the ultrasound market. Ultrasound technology is used in many instances, ranging from detecting gallstones to cancer.

Traditionally, big machines in hospitals are how we think of ultrasounds. In the past 10 years, the technology has been miniaturized, but still used for critical care situations, to find out what’s happening in a distressed body. Ultrasound technology found its way into emergency departments and the ICU, but there are other points of care applications. For example, before a surgery, it may be necessary to inject a regional anesthetic. Ultrasound can be used for inserting the needle precisely, with fewer attempts and less bruising.

Thinking about the miniaturization of the technology at a higher level, we now have ultrasound training programs in medical schools. More and more physicians are aware of the potential and trained on ultrasounds. We think that within five to 10 years, a vast amount of doctors, general practitioners or otherwise, will own their own ultrasound machines. This can enable physicians to see how a heart functions instead of just guessing, and we believe this could be the next stethoscope.

What’s your elevator pitch?

We’re trying to put ultrasound technology into the hands of every physician out there. We want to become the leading imaging company for general medicine by providing visual tools that help a variety of physicians at various points of care.

What are some of the applications? Where is this most useful, and are there use cases that surprised you?

The first applications are obvious opportunities within the existing point-of-care market. It’s just that our small scanner is easier to use and is more affordable, while it delivers the same level of performance. Existing users in this market include emergency department physicians, anyone administering regional anesthesia, and professionals in sports medicine who need a better look at muscle function. We’ve also had interest from obstetricians.

A new market opening with major potential that isn’t completely surprising is for EMS—bringing ultrasound even closer to the point of accident, and being able to use the technology before you get to an emergency room. A paramedic can look and evaluate internal damage, and that can have a significant effect on whether a patient goes straight to the hospital, or whether some triage can happen at the accident site and the patient’s information is sent ahead.

Another opportunity we see is in home care—specifically with an aging population. Nurses and home health workers can use ultrasound as part of their general routine to monitor vitals such as heart function. In home care, ultrasound can also be useful if blood samples are needed. Ultrasound can help see the point of access and reduce the need for multiple attempts to draw blood.

Is your device relatively novel?

There are various companies doing this sort of thing, which is good because it shows there is a market. It is possible to read an EKG on a phone now, too. There’s a need for all of this, but the technological advancement takes time. We’re the first ultrasound developer to go wireless and pair our device with a smartphone.

Were there any unexpected hurdles along the way?

We anticipated a lot of new product testing, as with any new technology, and we had to do a bit of homework on that front. Generally, because of our combined previous experience, we had a plan to get to here. We’re growing quickly, and while our initial focus was on R&D and product generation, now we’re finding talent and assembling a marketing team.

Vancouver is hub for ultrasound technology, between the University of British Columbia and our previous companies based here. We are fortunate in that regard.

What’s next? How do you sell this sort of device?

The past two years we were focused on R&D and could rely on outside investment. Now that we have regulatory clearance, we’re entering the commercial phase. We also have a big partnership announcement coming in March.

In the immediate future, we’re selling our scanner through direct sales. Usually, ultrasound equipment is sold with a large number of reps traveling to a hospital with a large machine. There are a lot of cold calls. By contrast, most of our selling process will be done remotely. We’re focusing on online sales and regional trade shows, as well as opportunities for further use in educational environments.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/brittany_headshot_crop.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/brittany_headshot_crop.jpg)