This Interactive Installation Rains a Poem Down on Viewers

Artists Camille Utterback and Romy Achituv wrote the software that drives an artwork, in which onlookers catch letters falling on a large screen

When people hear the word “art,” they may think of it in the traditional sense: hanging on a wall to be observed only. But artist Camille Utterback seeks to create pieces that physically engage viewers.

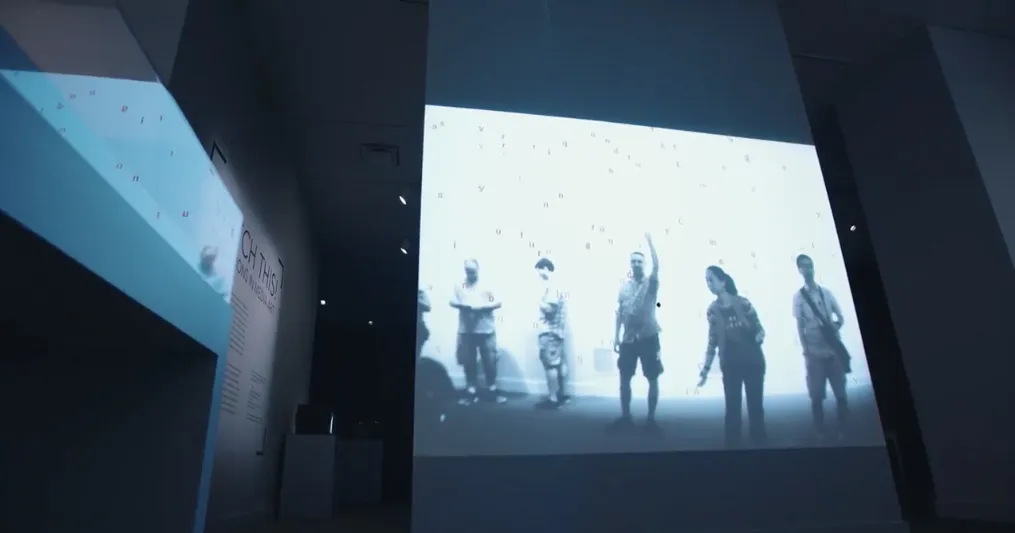

The Stanford University art professor blends her art with computer technology in ways that encourage people to interact with it. This is particularly evident in Text Rain, an interactive digital installation that she created in 1999 with Romy Achituv, then a classmate in New York University’s interactive telecommunications program.

Viewers stand in front of a large screen, where their images are projected and letters trickle down like rain. Catch a falling phrase, lift it up—the viewer can manipulate the text. At first glance, it looks like alphabet soup, but the letters are not random. They are excerpted from “Talk, You,” a poem by Evan Zimroth that captures the complexity of conversation. The artists thought the poem—and its message that conversation is physical, emotional and intellectual—fit the dynamic experience they were trying to create.

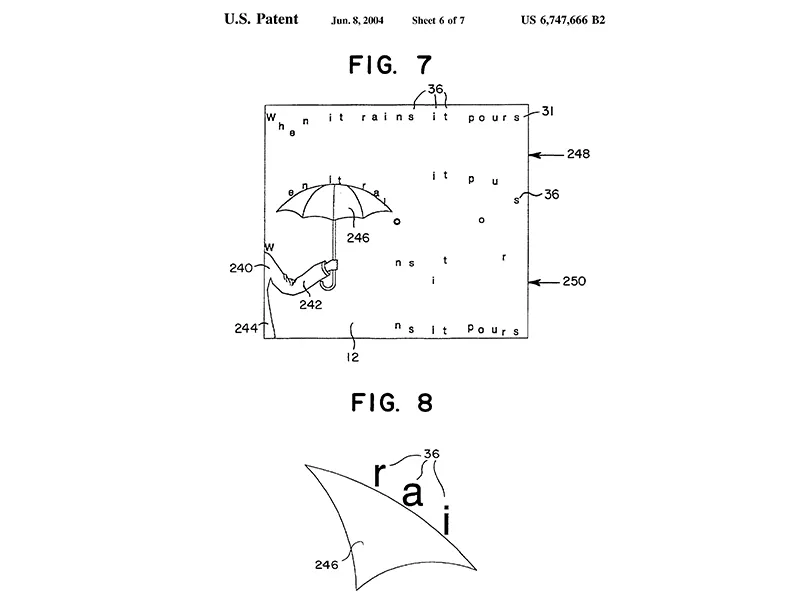

The Smithsonian American Art Museum recently acquired Text Rain. Michael Mansfield, the museum’s curator of film and media arts, says the “critically important” installation “really set the stage for how we engage in a museum space.” Utterback and Achituv received a patent in 2004 for the video tracking software that drives the piece.

How do computers and technology play a role in your work?

There is the hardware. A camera or a touch sensor can collect information about what people are doing in a physical space. There's the software component, which is what I write that creates the rules about how the system responds to that input. It's usually visual, because I'm a visual artist—so something is happening in a projector or on a monitor or with LED lights based on that input. And then there is obviously what people do in this space. It's really a feedback loop. Generally, nothing will happen in the system unless people are doing something.

How does this type of interactive installation work?

It has some computational aspects, so it's running on a computer or a microcontroller, or just some piece of technology that processes a set of instructions. I write the instructions, so everything that is happening on the screens is following my instructions. The instructions are to draw a line if the person is walking in a certain way or make a letter stop if someone has a hand outstretched. For me, it's a really exciting way to make art, because I'm creating the situation, but it is always open to what people are doing.

Why do you think Text Rain still feels so relevant today?

It's been amazing to watch the life of a piece that is from 1999—now it's 2015 and to still see people be so taken with it. In some ways, our experience has caught up with the technology that Romy and I used in the earlier version. People didn’t even know what a projector was when we were first showing it, that was very unusual for people to see. But the fact that it is so compelling I think has to do with some of the aesthetic decisions that we made.

What does it mean for art to be innovative?

I think art is innovative, because it's drawing connections that aren't being drawn. There are a lot of ways you could talk about that, but for me it's about addressing some of the things that aren't happening in our barter consumer culture. What's exciting about being an artist is solving different problems than the problem that would make a good business or a good product. Maybe eventually those things get incorporated in different ways into our culture.

Tell us about your patent.

Romy and I were asking, why don’t computer systems engage our bodies? It is just your fingers typing, or even when you think now of how much energy we put into our little phones when we have our whole amazing range of movement that isn’t very well addressed by these systems.

Because we weren't super sophisticated programmers, we came up with a really simple way to solve that problem. I think the reason that the patent filled is that it was actually a simpler computer vision system than some of the other systems that had been patented before it.

What do you hope people take from this piece?

I hope that when someone engages with one of my interactive installations he or she starts making hypotheses about what the system is reacting to and why. What I really hope is that then people extend that out and think about how all of our actions impact the world around us. We are part of so many systems—the environment, our families, our communities—and everything that we do is embedded in all these other processes. We are very powerful, but we are also part of these other rule sets.