This New App Promises to Sharpen Your Eyesight

Forget Lasik. A neuroscientist from the University of California Riverside swears that his exercises can improve your vision

:focal(185x443:186x444)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/f8/e6f859a4-ad50-48fe-96dd-579211c36c56/eye-test.jpg)

When it comes to worsening eyesight, we are quick to think of three remedies: eyeglasses, contact lenses and Lasik. But, could a video game a day, actually keep the eye doctor away?

Aaron Seitz thinks so. The neuroscientist from the University of California, Riverside argues that training the brain to better adapt to changing eyes is no different than exercising the body to be stronger or faster.

“One aspect of vision is the optics of your eyes, and if you want your vision to be best, you want to make optics the best possible—through Lasik, glasses or surgery,” says Seitz. But our sense of sight also depends on our brain's ability to process visual information. “We like to think that our brain is going to be doing this optimally," he adds, "but that’s not the case."

UltimEyes, the app Seitz released last month, tests for neuroplasticity, or how well the brain's pathways change with our bodies and their surroundings over time. The user completes visual exercises specifically designed to assess how well his or her brain’s visual system is able to react to certain cues.

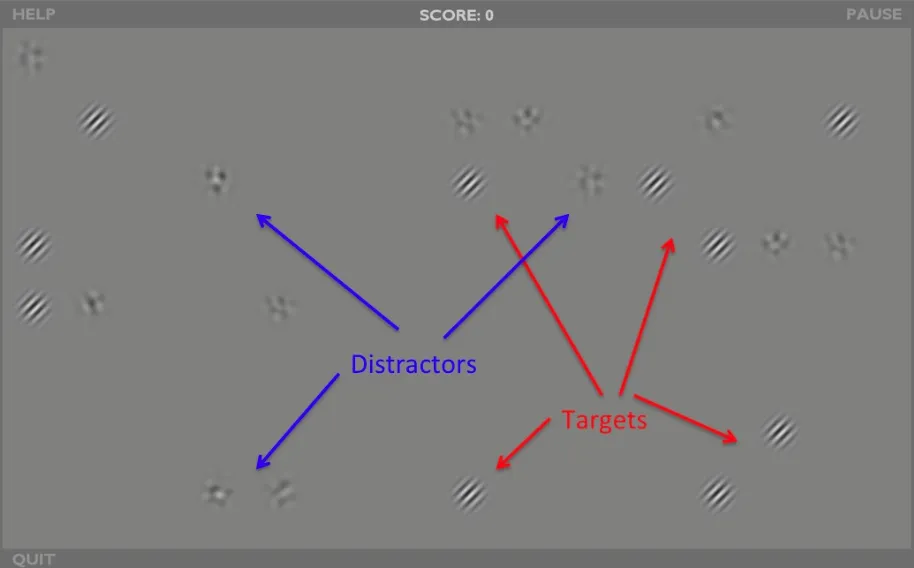

The app shows users “targets” and “distractors”—fuzzy bumps of varying depths and textures strewn across a flat gray screen—and then asks them to click the targets to earn points. If distractors are hit instead, users lose points.

Each “level” has different targets. Some of the targets have ridges, like potato chips, and how close the ridges are together varies; the tighter they are, the harder it is to tell if there are ridges at all. This tests visual acuity. Others have low contrast, making them blend in with the background on the screen.

“[They are] the kinds of stimuli that will excite cells in the visual cortex, so with repeated practice, you’re able to identify these when they are harder and harder to see, and, in that sense, you’re able to exercise those visual cells,” Seitz says.

The results, so far, have been promising. The university’s baseball team, the first group to test the app, saw a 31 percent improvement in their vision (gaining about two lines on a vision chart) after using the app four times a week for two months at 25 minutes a time, according to results published in the journal Current Biology.

The 19 players who trained with the app also saw varying improvements in their peripheral vision and their ability to see things in low light; some improved their vision to 20/7.5, which means they could see at 20 feet what most people can only see from 7.5, or about a third of that distance.

“It’s one thing to have a prototype that will run on a computer in a lab; it’s another thing to get it so it’s robust enough so people in the world can use it,” Seitz says. “I wanted to see how we can establish that this actually has an impact on things that people actually do.”

Even those of us who aren’t athletes can benefit from the program, Seitz says. Our eyes are constantly changing throughout our lives—and while, “early on in life the visual system is very plastic, pretty much past the age of 25, every aspect of cognition starts to get a bit worse,” he explains.

"As we get older, our eyes are constantly changing, but our brain doesn’t catch up with these changes,” Seitz says. “The program is designed to exercise your brain to accomplish two things: to try to re-optimize to the eyes that you have at that point and to exercise the system so it’s more efficient in general.”

But it’s healthy to have some skepticism, Seitz says. His tests, which have since included the university's softball team, raised more questions than they answered.

For instance, some players saw greater improvements in one eye, or with a certain skill, over another. And, while Seitz estimates up to two years, it is not immediately clear how long the effects last and also what kind of maintenance is required, or which exercises help certain conditions versus others.

Since his early studies were not funded, the neuroscientist relied on volunteers. He wasn’t able to set placebo conditions or reach out to other groups with a lower baseline vision. Though 20/20 is the goal for most of us, it puts you at the back of the pack in baseball, where players tend to have above-average vision in the first place.

Seitz now has funding to focus on specific groups—for instance, those who have age-related macular degeneration, various mental illnesses or have had cataract surgery. He’s also working with the Los Angeles Police Department, and soon, visually-impaired students at a school for the blind, which will give him a better handle on how the games affect the vision of different populations, he says.

Since its launch, the app has reached about 20,000 downloads. As demand grows, Seitz hopes to build “opt-in” permissions that would allow users to share the results of vision tests before and after the program, along with other data like age and sex. He also wants to enable video uploads, so he can track users’ eye movements as they complete each exercise.

“We have the possibility of getting 50,000, 100,000 people on a study, if you can get enough people to have the app in their hand,” he says. “When you’re building in better assessment, better data on who gets benefits and who doesn’t and a way to predict that, it’s much better science as well.”

Seitz is also excited about what something like his app could mean for the broader worlds of medicine and research.

“From a medical perspective," he says, "what we’re seeing is that a lot of approaches that traditionally would only be available in a research lab are accessible in an outpatient basis.” In other words, thousands could be getting treatment without having to check into the hospital.

Seitz can’t promise, after some training with UltimEyes, that you’ll be able to ditch your glasses when you drive—and, in fact, recommends that you don’t. But, the app might be a more beneficial diversion than Angry Birds.

“We all know this idea of use it or lose it, and with any other skill that we engage in, we get rusty if we’re not actively practicing," he says. "Vision is really the same thing.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)