Tiny “Neural Dust” Sensors Could One Day Control Prostheses or Treat Disease

These devices could last inside the human body indefinitely, monitoring and controlling nerve and muscle impulses

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b0/0c/b00c534b-0e5d-4db6-934f-331fae97c8be/neural-dust-uc-berkeley.jpg)

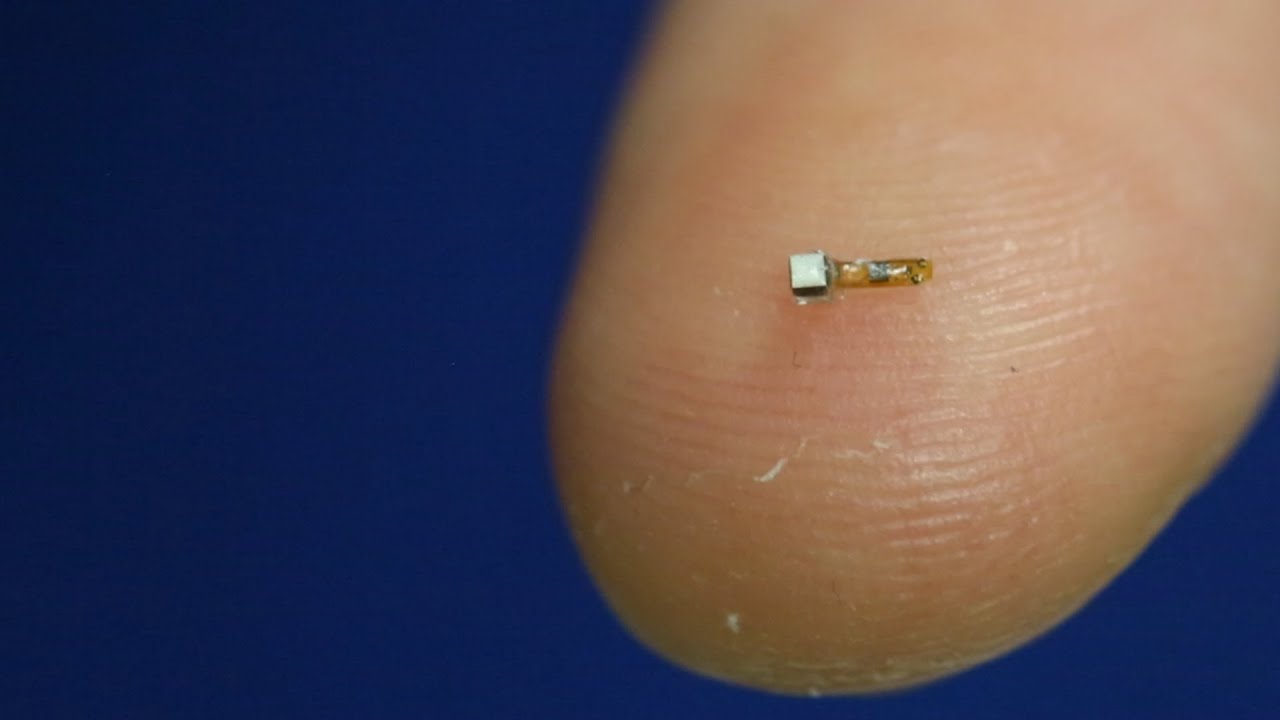

They’re tiny, wireless, battery-less sensors no larger than a piece of sand. But in the future, these “neural dust” sensors could be used to power prosthetics, monitor organ health and track the progression of tumors.

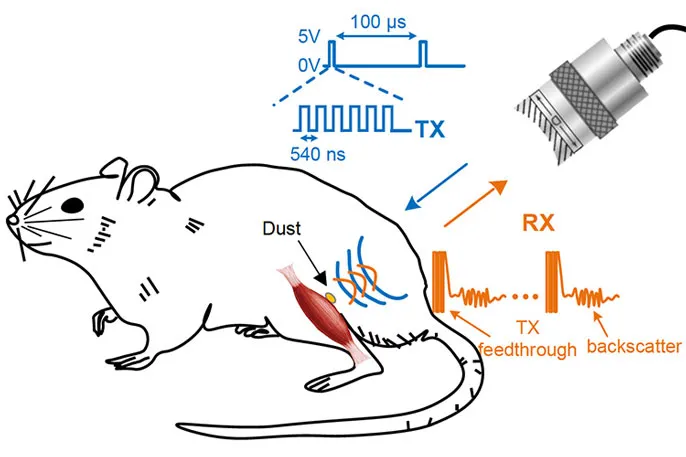

A team of engineers and neuroscientists at the University of California, Berkeley have been working on the technology for half a decade. They’ve now managed to implant the sensors inside rats, where they monitor nerve and muscle impulses via ultrasound. Their research appears in the journal Neuron.

“There’s a lot of exciting things that this opens the door to,” says Michel Maharbiz, a professor of engineering and one of the study’s two main authors.

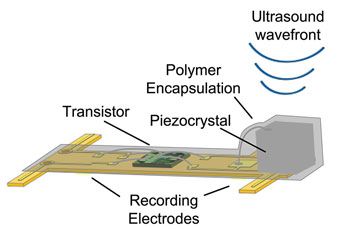

The neural dust sensors developed by Maharbiz and his co-author, neuroscientist Jose Carmena, consist of a piezoelectric crystal (that produces a voltage in response to physical pressure) connected to a simple electronic circuit, all mounted on a tiny polymer board. A change in the nerve or muscle fiber surrounding the sensor changes the vibrations of the crystal. These fluctuations, which can be captured by ultrasound, give researchers a sense of what might be going on deep within the body.

Building interfaces to record or stimulate the nervous system that will also last inside the body for decades has been a long-standing puzzle, Maharbiz says. Many implants degrade after a year or two. Some require wires that protrude from the skin. Others simply don’t work efficiently. Historically, scientists have used radio frequency to communicate with medical implants. This is fine for larger implants, says Maharbiz. But for tiny implants like the neural dust, radio waves are too large to work efficiently. So the team instead tried ultrasound, which turns out to work much better.

Moving forward, the team is experimenting with building neural dust sensors out of a variety of different materials safe for use in the human body. They’re also trying to make the sensors much smaller, small enough to actually fit inside nerves. So far, the sensors have been used in the peripheral nervous system and in muscles, but, if shrunken, they could potentially be implanted directly into the central nervous system or the brain.

Minor surgery was needed to get the sensors inside the rats. The team is currently working with microsurgeons to see what kinds of laparoscopic or endoscopic technologies might be best for implanting the devices in a minimally invasive way.

It may be years before the technology is ready for human testing, Maharbiz says. But down the road, the neural dust has potential to be used to power prosthetics via nerve impulses. A paralyzed person could theoretically control a computer or an amputee could power a robot hand using the sensors. The neural dust could also be used to track health data, such as oxygen levels, pH or the presence of certain chemical compounds, or to monitor organ function. In cancer patients, sensors implanted near tumors could monitor their growth on an ongoing basis.

“It’s a new frontier,” Maharbiz says. “There’s just an amazing amount you can do.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)