To Develop Tomorrow’s Engineers, Start Before They Can Tie Their Shoes

The Ramps and Pathways program encourages students to think like engineers before they’ve reached double digits

![]()

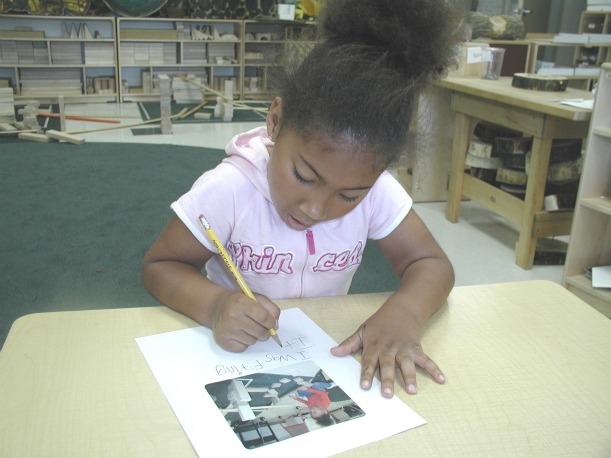

A first-grader in Waterloo, Iowa writes about the steps she took to build her Ramps and Pathways project, a task that transforms her into an engineer. Photo by Beth Van Meeteren

Think “student engineers,” and you probably have visions of high school or college students. But peek into in a small but growing number of classrooms around the country, and you’ll see engineering being taught in preschool and elementary school using a method called Ramps and Pathways.

In Ramps and Pathways classrooms, children explore the properties and possibilities inherent in a few simple materials: blocks, marbles, and strips of wooden cove molding, a long, thin construction material used to finish cabinets and trim ceilings. Teachers push desks and chairs out of the way to allow room for the sometimes-sprawling roller coasters that emerge. By building and adjusting inclines propped by blocks, children experiment with marbles moving along various paths. Their job is to test and retest different angles, figuring out new ways to take their marbles on a wild ride.

“We always see little sparks” of insights among the students, says Rosemary Geiken, an education professor at East Tennessee State University who assists elementary school teachers who have never used this teaching method before. One time, she says, she watched a little girl with three boys having trouble getting a marble to land in a bucket. The girl whispered to the boys. Soon they were all propping up the ramp differently and the marble dropped right in. “Now you know I’m a scientist,” the girl said to Geiken.

Ramps and Pathways started in Waterloo, Iowa in the late 1990s. Teachers for the Freeburg Early Childhood Program at the University of Northern Iowa, a lab school for preschool to second grade, wanted to see what kind of investigations children might pursue on their own. They provided kids with one-, two-, three- and four-foot lengths of cove molding and unit blocks.

Beth van Meeteren, then a first-grade teacher at Freeburg, captured video of these moments by placing cameras in the classrooms and starting documenting how they learned. She was struck by how the project held the students’ attention and led them to push themselves to create more challenging structures.

Once, for example, van Meeteren saw a first-grade student build a structure over the course of several days consisting of 13 three-foot ramps in a labyrinth-like ramp that spiraled down to the floor. The marble traveled 39 feet on a structure that took up only nine square feet of floor space. This was entirely the child’s idea, she says.

A pair of first-graders from Iowa work together to build a zig-zagging series of pathways that will carry a marble from top to bottom. Photo by Beth Van Meeteren

Today, Ramps and Pathways is used in elementary school classrooms in 18 schools throughout four counties of Tennessee where teachers are receiving coaching on how to use the program to teach engineering and science. The program is paid for with money from a Race to the Top grant from the U.S. Department of Education.

Other elementary school sites are in Iowa, Maryland and Virginia, in both in-class instruction and after-school clubs.

But Van Meeteren, who is now a professor at the University of Northern Iowa and wrote her dissertation on the subject, says the method is mostly taking root in preschool classrooms where teaching is more multidisciplinary and where children are not expected to always be sitting in seats.

At the elementary school level, hands-on science and engineering bumps up against the desire among educators and policymakers to ensure that children reach third-grade with proficient reading skills. Principals want to see evidence of children learning letters and numbers.

To help the program expand into the elementary grades, van Meeteren, Geiken and other science educators are intent on showing that these activities can, in fact, promote math and reading too. Watch videos of these projects and signs emerge of children learning counting and sorting skills as they grapple with how to adapt their constructions. Van Meeteren says she has been encouraging teachers to integrate science into reading by asking children to write about their contraptions and the problems they solved to make them work. She and Betty Zan, director of the Regents’ Center for Early Developmental Education at the University of Northern Iowa, are seeking an Investing in Innovation grant from the U.S. Department of Education to show how science lessons, such as the approaches used in Ramps and Pathways, could be integrated into the 90-minute reading time periods prevalent in elementary schools.

The projects spur children to think like engineers, discovering connections between actions and reactions and adjusting their plans accordingly.

One child, for example, was so intent on making his ramp work that he spent more than seven minutes quietly contemplating options and making adjustments, until he finally got the marble to roll through four different ramps at four different angles.

“I’d love to get this into more classrooms,” van Meeteren says. “It seems that only gifted classrooms are allowed this quality instruction. All children benefit.”

Video Bonus: To see video clips of children working on Ramps and Pathways projects, scroll down to the middle pages of this article from the journal of Early Childhood Research and Practice.

Lisa Guernsey is the director of the Early Education Initiative at the New America Foundation and the author of Screen Time: How Electronic Media — From Baby Videos to Educational Software — Affects Your Young Child.