Traveling to Japan—Through a Symphony of Smells

A new performance, staged in Los Angeles this weekend, revives one man’s failed attempt to put on a smell and sound production more than a century ago

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/d6/6bd60e21-2576-414c-913c-7bcf38f3742d/_triptojapan_rehearsal_120213_bennettbarbakow2.jpg)

So much of travel is visual. That first instinct, when stepping off a plane or a subway car, is to take in what you see.

But can you remember what you smell?

Producer and curator Saskia Wilson-Brown and a 13-artist team have convinced at least a few hundred people to make the jaunt from Los Angeles to Japan through only a handful of scents in “Japan in Sixteen Minutes, Revisited,” a show that recreates a trip to Tokyo—from an airport shuttle to the first moments of sleep in a hotel room across the Pacific—with perfumes and an ambient soundtrack.

The audience won’t travel outside L.A.’s Hammer Museum, where the show is being staged this weekend; instead of making the 12-hour journey, visitors will sit, blindfolded, in rows of stationary seats, using their noses as a compass.

“[Smell] is the one sense that hasn’t really been explored to its total potential yet,” says Wilson-Brown, who founded the L.A.-based Institute for Art and Olfaction in 2012 to give the art and science of perfumery “a larger platform” than shelves in department stores.

Scent is an art form, she says, that can be as powerful as sound or imagery.

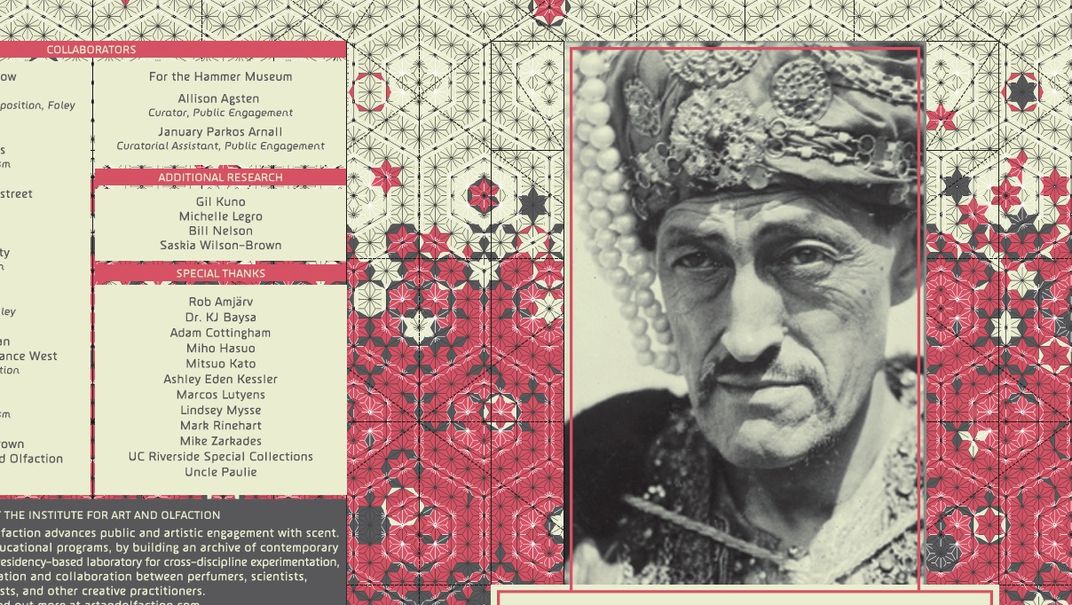

As far as we can tell, Wilson-Brown and her team are among the few to attempt a show guided primarily by scent, though they found their inspiration from a show more than a century ago. In 1902, a New York artist and “grand eccentric” named Sadakichi Hartmann pioneered the concept—with a production that set the audience off from the New York Harbor—and made plans to bring what would be the first recorded public scent concert to life.

But his attempt, “A Trip to Japan in Sixteen Minutes,” was a “total failure,” Wilson-Brown says. Hartmann planned the show for years only to have his venue, the Carnegie Lyceum, fall through. Instead, he crammed his cast into a Burlesque house in New York City that usually featured comedy; as he began to fan scents into the crowd, costumed geishas at his side, he was booed off stage.

As far as Wilson-Brown could tell, he never attempted a public performance again.

The story spoke to her while she was chatting with a bookshop owner more than a year ago, but taking on the feat herself didn’t seem realistic—that is, until she stumbled across some collaborators with whom Hartmann’s story also resonated.

“I think people really respond to somebody’s failure and trying to make it right for him,” she says.

And so a mission began to keep Hartmann’s original intentions at heart, but create a show with a bit more focus and, a century later, more modern effects.

First up: strip the audience of sight. Hartmann’s venture featured not only geishas, but also a number of musical and theatrical acts to accompany his scents. Wilson-Brown’s team, however, “really wanted to focus on the olfactory and auditory journey,” and decided to blindfold the audience, though a few visual cues in the program put the performance in context.

The choice allowed the group to truly build a performance with smell at its core, a challenge because scent is so subjective. What Brown smells when she steps on a subway, for instance, could be completely different than the aromas sensed by the passenger beside her.

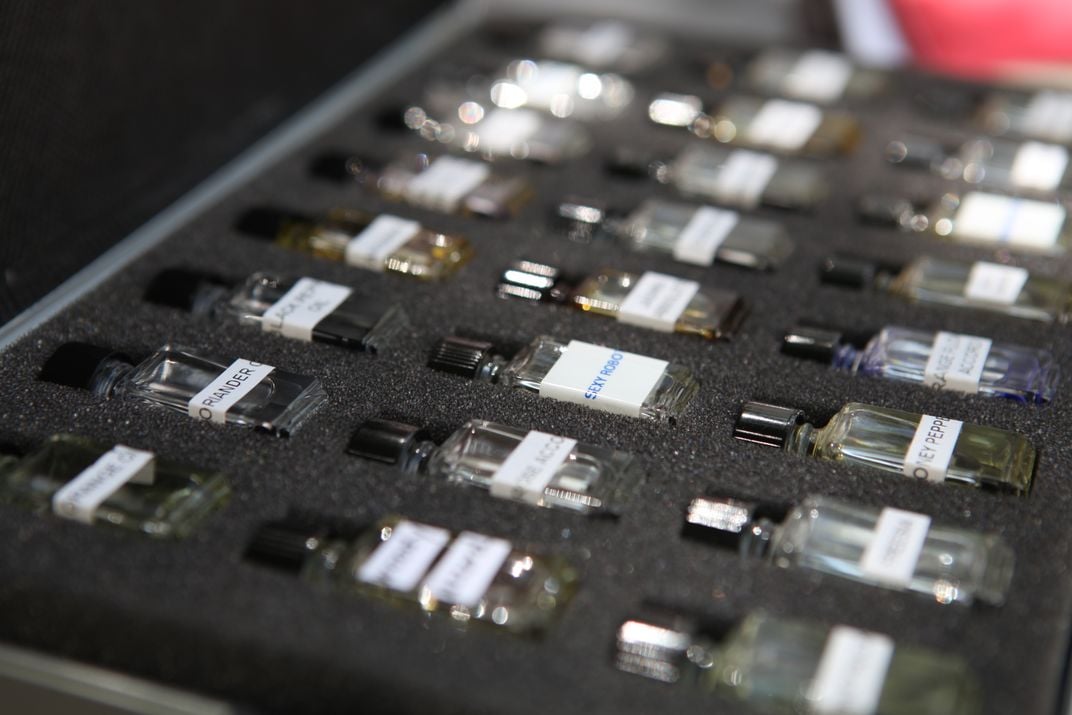

Rather than use single scents as Hartmann did in his performance, perfume artist Sherri Sebastian went after more complex aromas, in part to capture the range of smells that identify certain places. The show’s final “scent compositions” are just that: perfumes that use up to two and a half dozen ingredients to recreate places—an airport terminal, city streets, a hotel bed—along the journey.

Those smells won’t be as literal as the audience might think. While waiting for a shuttle in L.A., the audience might get a hint of a passing ice cream truck in a perfume with a “creamy lactonic base, sweet candy overtones and a healthy dose of green notes inspired by the vegetation and palm trees in Los Angeles,” Wilson-Brown says. The arrival in Tokyo will overwhelm the room not with gasoline, but with a note of rhubarb. The way the rhubarb's tartness hits the nose sort of mimics the intensity of bright city lights.

Adding to the challenge of mixing the show’s six perfumes was figuring out how to float them over the audience—and then retract them to make way for a next scent. In Hartmann’s show, which featured a few dozen scents, he used a hand fan to float each perfume into the crowd, which as one might imagine, was not only time-intensive but also not very effective. For Wilson-Brown’s show, the artists behind Beski Projekts, an exhibition design firm, built a $3,000 “smell propagation machine,” a monstrous contraption made with steel poles, plastic tubing and pumps, among other gadgets. The perfumes are loaded into the machine in vials and dispersed automatically at specific intervals throughout the show.

"A multi-scensory affair seals the deal in my experience; that’s what people respond to,” Wilson-Brown says, which is why she enlisted the help of composers Bennett Barbakow and Julia Owen to create a soundtrack to accompany the journey.

At first, Barbakow says, they researched stock audio clips and collected what ambient sounds they could. But in the end, the pair recorded each of the soundtrack’s thousand clips themselves, from passing cars to noises on the subway.

The soundtrack, pumped through eight speakers placed around the makeshift auditorium, will help transition the audience from place to place. The creators will also keep some aspects of live performance from the original show. Barbakow is planning 50 live sound elements to make the experience more realistic. As the audience arrives at the airport, a suitcase will be wheeled across the front stage; after take-off, a drink cart will shoot down the center aisle, while ice cubes clink in scattered bourbon glasses.

Barbakow says he tried to create a balance between sounds and scents through a loose musical composition that’s “all about dynamics.” Some moments—subway rides, navigating the city—will be intense, while in others, the audience will “feel intimately there with just a few layers of sound.”

The show is sold out in Los Angeles, but Wilson-Brown hopes to bring it to other cities across the U.S. and the world.

“I love the process of what you can do with perfume and scent in general,” she says, “It’s taking a commercial entity and turning it into something subversive, and tweaking people’s expectations. It makes you reflect.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)