This Ultrasound Patch Monitors Blood Pressure in Deep Arteries

The flexible wearable could be an alternative to current invasive methods of measuring central blood pressure within the human body

:focal(548x268:549x269)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a5/17/a517e030-4020-40af-9604-7d48ce34dc0e/cover-image-ultrasound-patch-on-finger.jpg)

If you want to monitor the blood pressure in someone’s arm, just slap on a blood pressure cuff. But if you want to measure blood pressure inside someone’s heart or lungs, that’s much more complicated. It involves catheterization—threading a tiny probe through a blood vessel in the arm, groin or neck all the way to the organ. It must be done in a hospital with sedation, and has potential for a number of risks, including heart attack, stroke, infection and bleeding.

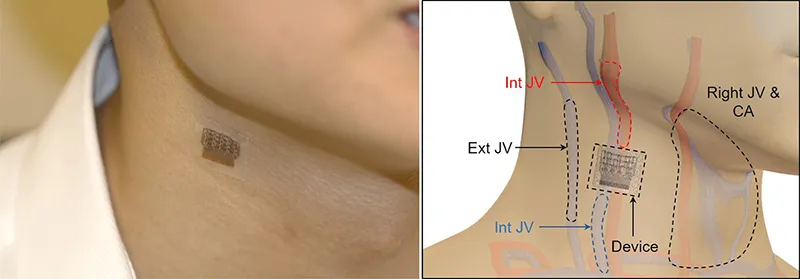

Now, a team of researchers from the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) has developed a wearable ultrasound patch they say can non-invasively monitor blood pressure in arteries far beneath the skin. The patch could monitor patients with heart or lung diseases or other problems in real-time without any risky procedures. It could also potentially help detect cardiovascular problems earlier than traditional monitoring methods.

“What you measure [with a cuff] is the peripheral blood pressure—your arm, your wrist, your foot,” says Sheng Xu, a professor of nanoengineering at the University of California, San Diego's Jacobs School of Engineering who led the study published last month in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering. “Those measures are meaningful, but they are less meaningful than the measures inside your key organs like your heart, your lungs, your brain, your kidneys.”

Blood pressure cuffs only give two discrete numbers, the systolic and diastolic, Xu explains. The ultrasound patch gives information in the form of a continuous wave, measuring some 5,000 blood pressure values per second. This gives doctors far more potentially useful data than just systolic and diastolic readings, as each value represents a specific activity of the heart.

“Each peak, each notch in this wave form actually contains abundant information about your health status,” he says.

The patch could be useful for monitoring a large range of diseases, Xu says, including heart valve abnormalities, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary embolism, blood vessel abnormalities and shock. It could also monitor patients who are critically ill or undergoing surgery.

The patch was tested on one subject’s forearm, wrist, neck and foot, both while the subject was exercising and at rest. The patch itself consists of a thin elastomer sheet with small “islands” of electrodes and piezoelectric transducers that create ultrasound waves from electricity. The whole structure can bend to conform with moving human skin without changing its accuracy.

There is currently a non-invasive method of monitoring central blood pressure, using a pen-like device called a tonometer directly above a major blood vessel. But accurate tonometer readings require precise pressure and angle, and measurements can vary widely depending on the technician, making them notoriously inaccurate. In the study, the ultrasound patch was much more accurate than a tonometer reading.

“It certainly looks very promising,” says Chwee Teck Lim, a professor of biomedical engineering at the National University of Singapore, who studies medical wearables.

The fact that the patch is soft and comfortable is important, he says, and it’s portable, meaning it could be used out of the hospital or in resource-poor settings.

“Such a patch can yield important information not only about blood pressure, but even possibly about certain cardiovascular diseases not normally detectable by the current blood pressure monitor,” says Lim, explaining that the patch could potentially detect the blood vessel stiffness associated with atherosclerosis.

The team hopes to test their patch against the current gold standard, catheterization. They are also looking to find industry collaborators who want to make the technology into a usable product. That will involve a number of further steps. Right now the team has demonstrated the sensor itself, but the prototype is connected to the power source and data processing units by cables, which tether the patients. The researchers plan to ultimately make everything wearable.

“We are exploring all kinds of opportunities,” Xu says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)