A Visit to Seoul Brings Our Writer Face-to-Face With the Future of Robots

In the world’s most futuristic city, a tech-obsessed novelist confronts the invasion of mesmerizing machines

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/41/df413ccd-cf2f-45ea-886b-b037c07c1c47/jun2017_e10_robots.jpg)

The best part of a 14-hour flight from New York to Seoul is the chance to catch up on South Korea’s over-the-top and utterly addictive television shows. “Hair Transplant Day” is about a young man who believes he can’t get a job because he’s going slightly bald and has to resort to criminal measures such as extortion to raise funds for a hair transplant. “It’s a matter of survival for me,” the hero cries after a friend tells him that his baldness is “blinding.” “Why should I live like this, being less than perfect?”

Striving for perfection in mind, body and spirit is a Korean way of life, and the cult of endless self-improvement begins as early as the hagwons, the cram schools that keep the nation’s children miserable and sleep-deprived, and sends a sizable portion of the population under the plastic surgeon’s knife. If The Great Gatsby were written today, the hero’s last name would be Kim or Park. And as though human competition isn’t enough, when I land in Seoul I learn that Korea’s top Go champion—Go is a mind-bendingly complex strategic board game played in East Asia—has been roundly beaten by a computer program called AlphaGo, designed by Google DeepMind, based in London, one of the world’s leading developers of artificial intelligence.

The country I encounter is in a mild state of shock. The tournament is shown endlessly on monitors in the Seoul subway. Few had expected the software to win, but what surprised people most was the program’s bold originality and unpredictable, unorthodox play. AlphaGo wasn’t just mining the play of past Go masters—it was inventing a strategy of its own. This was not your grandfather’s artificial intelligence. The Korean newspapers were alarmed in the way only Korean newspapers can be. As the Korea Herald blared: “Reality check: Korea cannot afford to fall behind competitors in AI.” The Korea Times took a slightly more philosophical tone, asking, “Can AlphaGo cry?”

Probably not. But I have come to South Korea to find out just how close humanity is to transforming everyday life by relying on artificial intelligence and the robots that increasingly possess it, and by insinuating smart technology into every aspect of life, bit by bit. Fifty years ago, the country was among the poorest on earth, devastated after a war with North Korea. Today South Korea feels like an outpost from the future, while its conjoined twin remains trapped inside a funhouse mirror, unable to function as a modern society, pouring everything it has into missile tests and bellicose foreign policy. Just 35 miles south of the fragile DMZ, you’ll find bins that ask you (very politely) to fill them with trash, and automated smart apartments that anticipate your every need. I have come to meet Hubo, a charming humanoid robot that blew away international competition at the last Robotics Challenge hosted by the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency, or Darpa, the high-tech U.S. military research agency, and along the way visit a cutting-edge research institute designing robotic exoskeletons that wouldn’t seem out of place in a Michael Bay movie and hint at the strange next steps humans might take on our evolutionary journey: the convergence of humanity and technology.

**********

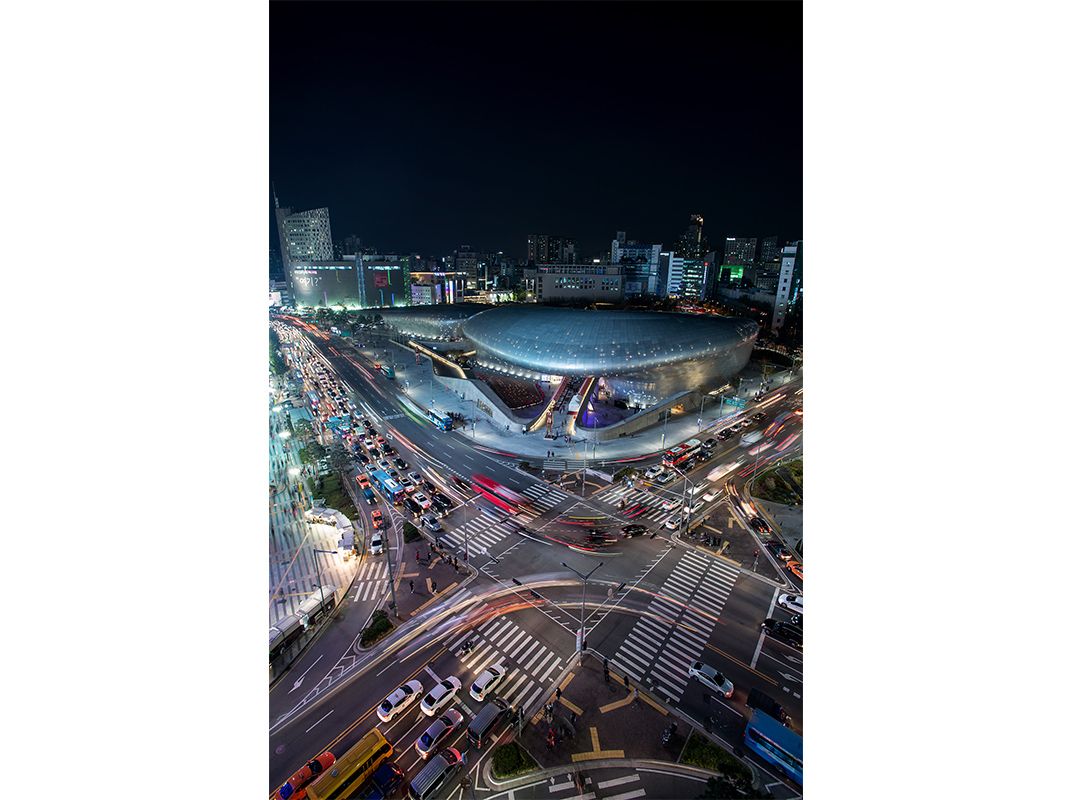

Seoul is a place that veers between utopia and dystopia with alarming speed. The city sleeps less than even New York, and its permanent wakefulness leaves it haggard, in desperate need of a hair transplant. Driving in from the airport, you get the feeling that Seoul never really ends. The sprawling metropolitan area tentacles in every direction, with a population of 25 million residents, which means that one out of every two South Korean citizens lives somewhere in greater Seoul.

And yet to get around the city is a dream, as long as you avoid taking a taxi during rush hour from the historic northern neighborhoods over the Han River to wealthy Gangnam (popularized by Psy and his horsey dance-music video), as the cabbie invariably blasts Roy Orbison on the stereo, an obsession I never quite figure out. I dare you to find a better subway system in the known universe: spotless, efficient, ubiquitous, with WiFi so strong my fingers can’t keep up with my thoughts. At all times of the day, bleary-eyed commuters candy-crush it to work, school, hagwon private schools. Over the course of an entire week, I witness only three people reading a print-and-paper book on the subway, and one of those is a guide to winning violin competitions.

Above us, high-resolution monitors show mournful subway evacuation instructions: People rush out of a stranded subway car as smoke approaches; a tragically beautiful woman in a wheelchair can’t escape onto the tracks and presumably dies. But no one watches the carnage. The woman next to me, her face shrouded by magenta-dyed hair, shoots out an endless stream of emojis and selfies as we approach Gangnam Station. I expect her to be a teenager, but when she gets up to exit, I realize she must be well into her 50s.

Full disclosure: I am myself not immune to the pleasures of advanced technology. At home, in New York, my toilet is a Japanese Toto Washlet with heating and bidet functions. But the Smartlet from Korea’s Daelim puts my potty to shame. It has a control panel with close to 20 buttons, the function of some of which—a tongue depressor beneath three diamonds?—I can’t even guess.

I encounter the new Smartlet while touring the latest in Seoul’s smart-living apartments with a real estate broker who introduces herself as Lauren, and whose superb English was honed at the University of Texas at Austin. Some of the most advanced apartments have been developed by a company called Raemian, the property division of the mighty Samsung. Koreans sometimes refer to their country as the Republic of Samsung, which seems ironically fitting now that a scandal involving the conglomerate brought down the country’s president.

The Raemian buildings are buffed, gleaming examples of what Lauren continually refers to as the “Internet of Things.” When your car pulls into the building’s garage, a sensor reads your license plate and lets your host know that you have arrived. Another feature monitors the weather forecasts and warns you to take your umbrella. An Internet-connected kitchen monitor can call up your favorite cookbook to remind you how to make the world’s best piping bowl of kimchi jigae. If you’re a resident or a trusted guest, facial recognition software will scan your visage and let you in. And, of course, the Smartlet toilet is fully Bluetooth accessible, so if you need to wirelessly open the door, summon your car, order an elevator, and scan a visitor’s face, all from the comfort of your bathroom stall, you can. If there’s a better example of the “Internet of Things,” I have yet to see it.

Across the river in Gangnam, I visit Raemian’s showroom, where I am told that each available apartment has a waiting list of 14 people, with the stratospheric prices rivaling those in New York or San Francisco. The newest apartment owners wear wristbands that allow them to open doors and access services in the building. The technology works both ways: In the apartments themselves, you can check in on all your family members through GPS tracking. (Less sinisterly, the control panel will also flash red when you use too much hot water.) I ask my chaperone Sunny Park, a reporter for Chosun Ilbo, a major national newspaper, whether there is any resistance to the continued diminution of privacy. “They don’t mind Big Brother,” she tells me of South Korea’s plugged-in citizens. Sunny, of a slightly older generation, admits that she can sometimes run into trouble navigating the brave new world of Korean real estate. “I once stayed in an apartment that was too smart for me,” she says. “I couldn’t figure out how to get water out of the tap.”

Remember the hero of “Hair Transplant Day” who cries out, “Why should I live like this, being less than perfect?” The automation of society seems to feed directly into the longing for perfection; a machine will simply do things better and more efficiently, whether scanning your license plate or annihilating you at a Go tournament. Walking around a pristine tower complex in Gangnam, I see perfect men toting golf bags and perfect women toting children to their evening cram sessions to bolster their chances of outcompeting their peers for spots in the country’s prestigious universities. I see faces out of science fiction, with double-eyelid surgery (adding a crease is supposed to make the eyes look larger) and the newly popular chin-shaving surgery; one well-earned nickname for Seoul, after all, is the “Plastic Surgery Capital of the World.” I see Ferrari’d parking lots and immaculately appointed schoolgirls nearly buckling under the weight of giant school bags in one hand and giant shopping bags in the other. I see a restaurant named, without any apparent irony, “You.”

Despite all that perfection, though, the mood is not one of luxury and happy success but of exhaustion and insecurity. The gadget-festooned apartments are spare and tasteful to within an inch of their life. They may come prestocked with Pink Floyd boxed sets, guides to Bordeaux wineries, a lone piece of Christie’s-bought art—a style of home décor that might be called “Characterville,” which is in fact the name of one Raemian building I come across. Of course, it betrays no character.

Back in the Raemian showroom, I see a building monitor showing a pair of elderly parents. When the system recognizes your parents’ arrival in the building, their photo will flash on your screen. The “parents” in this particular video are smiling, gregarious, perfectly coiffed and impervious to history. One gets the sense they never existed, that they too are just a figment in the imagination of some especially clever new Samsung machine.

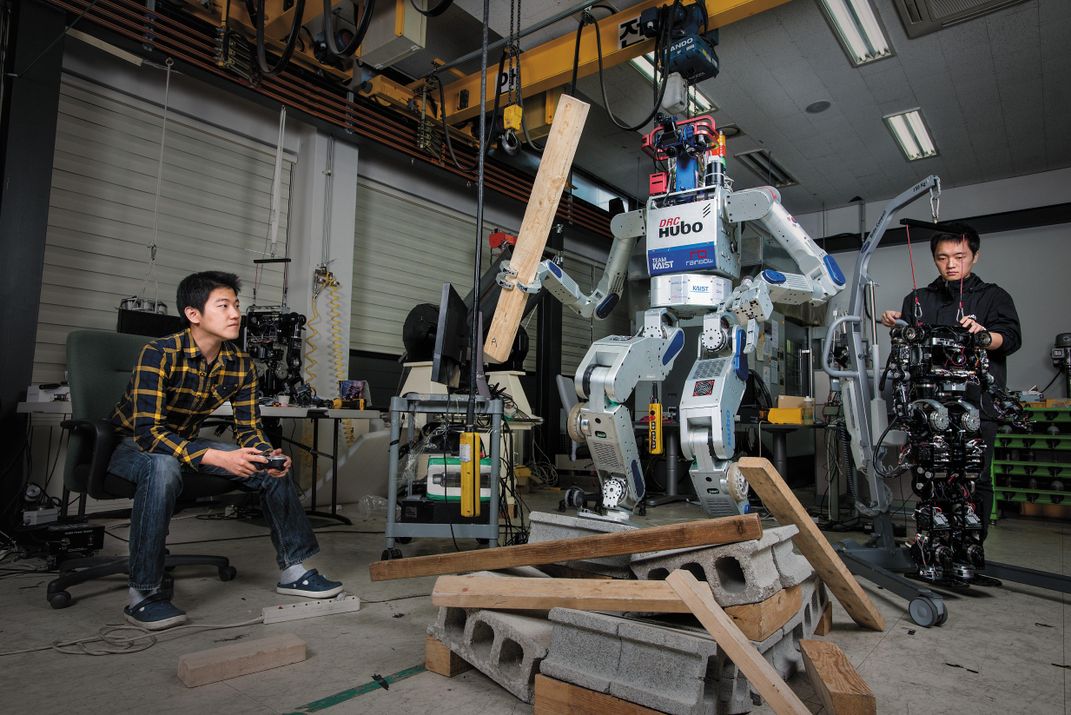

One morning I take a gleaming high-speed train an hour south of the city to meet Hubo the Robot, which lives at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, or KAIST, inevitably known as the MIT of Korea. Hubo is descended from a family of robots that his dad, a roboticist named Oh Jun-ho, has been working on for 15 years. Hubo’s the fifth generation of his kind—a 5-foot-7, 200-pound silver humanoid made of lightweight aircraft aluminum. He has two arms and two legs, and in place of a head he has a camera and lidar, a laser-light surveying technology that allows him to model the 3-D topography of his environment in real time. But part of the genius of Hubo’s design is that while he can walk like a biped when he needs to, he can also get down on his knees, which are equipped with wheels, and essentially transform himself into a slow-rolling vehicle—a much simpler and quicker way for a lumbering automaton to get around.

Winning the 2015 Darpa challenge and its $2 million top prize was no small feat, and it made the genial Professor Oh a rock star at the university. Twenty-five teams from the likes of Carnegie Mellon, MIT and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory entered the competition, which was designed to simulate a disaster scenario like the meltdown at Japan’s Fukushima nuclear power plant in 2011. At Fukushima, the engineers had to flee before they could completely shut down the plant, and it was a month before a pair of remote-controlled robots could enter the plant and begin to assess radiation levels.

Darpa hoped to drive innovation to improve robot capabilities in that kind of scenario, and operated on the premise that robots with some measure of human-like facility for movement and autonomous problem-solving would best be able to do work that humans couldn’t, saving lives. “We believe that the humanoid robot is the best option to work in the human’s living environment,” Oh says. Although specific tasks may well call for specialized robots—self-driving Ubers, Amazon delivery-drones, nuclear plant disaster valve-turners—a humanoid robot, Oh says, is “the only robot that can solve all the general problems” that people may need to solve, from navigating changing terrain to manipulating small objects.

Oh, a dapper man with round spectacles, a high forehead and as friendly a grin as you are likely to come across, explains that at the Darpa challenge, each robot had to complete a set of tasks that real disaster-response bots might face, like climbing stairs, turning a valve, opening a door, negotiating an obstacle course laden with debris, and driving a vehicle. Hubo drives much the way a self-driving car does, according to Oh: He scans the road around him, looking out for obstacles and guiding himself toward a destination programmed by his human masters, who, as a part of the competition’s design, were stationed more than 500 yards away, and had deliberately unreliable wireless access to their avatars, as they might during a real disaster. Although he can execute a given task autonomously, Hubo still needs to be told which task to execute, and when.

One such task at Darpa required robots to exit the vehicle after finishing their drive. It may sound simple, but we humans are quite used to jumping out of a cab; a robot needs to break the task down into many component parts, and Hubo does that, as he does all the tasks asked of him, by following a script—a basic set of commands—painstakingly written and programmed by Oh and his colleagues. To climb out of a car, he first lifts his arms to find the car’s frame, then grabs hold of it and discerns the right amount of pressure to apply before maneuvering the rest of his bulk out of the vehicle without falling. I’ve watched several of the larger characters on “The Sopranos” get out of their Cadillacs in the exact same way.

But Oh explains it’s especially tricky, and Hubo’s success sets him apart: Most humanoid robots would rely too much on their arms, which are often made to be rigid for durability and strength, and in the process risk breaking something off—a finger, a hand, sometimes even the whole metal limb. Or they might overcompensate by using the strength of their legs to get out and then never quite catch their balance once they’re outside, and tip over.

Hubo has what Oh describes as a reactive or “passive” arm—in this case, it’s really there for nothing more than light stability. Part of Hubo’s special intuition is to recognize how to use his component parts differently based on the specific task in front of him. So when he has to execute a vehicle exit, and reaches up to grab the frame of the car, he’s simply bracing himself before, as Oh puts it, “jumping” out of the car. “It’s the same for a person, actually,” Oh says. “If you try to get out from the vehicle using your arm, it’s very hard. You’re better to relax your arm and just jump out.” It’s clearly a feature Oh is proud of, beaming like a happy grandfather watching a year-old grandchild teach himself to push himself upright and stand on his own two legs. “It looks very simple, but it’s very difficult to achieve,” he observes.

This past January, KAIST inaugurated a new, state-funded Humanoid Robot Research Center, with Oh at the helm, and Oh’s lab is now developing two new versions of Hubo: One is much like the Darpa winner but more “robust and user-friendly,” Oh says. The lab’s immediate goal is to bestow this new Hubo with total autonomy—within the constraints of set tasks, of course, like the Darpa challenge, so basically a Hubo with an intelligence upgrade that gets rid of the need for operators. The other prototype might lack those smarts, says Oh, but he will be designed for physical agility and speed, like the impressive Atlas robot in development by the American company Boston Dynamics. “We are dreaming of designing this kind of robot,” says Oh.

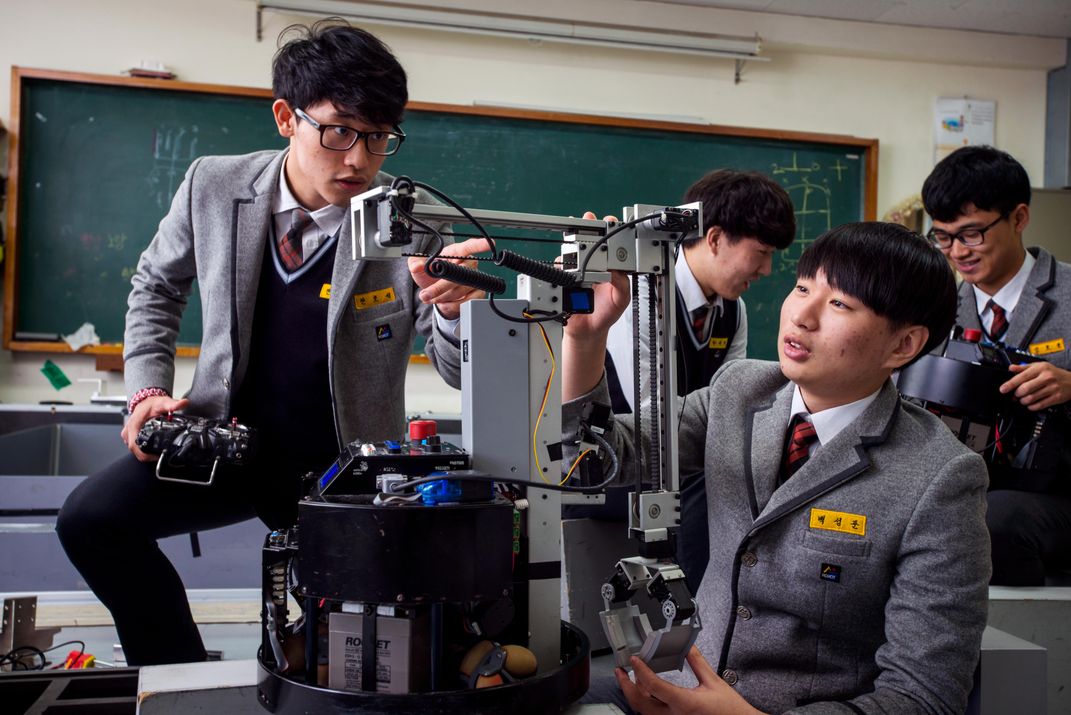

I ask Oh why South Korea, of all countries, got so good at technological innovation. His answer is quite unexpected. “We do not have a long history of technological involvement, like Western countries, where science has generated bad things, like mass homicide,” he says. “For us, science is all good things. It creates jobs, it creates convenience.” Oh explains that although Korea was industrialized only in the 1980s, very late by comparison with the West and Japan, the government has made huge investments in scientific research and has been funding key growth areas like flat-screen displays, and with enormous success: There’s a good chance your flat screen is made by Samsung or LG, the world’s two top sellers, which together account for nearly a third of all TVs sold. Around the year 2000, the government decided that robotics was a key future industry, and began to fund serious research.

We talk about the rumored possibility of using robots in a war setting, perhaps in the demilitarized zone between South and North Korea. “It’s too dangerous,” Oh says, which is another answer I was not expecting. He tells me that he believes robots should be programmed with intelligence levels in inverse proportion to their physical strength, as a check on the damage they might do if something goes wrong. “If you have a strong and fast robot with a high level of intelligence, he may kill you,” Oh says. “On the other hand, if he moves only as programmed, then there’s no autonomy,” shrinking his usefulness and creativity. So one compromise is a robot like Hubo: strong but not too strong, smart but not too smart.

Oh offers me the opportunity to spend some quality time with Hubo. A group of graduate students wearing matching Adidas “Hubo Labs” jackets unhook the silver robot from the meat-hook-like device on which he spends his off-hours, and I watch them power him up, their monitor reading out two conditions for Hubo: “Robot safe” and “Robot unsafe.”

Proudly stenciled with the words “Team Kaist” on his torso and the South Korean flag on his back, Hubo gamely faces up to the challenge of the day, climbing over a pile of bricks sticking out at all angles. Like a toddler just finding his legs, Hubo takes his time, his camera scanning each difficult step, his torso swiveling and legs moving accordingly. (Like a character out of a horror movie, Hubo can swivel his torso a full 180 degrees—scary, but possibly useful.) Hubo is the ultimate risk assessor, which explains how he could climb a set of stairs backward at Darpa and emerge from the competition without falling a single time. (Robots falling down tragicomically at the competition became a minor internet meme during the event.) After finishing his tasks, Hubo struck something of a yoga pose and did a brief victory two-step.

It’s hard to mistake Hubo for a humanoid along the lines of the “replicants” from Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (despite his good looks, he’s no Rutger Hauer), and, as I’ve mentioned before, his head is basically a camera. But it’s still hard not to find him endearing, which may be true of our interactions with robots in general. When the non-Hubo robots at the Darpa competition fell over, the audience cried out as if the machines were human beings. As technology advances, a social role for robots, such as providing services for the elderly (perhaps especially in rapidly aging societies like Korea and Japan), may well mean not just offering basic care but also simulating true companionship. And that may be just the beginning of the emotional relationships we’ll build with them. Will robots ever feel the same sympathy for us when we stumble and fall? Indeed, can AlphaGo cry? These questions may seem premature today, but I doubt they will be so in a decade. When I ask Oh about the future, he does not hesitate: “Everything will be roboticized,” he says.

**********

Another immaculate high-speed train whisks me across Korea to the industrial seaside town of Pohang, home to the Korea Institute of Robot and Convergence. The word “convergence” is especially loaded, with its suggestion that humankind and Hubokind are destined someday to become one. The institute is a friendly place gleaming with optimism. As I await a pair of researchers, I notice a magazine called the Journal of Happy Scientists & Engineers, and true to its promise, it is filled with page after page of grinning scientists. I’m reminded of what Oh says: “For us, science is all good things.”

Schoolboys in owlish glasses run around the airy first-floor museum, with features such as a quartet of tiny robots dancing to Psy’s “Gangnam Style” with the precision of a top K-pop girl band. But the really interesting stuff lies ahead in the exhibits that show the full range of the institute’s robot imagination. There’s Piro, an underwater robot that can clean river basins and coastal areas, a necessity for newly industrializing parts of Asia. There’s Windoro, a window-cleaning robot already in use in Europe, which attaches to skyscraper windows using magnetic force and safely does the job still relegated elsewhere to very brave humans. There is a pet dog robot named Jenibo and a quadruped robot that might serve in some guard dog-like capacity. There’s a kind of horse robot, which simulates the movements of an actual horse for its human rider. And, just when it can’t get any stranger or more amazing, there’s a kind of bull robot, still in development, which can perform eight actions a bullfighter would encounter, including head-hitting, shoving, horn-hitting, neck-hitting, side-hitting and lifting. An entity called the Cheongdo Bullfighting Theme Park already seems to have dibs on this particular mechanized wonder.

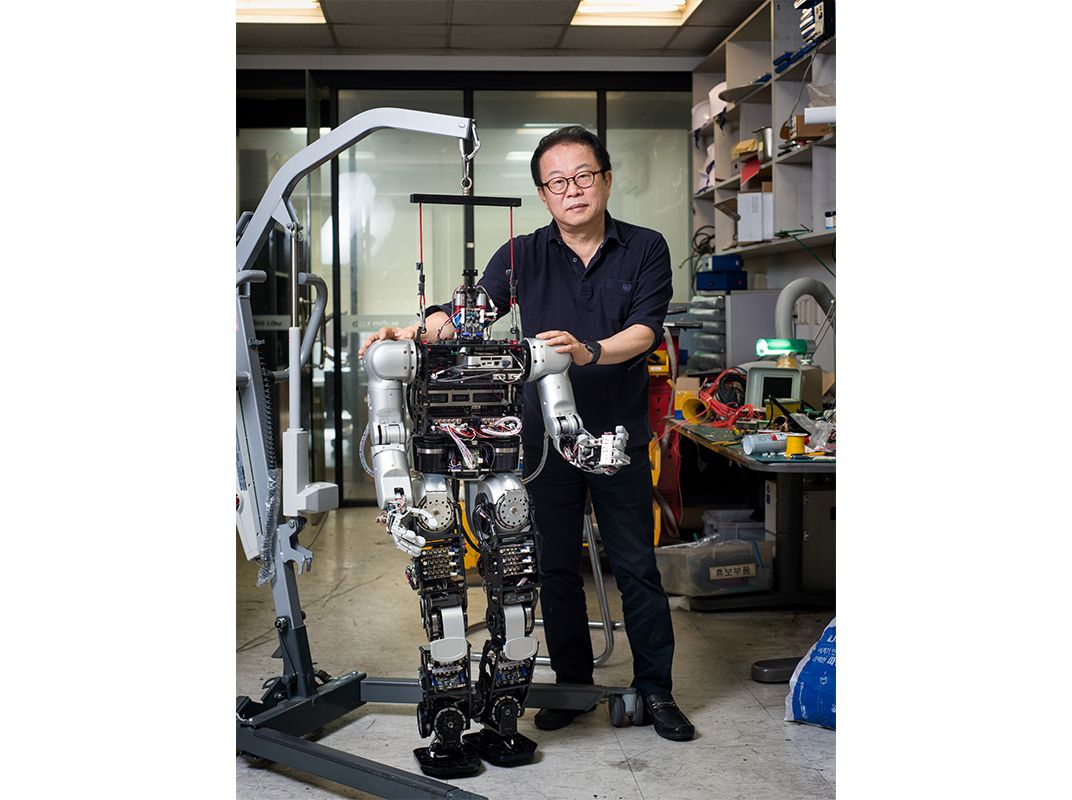

I ask Hyun-joon Chung, a young University of Iowa-educated researcher at the institute, why he thinks Korea excels at technology. “We have no natural resources,” he tells me, “so we have to do these things for ourselves.” Still, there’s one resource that has long dominated the area around Pohang, which is steel. The city is home to Posco, one of the world’s largest steelmakers. And this has given birth to one of the institute’s most interesting and promising inventions, a blue exoskeleton that fits around a steelworker’s body and acts as a kind of power-assist to help the worker perform labor-intensive tasks. This quasi-robot is already in use in Posco’s steel mills and is the kind of human-machine convergence that actually makes sense to me.

As Posco’s workers age, it allows them in their 50s, 60s and beyond to continue performing tasks that require great physical strength. Instead of robots providing mindless company to seniors—think of Paro, Japan’s famous therapeutic seal robot for the elderly, already a punch line on “The Simpsons”—the institute’s exoskeleton allows seniors to stay in the workforce longer, presuming they want to. This may be the one case of robots helping to keep manufacturing plant workers employed, instead of seeing them packed off to a lifetime of hugging artificial seals.

After my visit, at a little stand near the space-age train station, an older woman beneath a profound perm dishes out the most delicious bibimbap I’ve ever had, a riot of flavor and texture whose chunks of fresh crab remind me that industrial Pohang is actually somewhere near the sea. I watch an older woman outside the station who is dressed in a black jumpsuit with a matching black cap power-walking through a vast stretch of desolate scrubland, like a scene out of a Fellini movie. Above her are rows of newly constructed utilitarian apartment blocks the Koreans call “matchboxes.” Suddenly, I am reminded of the famous quote by the science fiction novelist William Gibson: “The future is already here. It’s just not very evenly distributed.”

**********

When I was a kid addicted to stories about spaceships and aliens, one of my favorite magazines was called Analog Science Fiction and Fact. Today, Science Fiction and Fact could be the motto for South Korea, a place where the future rushes into the present completely heedless of the past. So taking this phantasmagoric wonderland as an example, what will our world look like a generation or two from now? For one thing, we will look great. Forget that hair transplant. The cult of perfection will extend to every part of us, and the cosmetic-surgery bots will chisel us and suck out our fat and give us as many eyelids as we desire. Our grandchildren will be born perfect; all the criteria for their genetic makeup will be determined in utero. We will look perfect, but inside we will be completely stressed out and worried about our place (and our children’s place) in the pecking order, because even our belt buckles will come equipped with the kind of AI that could beat us at three-dimensional chess while reciting Shakespeare’s sonnets and singing the blues in perfect pitch. And so our beautiful selves will be constantly worried about what contributions we will make to society, given that all cognitive tasks will already be distributed to devices small enough to perch at the edge of our fingernails.

As the great rush of technology envelops us and makes us feel as small as the stars used to make us feel when we looked up at the primitive sky, we will be using our Samsung NewBrainStem 2.0 to send out streams of emojis to our aging friends, hoping to connect to someone analog who won’t beat us at Go in the blink of an eye, a fellow traveler in the mundane world of flesh and cartilage. Others of us, less fortunate, will be worried about our very existence, as armies of Hubos, built without the safeguards developed by kindly scientists like Professor Oh, rampage across the earth. And of course the balance of power will look nothing like today; truly, the future will belong to societies—often small societies like South Korea and Taiwan—that invest in innovation to make their wildest techno-dreams a reality. Can you picture the rise of the Empire of Estonia, ruled by a pensive but decisive talking toilet? I can.

Spending a week in Seoul easily brings to mind some of the great science fiction movies—Blade Runner, Code 46, Gattaca, The Matrix. But the movie I kept thinking about most of all was Close Encounters of the Third Kind. It’s not that aliens are about to descend on Gangnam, demanding that Psy perform his patented horsey dance for them. It’s that successive generations of post-humans, all-knowing, all-seeing, fully-hair-transplanted cyborgs will make us feel like we’ve encountered a new superior, if highly depressed, civilization, creatures whose benevolence or lack thereof may well determine the future of our race in the flash of an algorithm, if not the blast of an atom. Or maybe they’ll be us.

**********

One day, I take the train out to Inwangsan Mountain, which rises to the west of Seoul and offers spectacular if smoggy views of the metropolis. On the mountain you can visit with an eclectic group of free-range shamans, known as mudangs, who predate Buddhism and Christianity and act as intermediaries between humans and the spirit world and for steep prices will invoke spirits who may foretell the future, cure disease and increase prosperity. On this particular day the mudangs are women dressed in puffy jackets against the early March cold, tearing strips of colored sheets that are associated with particular spirits. White is connected to the all-important heaven spirit, red the mountain spirit; yellow represents ancestors, and green represents the anxious spirits. (If I could afford the shamans’ fees, I would definitely go with green.) Korea may be a society where nearly every aspect of human interaction is now mediated by technology, and yet turning to the spirits of the heavens, mountains and honored ancestors in this environment makes a kind of sense. Technology bestows efficiency and connectivity but rarely contentment, self-knowledge or that rare elusive quality, happiness. The GPS on the newest smartphone tells us where we are, but not who we are.

The Seonbawi, or “Zen rock,” is a spectacular weather-eroded rock formation that looks like two robed monks, who are said to guard the city. Seonbawi is also where women come to pray for fertility, often laden with food offerings for the spirits. (Sun Chips seem to be in abundance on the day I visit.) The women bow and pray intently, and one young worshiper, in a thick puffy jacket and a woolen cap, seems especially focused upon her task. I notice that squarely in the center of her prayer mat she has propped up an iPhone.

Later I ask some friends why this particular ritual was accompanied by this ubiquitous piece of technology. One tells me that the young woman was probably recording her prayer, to prove to her mother-in-law, who is presumably angry that she hasn’t produced any children, that she actually went to the fertility rock and prayed for hours on end. Another companion suggests that the phone belonged to a friend who is having trouble conceiving, and that by bringing it along, the woman is creating a connection between the timeless and immortal spirits and her childless friend. This is the explanation I like the most. The young lady journeys out from her city of 25 million plugged-in residents to spend hours on a mountaintop in the cold, promoting her friend’s dreams, hands clasped tightly in the act of prayer. In front of her, a giant and timeless weather-beaten rock and a small electronic device perched on a prayer mat steer her gently into the imperfect world to come.

Related Reads

Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future