Want to Learn Cherokee? How About Ainu? This Startup Is Teaching Endangered Languages

Tribalingual founder Inky Gibbens explains how saving languages is a means of preserving different worldviews

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dc/cb/dccb64cc-35d5-45d4-8b1a-af1f3bedb801/world_languages.jpg)

Some linguists estimate that roughly half of the world’s 7,000 or so languages are on the verge of extinction. A language might die out when a small territory is forced to integrate with a ruling power, or in many other circumstances. But when it does, a bit of human history goes with it.

The UK-based startup Tribalingual is trying to prevent those types of sociolinguistic losses, offering classes that connect students with some of the few remaining speakers of endangered languages. Research has long proven that speaking multiple languages improves cognition and may even help ward off dementia as one ages. Bilingualism is also becoming a practical, necessary skill for navigating our increasingly globalized world. There are numerous reasons to want to study another language—even one that might be on the decline or endangered.

Smithsonian.com caught up with Inky Gibbens, Tribalingual’s founder, about her passion for saving dying languages and how language influences thought.

How did you become interested in endangered languages?

I originally come from Mongolia, but my maternal grandparents come from Siberia, from a place called Buryatia. I moved to the United Kingdom in my late teens, and in an effort to connect back with my ancestral roots, I became interested in learning the Buryat language. But through my research, I was horrified to find out that Buryat was actually classified by the United Nations as endangered. This means that the language will very soon die out and so too will the culture and traditions of the Buryat people. I couldn’t let that happen so I looked for ways to learn the language. However, I realized that there was no way I could do it online or with a teacher. I also realized that there were many others out there like myself, who were interested in learning about these unique cultures. So Tribalingual was born as the solution.

How do you think about the relationship between language and culture?

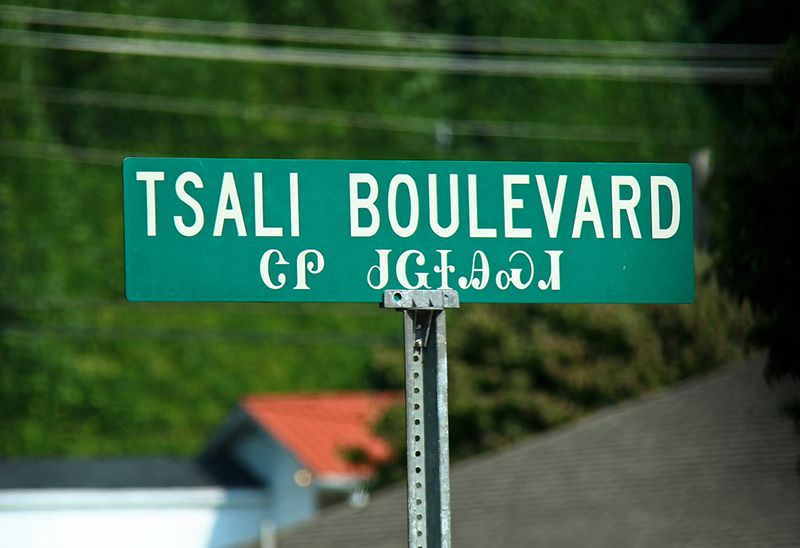

Numerous psychological and sociological studies document that different languages are not just different ways of communicating, they are different ways of thinking altogether. Learning to speak in other words actually means learning to think in other ways too. Did you know that the Mongolians do not have a word for ‘please,’ the Cherokee has no words for ‘hello’ or ‘goodbye’ or in Alamblak, a language of Papua New Guinea, there are only words for one, two, five and twenty and all others are built off of those? These different ways of thinking are part of shared human cultural heritage. And just like in art, architecture and culture, the rich variety of thought portrayed by these languages is part of what makes them so great.

Dominant world languages are all from a very small number of language families that all have shared—often European—ancestries. This really limits us. Only three percent of languages are spoken in Europe in total. In contrast, in Papua New Guinea, a hotbed of linguistic diversity, a tiny 0.2 percent of the world’s population speaks a massive 10 percent of the world’s languages. The main languages are not in any way representative of the full variety we have inherited.

Much of the world’s linguistic diversity is similarly concentrated in multiple small isolated communities. Today, partly owing to this technological revolution, we are living through a major extinction event. With one language stopping being spoken roughly every 14 days, it is estimated that within a century little more than half of the languages alive to today will remain so.

Culture, customs, traditions, stories, lullabies all make human existence valuable and rich. And when these languages die, the colorful tapestry of human civilization that we’ve all inherited becomes unraveled, bit by bit.

What’s your definition of an endangered language? What are the criteria for choosing which languages to include?

We only add languages that are either classified as endangered by UNESCO or are rare—languages which have very limited resources. We have a thorough assessment procedure that takes into account level of endangerment and revenue potential as well as policy support.

We have a list of languages that we target based on the level of endangerment and potential interest to customers. We then go out and see which we are able to develop easiest. This requires getting teachers, which dictates which of the languages on the list get adopted. Although we can define the direction, it’s not wholly up to us. Ultimately we need to find people who are passionate about preserving their culture but are also inspirational teachers.

How do you find instructors?

Speakers of languages who want us to add their languages frequently approach us. And once we have our list of languages we want to add, we will also go in search of speakers.

Who are your students?

We have spent zero on advertising. All our customers have come to us through social or earned media. This type of recognition is really important for us and ensures that the word gets out to people about Tribalingual. We have had students from all over the world learning with us. It really is incredible.

It’s important to understand that we’re dealing with vulnerable languages, so by definition these languages don’t have a large speaker base. Some of our languages have fewer than 15 speakers in the world. If we have a language with only 15 speakers and have five learners, we have increased the speaker base by a third and have made a huge impact in the revitalization of the language.

That being said, we’re seeing substantial demand for [less widely used but not endangered] languages like Yoruba and Mongolian. It’s mixed, but it is exactly as we are expecting.

Why do people want to learn these languages?

There are many different reasons why people want to learn our languages: the desire to learn something a bit different or to entrench oneself into communities during cultural travels. We’ve had customers who want to understand their heritage and history and learn the language of their ancestors. We’ve also been approached by a number of linguists and academics for whom our courses can support their research.

People also want to learn our languages for practical purposes. Yoruba is one of the big national languages of Nigeria. So if you’re going to Nigeria on business, it’s imperative to speak a little Yoruba but also as a sign of respect to the culture you’re about to live in, to also know what you should and shouldn’t do. Knowing this really puts you in favor with the locals. In fact, one of our students even managed to get a job in Japan having learned Ainu with us. It was a talking point during the interview, and the interviewers were amazed that someone had looked into the wider Japanese culture.

Would you walk me through what a student can expect to do in a course? How is it structured?

We have two types of courses—short and sweet four-week Explorer courses and longer, more intensive nine-week Globetrotter courses. The courses are split into weeks, and these weeks are split into manageable bite size chunks of information as text, audio or video.

Our courses are 50 percent language and 50 percent culture. By the end of the course, you should have basic communicative skills but also an understanding or insight into the culture of these communities: the songs, the poems and the stories these people have passed down from generation to generation. Our courses contain knowledge you won’t find anywhere else.

In addition to online content, you also have the option to Skype with a native speaker. So you fancy learning some Gangte? You can Skype with a teacher in the verdant hills of Manipur. Interested in Cherokee? Then you travel virtually to North Carolina.

The point is that we’re offering customers an authentic and immersive language and cultural experience of these cultures without them having to leave their home. Of course, once they’ve discovered us, many of our students go on to travel to these areas to further immerse themselves in the culture.

Why is it important to save these languages?

When languages die we lose an incredible opportunity to learn about our collective human psyche. This is because languages aren’t just ways of communicating, they are fundamentally ways of thinking as well. Let me illustrate this: a small tribe in the Amazon rainforest, known as the Piraha uses a language that doesn’t contain any words for defined numbers, like one, two or three. Instead, they simply use words like ‘all,’ ‘small amount,’ and ‘many’ to describe quantities.

Many people have been out to the Piraha and tried to teach them how to count, but all attempts have been unsuccessful. It turns out, if your language doesn’t have words for defined numbers, your worldview works without them. Another example: the language of the Amandowa tribe has no words for ‘time,’ ‘past,’ ‘present’,’ or ‘future.’ They don’t refer to the past or future, but they just live in the present. Even with something so fundamental to the existence as our passage through time, if your language doesn’t have the linguistic capacity to describe time, then your worldview works without it.

These cultures have something we simply cannot comprehend. And if we didn’t know all this, we would assume the world is just how we see it. But language isn’t just a vehicle for communication, it defines how we see the world. How many different ways are there of viewing the world? And how human really are we if we only understand one way of being human? The important thing for language conservation is that we’re barely scratching the surface of what these and other languages can teach us about the way human beings can look at the world. If they die now, we’ll simply never know.

What languages are you hoping to add to the course offerings next?

Our team is busy working with teachers on creating courses for Cherokee, Ladino, Javanese, Quechua and Tamazight. These are just a taste of what’s to come!

What’s next for Tribalingual? What do you ultimately hope to accomplish?

Our immediate priority is to contribute to some languages that are particularly vulnerable. To support that—because it demands resources—we are also developing product offerings with larger languages. In the interim, we hope to be offering widely accessible educational products, and eventually some novel platforms for learning and accessing culture and language.

We want, generations from now, for people to look back and say, ‘Wow, Tribalingual really made a difference.’

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/brittany_headshot_crop.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/brittany_headshot_crop.jpg)