Water Works

Taking up the family business, Philippe Cousteau campaigns to save our oceans and rivers

As our aluminum-hulled skiff makes its way up the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C., it hardly seems possible that we are on a tributary of the Potomac, within a mile of the United States Capitol. The shore is strewn with garbage; plastic bottles and Styrofoam cups float in the water. Along the riverbank, young volunteers from Earth Conservation Corps, an environmental group, are picking up trash. But there is nothing they can do about the raw sewage that pours into the river whenever rainwater overwhelms the District's sewer system.

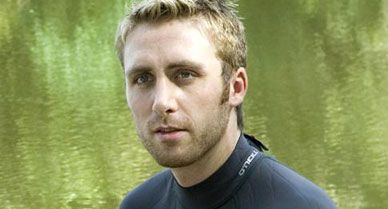

Philippe Cousteau, the 27-year-old grandson of Jacques, the marine cinematographer who introduced an entire generation to the wonders of the underwater world, stands near the middle of the boat recording the scene on a hand-held digital video camera. "People used to swim here, but now it's one of the most polluted rivers in the country," he says, noting that the Potomac flows into the Chesapeake Bay and from there, into the Atlantic. "We all live upstream from one another," he adds.

Philippe never knew his father—also named Philippe, who died in a plane accident in Portugal in 1979, a few months before his son's birth—but he knew his grandfather well and spent time with him during holidays. In addition to the sea, both Philippe's father and grandfather were interested in rivers; Jacques produced documentaries on the Amazon and the Mississippi; the elder Philippe's film about the Nile turned out to be his final project.

Although Cousteau is very much following in their swim fins—never, he says, did he consider doing anything else—Cousteau grew up not in France, as they did, but mainly in California and Connecticut. (His mother, Jan, is American.) And while a taste for adventure may be in his blood, he is almost as dedicated to snowboarding and rock climbing as to scuba diving. Earlier this year, he joined with the organizers of Vans Warped Tour, a hugely popular traveling international music festival, to expand its environmental awareness efforts. Cousteau hopes to create a "green section" on the tour's Web site and a video blog that shows band members speaking out about environmental issues.

Still, environmental documentaries remain Cousteau's primary focus; currently, he is working on a film that will examine the earth's oceans and waterways, a BBC/Discovery television production, to air in 2008. The documentary will emphasize humanity's impact on the natural world—and its stake in halting further degradation. "It can't just be about seeing humpback whales or trying to save fish and birds anymore," he says. "Now it's about saving us."

In spring 2006, a producer for the Animal Planet network asked Cousteau, their chief ocean correspondent, to team up with Steve Irwin, Australia's "crocodile hunter" on a documentary—Ocean's Deadliest—about great white sharks, sea snakes and other fearsome marine life, a project that led to tragedy and worldwide headlines. Last September, during filming near Australia's Great Barrier Reef, Irwin was killed when a stingray's barb pierced his heart. Cousteau, who was on a nearby boat, completed the documentary. The parallel to the loss he suffered as a child, he says, haunts him. "Steve left behind two children and they are going to grow up without a father. The circumstances are so similar."

Cousteau was a student at St. Andrews University in Scotland, when, in 2000, his family founded the Philippe Cousteau Foundation, which morphed into the Washington, D.C.-based environmental action group EarthEcho International in 2004. "Most people have this idea that government and industry are what really make a difference, but we [the public] are the only ones who can get them to change," Cousteau says. We all must change our ways, he says—from purchasing energy-efficient light bulbs to making saner transportation choices to getting kids involved.

That mission explains Cousteau's presence on the Anacostia. "These kids are making the connection," he says, "improving their communities by improving their environment." As we head downriver, he muses, "I don't want there to even be a green movement." In the next instant, he clarifies that statement: "I want it [instead] to be our way of life."

G. Bruce Knecht, formerly a Wall Street Journal reporter, is the author of Hooked: Pirates, Poaching and the Perfect Fish.