What Are You Flying Over? This App Will Tell You

Flyover Country uses maps and geology databases to identify features of the landscape as a plane flies over them, no Wifi necessary

:focal(396x179:397x180)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/bc/66bce2bd-5f24-4902-b8c6-de0c737292d1/airplane-over-mountains.jpg)

Shane Loeffler was returning home to Minnesota from the United Kingdom, flying over the glacial formations of Newfoundland and Quebec, when he had an idea.

“I was looking down from an airplane window and seeing this huge landscape and these geological features, and [wondering about] the landscape I was flying over,” he says.

What if, he thought, there was a guide to show fliers exactly what they’re seeing thousands of feet below?

One grant from the National Science Foundation later, and Loeffler, then a geology student at the University of Minnesota at Duluth, was on his way to developing this guide himself. His app, Flyover Country, is now available for free download.

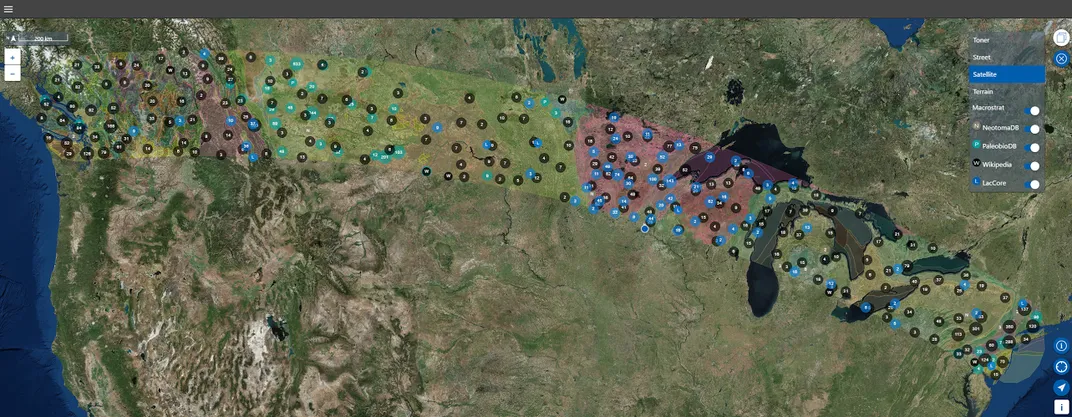

Flyover Country uses maps and data from various geological and paleontological databases to identify and give information on the landscape passing beneath a plane. The user will see features tagged on a map corresponding to the ground below. To explain the features in depth, the app relies on cached Wikipedia articles. Since it works solely with a phone’s GPS, there’s no need for a user to purchase in-flight wifi. Sitting in your window seat, you can peer down on natural features like glaciers and man-made features, such as mines, and read Wikipedia articles about them at the same time. If you're flying over an area where dinosaur bones have been discovered, you can read about that too. Curious about why the river below you bends the way it does? The app will tell you that as well.

Amy Myrbo, a geologist at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, and one of Loeffler’s co-developers on the app, recalls when Loeffler initially approached her with his idea.

“The way Shane put it, the airplane seat is sort of a planetarium for the Earth,” she says. “It’s a great way to inspire people to learn about the sciences.”

To that end, Loeffler, Myrbo and the rest of their team are working to add more data to the app. They hope scientists doing field work will soon be able to upload their findings directly, creating a living, ever-growing database of geology, paleontology and more.

“We have maybe a dozen more data sources that we’re going to be working with in the coming months,” Myrbo says. “Things like the chemistry of rocks, core samples from the oceans, information about earthquakes…[Scientists] are pretty excited to have their data get out there in a way that’s appealing, exciting and easy.”

Loeffler and Myrbo hope the app will be both a tool for scientists and a way for non-scientists to gain a better understanding of the Earth.

“I hope that people will get an idea of the connectedness of geology and weather and humans and see the scales of things,” Myrbo says. “There are these huge expanses of open spaces, but you can also see massive, massive evidence of human effects on the landscape, whether it’s dams backing up rivers, mines, deforestation or agriculture. There are these incredible natural features, but there is also a huge, ever-increasing human overprint to all of this.”

Of course, in order for the app to work, you need to be flying on a relatively cloudless day. The Western United States is best for clear flying, Loeffler says, recalling a flight over the Wind River Range in Wyoming during which he was able to read about glaciers on Wikipedia as he passed over them.

To keep a cloudy flight from being a total wash, the team hopes to engage a local meteorology enthusiast to write an article for the app about clouds, explaining how they’re affected by things like topography and wind patterns.

“There’s a lot going on in the troposphere above the Earth’s surface,” Myrbo says. “Clouds are not random. We’d love to do [something about] stars too.”

Learn more about this research and more at the Deep Carbon Observatory.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)