What the Housing Market in America Needs Is More Options

From granny pods to morphing apartments, the future of shelter is evolving

Think about the shape of home. Is it a three-bedroom, single-family dwelling with a scrap of yard? Maybe it’s you and your spouse and your kids—or maybe you share it with a handful of roommates. Or you cram yourself, your bicycle and your cat into a city studio where the rent is, naturally, too damn high.

But maybe a micro-loft with shared kitchen and living spaces would suit your needs better, or perhaps you’re a single parent who would love to share an apartment with another single parent. Take heart: these options are out there, and more of them are coming on the market all the time.

To showcase how the future of housing is evolving to accommodate America’s rapidly changing demographics, “Making Room: Housing for a Changing America,” a new exhibit at the National Building Museum, explores real-world examples that make use of clever designs and a deeper understanding of unmet demands in the housing market.

Once the dominant American demographic, nuclear families represent just 20 percent of American households today—but most of the housing stock is still built with that population in mind. So people living alone, empty-nesters and multi-generational families are having to jack-boot themselves into spaces that just don’t work well for them, and paying too much for the privilege.

“There are so many more options out there, but people often don’t know the right question to ask,” says Chrysanthe Broikos, curator of the new exhibit. “We’re so conditioned to think that a house is the right answer, with a master bedroom and smaller rooms for the kids. But what if you don’t have kids and you’d rather have two full baths and master bedrooms? We’re trying to show people that these options are actually out there.”

Anchored by a fully furnished, 1,000-square-foot apartment, the exhibit features more than two dozen real-world examples of communities, projects and individual buildings that are turning housing in America on its head.

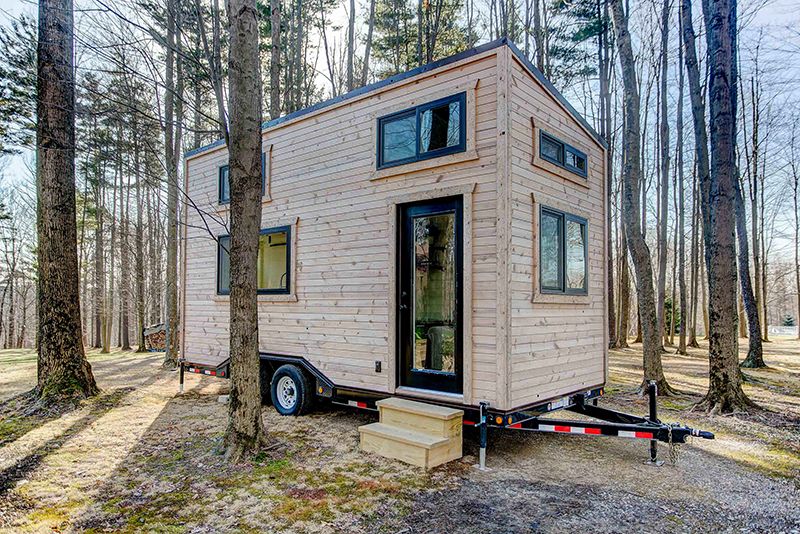

Take tiny houses, for example. They’ve been one of the hottest trends in housing for the last several years, with TV shows and do-it-yourself blogs going bananas for just how inventive people can get with a bite-sized living space. Community First!, a development located just outside the Austin city limits, takes the next logical step in tiny-house living. It’s an entire village made up of itty bitty houses—specifically intended to provide shelter for homeless and chronically disabled people.

There’s also WeLive, a converted office high rise in the Crystal City area of Arlington, Virginia. Though most of the 300- to 800-square-foot units have kitchens and are fully furnished, life here is more community-oriented. If you’re a recent transplant, the Sunday night dinners in the shared kitchen areas and common-space yoga classes here might be just the thing to help you make new friends and feel more at home in your new city.

Or say you’re a single parent, but can’t afford a decent place on your own, and apartment sharing with a non-parent roommate hasn’t worked well in the past. Now you can use an online matchmaker like CoAbode, a service specifically for single moms interested in easing the financial and time burdens by sharing a place with a fellow single mother.

And on the opposite end of the spectrum: the “granny pod.” Like a tiny house but equipped with features like touch-illuminated flooring, grab bars and sensors for vital sign monitoring, these stand-alone structures can be dropped right into a back yard. Grandma can have her privacy and independence, but with family or a caregiver close at hand should the need arise.

Broikos cast a wide net in her search for examples to feature in the exhibit, and says that only one of the featured projects, MicroPAD in San Francisco, is at the prototype stage. Projects were selected to showcase new ideas for sharing, aging-in-place, a variety of interpretations of “micro-“ scale living, and reconfigurable units and houses.

Zoning and use regulations have long been part of the problem, with cities and municipalities barring the conversion of old warehouses or market buildings into micro-loft developments due to minimum square-footage restrictions, or prohibiting “accessory dwelling units” like granny pods and tiny houses on single-family lots. That is starting to change, but slowly.

“For the money that is doled out for these projects, some of those formulas are so complicated,” Broikos says. “So as a developer, once you crack the formula and figure out how the money flows, it takes a lot to do something different. Loosening up the regulations and understanding how those need to change to encourage different kinds of housing for different needs is important.”

Former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, for instance, waived zoning requirements for the city’s first “micro-unit” development. Portland has been aggressively reshaping its regulations on accessory dwellings over the last two decades, while national homebuilding companies like Lennar, Pulte Homes and Ryland have been experimenting with floorplans that accommodate multiple generations or landlord-tenant arrangements.

One approach is to change how the interiors of spaces are used and viewed. After exploring an avenue of case studies on how the design of the physical structure of housing is changing, visitors can explore a full-scale model home to show how creatively interior space can be used even in a conventional floorplan where space is at a premium.

Designed by architect Pierluigi Colombo, the apartment is loaded with furniture and features that maximize livable space. The result is a dwelling that is more than just its square footage. Motorized and moveable sound-proof walls and ultra-slim Murphy beds that flip down over a sofa are just two of strategies demonstrated in the space-morphing model home within the exhibit. For visitors, docents will be on hand in the exhibit to help demonstrate how each piece works.

“A one-bedroom apartment in Manhattan can cost $1.5 million, so you could be very successful and still not be able to afford a very large space,” says Ron Barth, founder of Resource Furniture, whose double- and triple-duty pieces furnish the exhibits demo home. A two-foot-wide console table along one wall can be extended into a nine-foot dining trestle, the leaves for which are stored away in a nearby closet. In the kitchen, the granite-topped prep counter lowers to dining height at the touch of a button, removing the need for a separate dining table at all.

“More people are interested in sustainability these days, and with the cost of real estate being what it is, we saw an opening in the market,” Barth adds. “People need flexibility, for a living room to be able to become a guest room, and be an actual room. These things are out there, and there are more of them every year.”

Technology has been a big factor in the accelerated pace of new, innovative projects being built, or cities starting to open up their regulation books to take chances on nontraditional projects.

“This moment is different from, say, 10 years ago, because with all our tech today, with all our books and CDs on our phones, it’s actually easier to live in less space,” Broikos says. “The sharing economy is helping people realize that there are lots of different ways to get something done, and we’re beginning to see how technology and that sharing economy are impacting choices in building and living, too. This is a unique moment.”

“Making Room: Housing for a Changing America” runs through September 16, 2018, at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)