What is the Nine Millionth Patent?

The landmark announcement is part of the United States Patent and Trademark Office’s celebration of the 225th anniversary of the Patent Act

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6e/78/6e788066-c2c3-42a3-adc4-1e319df3c7a0/42-46419459.jpg)

Windshield washer fluid is one of those pesky car components that isn’t top of mind until it runs out. Matthew Carroll, an inventor in Jupiter, Florida, has found a way to keep a constant supply in the car.

His product, called WiperFill, recycles the rain. It collects rainwater, dew and melting snow and ice on a car's windshield and automatically replenishes a reservoir, where the water is filtered and mixed with concentrate pellets to make cleaning fluid or deicer. This particular idea is the latest of many that have made their way through the United States Patent and Trademark Office, and also happens to mark a major milestone as the nine millionth patent ever granted.

The Patent Act of 1790 was signed into law 225 years ago by President George Washington on April 10 of that year. The legislation was the first of its kind in American history, establishing a system for the government to evaluate inventions and determine whether an individual could own rights to the creation for a set period of time. The concept of a patent had existed in other countries, most notably in Italy and France, where inventors, or the guilds they were a part of, could apply to own and exclusively practice a particular technique. As early as 500 BCE, there is evidence of a patent-like system used in Greece to enable ownership of an idea for up to a year, establishing a relative monopoly on that product.

During the 16th century, the English monarchy was criticized for abusing the patent system, doling out patents to those willing to pay for them, thereby giving these parties exclusive rights and monopolies in certain industries. In the 1780s, under the Articles of Confederation, each state had the power to independently issue patents. But the 1790 Act created the first American system for patents that operated on a federal level. In England, the focus of patent law had been heavily on the benefits that new inventions provide society. In the U.S., the focus of the law shifted to highlight the patent as an inventor's property.

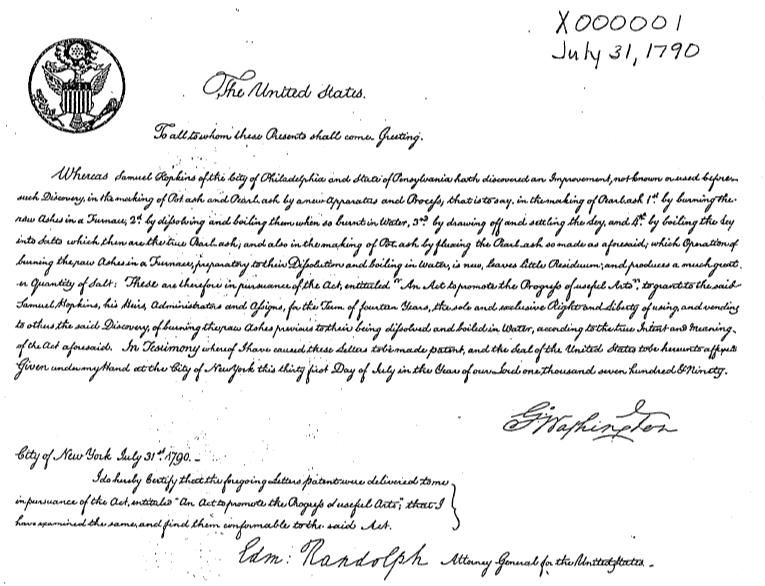

The Patent Act was momentous, because it acknowledged that rights to what is now known as "intellectual property" were something inventors possessed inherently and not a "privilege bestowed by a monarch." As part of the original law, a three-person board, made up of the Secretary of State, Secretary of War and Attorney General, was created to oversee patent approvals. Thomas Jefferson, who was Secretary of State at the time, served as the first ever patent examiner.

The law had stringent requirements, most notably that the exclusive board of high-level officials had to find “the invention or discovery sufficiently useful.” Jefferson and his two counterparts, Secretary of War Henry Knox and Attorney General Edmund Randolph, carefully inspected every submission. In order to obtain a patent, inventors had to provide a “specification, drawing or model” of their work along with a fee of $4 to $5. Patents were not to last for more than 14 years.

The first to pass the high bar set by the board was Samuel Hopkins of Philadelphia. He developed a new method for producing an ingredient in fertilizer and, on July 31, 1790, received a patent for “the making of Pot ash and Pearl ash by a new Apparatus and Process."

In 1793, the Patent Act was repealed, in part because a considerable backlog had accumulated due to the fact that each invention had to be evaluated with intense scrutiny by board members who had many other duties. The government implemented a new, more efficient process with the Patent Act of 1793 and the subsequent Patent Act 1836, which established the United States Patent Office. The Patent Office hired experts in the arts and sciences to review patent applications and determine "any new and useful art, machine, manufacture or composition of matter and any new and useful improvement on any art, machine, manufacture or composition of matter."

There are now two main kinds of patents: utlity and design. Utility patents are evaluated based on how an invention works and are granted for 20 years, while design patents protect the way an object looks for a period of 14 years. The USPTO amassed one million patents on August 8, 1911, with the invention of a new durable and puncture-resistant tire by Francis Holton of Akron, Ohio. One hundred years later, in August 2011, the eight millionth patent, for a visual prosthesis, was issued, and the rate at which patents were granted increased significantly. While more than 24 years passed between the one millionth and two millionth patent milestones, the eighth and ninth are only four years apart.

For some time, the United States, Canada and the Phillippines were the only countries that had a "first to invent" policy, requiring those who applied for patents to thoroughly document the process of developing the product, compared to the "first to file" laws in other places that issued patents to the first person to successfully complete the application. In 2013, the U.S. converted to a "first to file" law with the passage of the America Invents Act, although there is still some leeway for inventors to contest if they can provide ample evidence they created a product first. A "first to file" system is expected to bring U.S. law closer to that of the rest of the world and further expedite the patent process, with the influx of inventions in recent years. Apple, Google and other tech giants are filing patents for concepts before they know if, when and how they will apply them to products, which has led to numerous patent wars and criticism of the patent system.

Today, individuals can file a patent application online at the USPTO's website, where they can also search the millions of patents that have been submitted to date.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)