What Is a Maker Faire, Exactly?

Billed as the world’s greatest show and tell, the DIY extravaganza might just make a maker out of you

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/2e/152e07ec-4ff7-499b-aad8-84f8111cfc74/15253612130_f3a6344e5d_k.jpg)

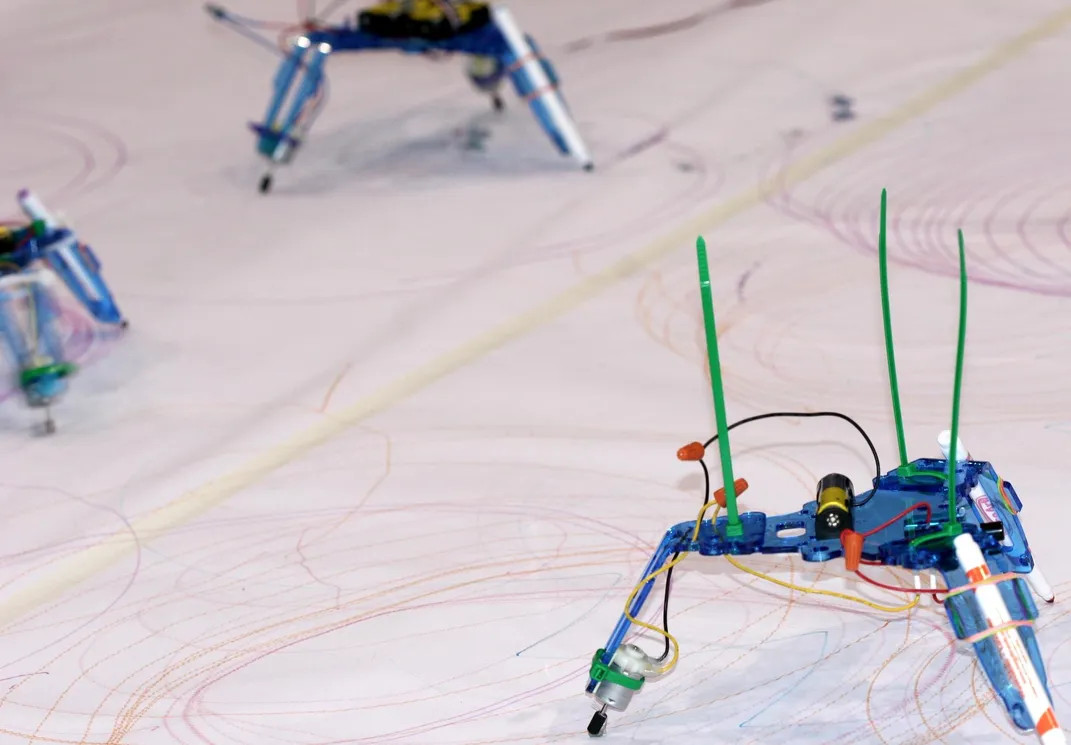

Brace yourself: When you walk into a Maker Faire, right alongside the LED-festooned robots you might see a giant cupcake bicycle, rocket-powered fairground rides or a pirate dance show. A bristling medieval-village signpost points you toward the soldering area, or the fire arts zone, or the fun bike. Or unicorns.

Equal parts steampunk convention, craft show and Bill Nye extravaganza, a Faire can be bewildering.

These bizarre bazaars are gleeful public displays of innovation and do-it-yourself inventiveness, and the only requirement for participants is that they make the contraptions themselves and want to make them accessible to others. When you visit a table, display or presentation, the guy controlling the fire spouting from his dragon car is the same dude who built the thing, usually from the ground up. He’ll probably tell you exactly how he made it happen, too.

But even the godfather of the Maker Faire phenomenon, Dale Dougherty, said it’s tough to explain what these gatherings fundamentally are.

“Faires are a celebration of making in our culture,” says Dougherty. “It’s experimentation and play. Most of the makers are creating something to interact with other people, or to get a reaction out of them.”

Dougherty publishes Make magazine and is the executive chairman of Maker Media, which sponsors the Faires in cities across the country, and increasingly, the globe. In 2014, there were 131 Faires around the world. Last weekend alone, Faires took place in Kiev, Ukraine; Hanover, Germany; and Vancouver, Canada. Next week there’s one in Shenzhen, China.

Dougherty himself is a maker mainly of edibles: wine, beer, plum jam and hot pepper sauce. But as a former vice president with O’Reilly Media, a company that earned its chops publishing books about the Internet and organizing tech conferences, he has long rubbed shoulders with innovators. (O’Reilly Media credits him with coining the term “Web 2.0” in the ‘90s.)

After starting Make in 2005, to feed people ideas for how to play with all the crazy tech coming out, Dougherty realized that there was an artificial loneliness to creating cool new stuff. Making was a solitary endeavor, and it didn’t have to be.

“I was meeting interesting makers, and I thought they would enjoy meeting each other,” he says. “It’s something we’re missing: You go to a museum and see objects from artists, but you don’t get to talk to them.”

The first Faire was held in San Mateo, California in 2006, and attracted around 20,000 people. Encouraged by the strong initial response, Dougherty and his team wrote a guide for others to use in their own communities. Shows are organized by volunteers, and promoted via word of mouth and social media. This year, over 140,000 people attended the annual two-day show in the Bay Area.

For an event to be an official Maker Faire, organizers do all their own outreach to find participants, though they may collaborate with larger entities, including local governments and universities. Planners go to lengths to include makers of all types: gardeners, cooks, artists, engineers, musicians, performers, local businesses and sponsors. Mini Faires are smaller, hyperlocal events that often lead to a city growing a larger Faire. Washington, D.C.’s National Maker Faire evolved from last year’s D.C. Mini Faire and White House Maker Faire.

After a few successful Faires, the “maker movement” was born. Dougherty’s vision is to create places where consumers and creators of art, technology and culture would be able to come together in a cohesive community.

“I like this raw conversation around how did you get that idea, where did you get those parts, what tools did you use, was it hard to make?” says Dougherty.

The way shows are populated by makers turns traditional conference planning on its head: Organizers look at what projects have been submitted, and design the event around that, usually into clustered “villages.” Individuals who don’t fit into a group aren’t ignored—the loner piñatas, cardboard sculptures and pet robots are given space as well. Sometimes, planners put two wildly different projects next to each other to see if the pairing spawns a new idea.

Artist Danny Scheible has created Tapagami, a growing conglomerate sculpture to which participants add objects made from masking tape. It is currently composed of 150,000 individual pieces. He is a veteran of several Bay Area Faires and says he was compelled to join in the fray because to do otherwise would be to miss out on the beginning of a new generation of ingenuity—kids acquire ideas at places like Maker Faire that inspire them. Plus, he says, he leaves each time feeling flush with new ideas for his own art.

"The Faire is like taking Burning Man, Disneyland and Silicon Valley and smashing them together," Scheible says. "It provides me with lifelong friends, and is one of the best places in the world to find people open to collaboration on projects. It motivates me to push my own work much further."

First and foremost, projects are hands-on and interactive. Though many efforts are whimsical and light-hearted, there are plenty of world changers: at the National Maker Faire, a group of Cornell University students are demonstrating their self-contained hydroponics grow box, while elsewhere, 3D Print for Health shows how scanning and printing tumors, bones, organs and other body parts can help patients become more involved in their own healthcare.

In Queens, where the World Maker Faire New York has just sent out its first call for participants for this year’s September event, co-organizer Nick Normal struggles for words to describe what being at a Faire is like. But what is clear is the wonder that people, pushed out of their comfort zones, experience as they visit the different project areas.

In 2014, attendees’ collective efforts in just one day resulted in Tick Tock the Croc, a 51-foot-long watercraft made of repurposed bike frames, complete with audio and lighting.

“Sometimes the parents are taken aback by the ability to take things apart, but their kids are diving right in,” Normal says. “It’s the full spectrum of humanity, saying, are we supposed to do this?”

At last year's Bay Area event, half of all attendees brought their children along. Faires are family friendly, and kids enjoy not being told to keep their hands off everything for a change. It's the exact opposite: children, as well as adults, are encouraged to build, tear down, touch, feel and experience.

The first full-blown Faire to be held in Washington, D.C., hosted by the University of the District of Columbia on June 12 and 13, follows a similar model as other shows by bringing together strongly regional influences. This means that there’s a heavy federal agency presence—tinkerers who happen to work in those places. The D.C. organizers actively ferreted out individuals from the United States Department of Agriculture, NASA, the Department of Homeland Security and the Smithsonian, as well as public schools and universities. But despite high agency participation, the D.C. gathering has the same primary goal as any other—to demystify electronics and remove the intimidation around tech wizardry.

“Everybody can be a maker,” says Brian Jepson, an organizer of the National Maker Faire. “Makers have gone from people who work in their garage to build something fun, to creating a fairly large market of products. The Faires provide these on-ramps where you’re going to go home and say, I have to do that. You don’t need to be an engineer or a programmer. You just have to want to do it.”

The National Maker Faire kicks off the White House’s Week of Making from June 12 through 18, which aims to highlight and encourage the development of technical skills, innovation and entrepreneurship.

At the 2014 White House Maker Faire, President Obama remarked on the weird and wonderful that popped up there—a robotic giraffe was a big hit—and recalled a time not too long ago when everything was DIY.

“Our parents and our grandparents created the world’s largest economy and strongest middle class not by buying stuff, but by building stuff,” he said at the event. “New tools and technologies are making the building of things easier than ever. Across our country, ordinary Americans are inventing incredible things, and then they’re able to bring them to these fairs. And you never know where this kind of enthusiasm and creativity and innovation could lead.”

Since then, 21 federal agencies announced eased access to startup grants, mentoring, training and manufacture permitting. During the 2015 Week of Making, the White House is pushing for an even greater commitment by universities, businesses, schools and libraries to make making easier. Together, the Smithsonian Institution and the United States Patent and Trademark Office, are answering the call by hosting an Innovation Festival on September 26 and 27 at the National Museum of American History, celebrating American innovation and inventors, and other programs that encourage making.

But even with this high-level endorsement, Dougherty is quick to point out that the gatherings aren’t corporate conventions or government-sponsored creations.

“It’s still very much grassroots,” Dougherty says. “It’s lots of people doing things, and somehow it’s come together as a movement. The secret is appreciating that it’s widely distributed and self-organized. I want people to get inspired by the makers they see, and say, ‘This is something I can do.’”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)