When Machines See

Giving computers vision, through pattern recognition algorithms, could one day make them better than doctors at spotting tumors and other health problems.

![]()

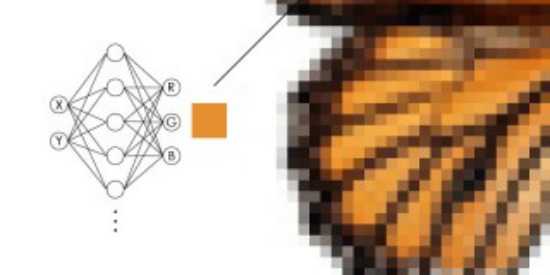

Pattern recognition of a butterfly wing. Image courtesy of Li Li

Here in Washington we have heard of this thing you call “advance planning,” but we are not yet ready to embrace it. A bit too futuristic.

Still, we can’t help but admire from afar those who attempt to predict what could happen more than a month from now. So I was impressed a few weeks ago when the big thinkers at IBM imagined the world five years hence and identified what they believe will be five areas of innovation that will have the greatest impact on our daily lives.

They’ve been doing this for a few years now, but this time the wonky whizzes followed a theme--the five human senses. Not that they’re saying that by 2018, we’ll all be able to see, hear and smell better, but rather that machines will–that by using quickly-evolving sensory and cognitive technologies, computers will accelerate their transformation from data retrieval and processing engines to thinking tools.

See a pattern?

Today, let’s deal with vision. It’a logical leap to assume that IBM might be referring to Google’s Project Glass. No question that it has redefined the role of glasses, from geeky accessory that helps us see better to combo smartphone/data dive device we’ll someday wear on our faces.

But that’s not what the IBMers are talking about. They’re focused on machine vision, specifically pattern recognition, whereby, through repeated exposure to images, computers are able to identify things.

As it turns out, Google happened to be involved in one of last year’s more notable pattern recognition experiments, a project in which a network of 1,000 computers using 16,000 processors was, after examining 10 million images from YouTube videos, able to teach itself what a cat looked like.

What made this particularly impressive is that the computers were able to do so without any human guidance about what to look for. All the learning was done through the machines working together to decide which features of cats merited their attention and which patterns mattered.

And that’s the model for how machines will learn vision. Here’s how John Smith, a senior manager in IBM’s Intelligent Information Management, explains it:

“Let’s say we wanted to teach a computer what a beach looks like. We would start by showing the computer many examples of beach scenes. The computer would turn those pictures into distinct features, such as color distributions, texture patterns, edge information, or motion information in the case of video. Then, the computer would begin to learn how to discriminate beach scenes from other scenes based on these different features. For instance, it would learn that for a beach scene, certain color distributions are typically found, compared to a downtown cityscape.”

How smart is smart?

Good for them. But face it, identifying a beach is pretty basic stuff for most of us humans. Could we be getting carried away about how much thinking machines will be able to do for us?

Gary Marcus, a psychology professor at New York University, thinks so. Writing recently on The New Yorker’s website, he concludes that while much progress has been made in what’s become known as “deep learning,” machines still have a long way to go before they should be considered truly intelligent.

“Realistically, deep learning is only part of the larger challenge of building intelligent machines. Such techniques lack ways of representing causal relationships (such as between diseases and their symptoms), and are likely to face challenges in acquiring abstract ideas like “sibling” or “identical to.” They have no obvious ways of performing logical inferences, and they are also still a long way from integrating abstract knowledge, such as information about what objects are, what they are for, and how they are typically used.”

The folks at IBM would no doubt acknowledge as much. Machine learning comes in steps, not leaps.

But they believe that within five years, deep learning will have taken enough forward steps that computers will, for instance, start playing a much bigger role in medical diagnosis, that they could actually become better than doctors when it comes to spotting tumors, blood clots or diseased tissue in MRIs, X-rays or CT scans.

And that could make a big difference in our lives.

Seeing is believing

Here are more ways machine vision is having an impact on our lives:

- Putting your best arm forward: Technology developed at the University of Pittsburgh uses pattern recognition to enable paraplegics to control a robotic arm with their brains.

- Your mouth says yes, but your brain says no: Researchers at Stanford found that using pattern recognition algorithms on MRI scans of brains could help them determine if someone actually had lower back pain or if they were faking it.

- When your moles are ready for their close ups: Last year a Romanian startup named SkinVision launched an iPhone app that allows people to take a picture of moles on their skin and then have SkinVision’s recognition software identify any irregularities and point out the risk level–without offering an actual diagnosis. Next step is to make it possible for people to send images of their skin directly to their dermatologist.

- Have I got a deal for you: Now under development is a marketing technology called Facedeals. It works like this: Once a camera at a store entrance recognizes you, you’re sent customized in-store deals on your smart phone. And yes, you’d have to opt in first.

- I’d know that seal anywhere: A computerized photo-ID system that uses pattern recognition is helping British scientists track gray seals, which have unique markings on their coats.

Video bonus: While we’re on the subject of artificial intelligence, here’s a robot swarm playing Beethoven, compliments of scientists at Georgia Tech. Bet you didn’t expect to see that today.

More from Smithsonian.com

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)