Without These Whistleblowers, We May Never Have Known the Full Extent of the Flint Water Crisis

A concerned mother and a renowned scientist spearheaded the investigation that exposed the dangers lurking in the water supply of the Michigan city

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/b3/bcb3fd80-8e76-4a34-a81c-3190f4223061/dec2016_d04_ingenuity-wr.jpg)

LeeAnne Walters and Marc Edwards perch next to each other on bar stools in a cluttered recording studio on the Virginia Tech campus in Blacksburg. “We proved that citizens and scientists working together could form a great alliance, and that grass-roots science can have a sky-high impact,” Walters says to the camera.

Walters, 38, is reading from a script and, compared with her usual blunt and no-nonsense delivery, sounds tentative. The video they’re recording is for a not-yet-named organization they’re trying to start, to bring ordinary folks and scientists together to fight for cleaner water and better public health standards.

Edwards, 52, is tall and rangy and slouches a bit. “It worked in Flint,” he says to the camera, “it will work across the United States.”

What worked in Flint, site of the most startling American public health failure in decades, was the duo’s uniquely potent combination of outraged persistence and scientific directness. Walters, a stay-at-home parent then living on the south side of Flint, and Edwards, a VT professor of civil and environmental engineering, showed that the city had allowed dangerous levels of lead and other toxic substances to leach into drinking water for a year and a half. Their work helped force Gov. Rick Snyder, who had denied there even was a problem, to finally deal with it. “We would be nowhere, absolutely nowhere, without LeeAnne and Marc,” says Mona Hanna-Attisha, a Michigan State University pediatrician and researcher who studies lead poisoning.

It was in December of 2014 that Walters’ tap water turned brown, then over the following months a rainbow of industrial colors—“light yellow to nasty, dark-looking cooking grease,” she recalls. She, her husband, Dennis, and their four children were afflicted by rashes, hair loss and abdominal pain. Gavin, then 3, all but stopped growing. In February 2015, Walters persuaded the city to test her tap water. “I got a frantic phone call from the water department telling me not to drink it, not to let the kids drink it, not to mix my kids’ juice with it,” she says.

Tests found lead at approximately seven times the legal limit of 15 parts per billion. Later analyses showed it spiking to 800 times the limit—equivalent, Edwards says, to toxic waste. Lead is an insidious poison linked to a variety of disorders, especially in children, including cognitive impairments and violent behavior.

Hundreds of other Flint residents also complained about nasty, unpotable water and health problems, but even then Flint officials insisted the lead problem was limited to the Walters’ household (though their pipes were plastic). At a City Council meeting, one Flint official intimated that Walters and her neighbors were spiking their own water just to draw attention to themselves. Walters called a nurse in the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services to ask about Gavin, whose preexisting health problems made him particularly susceptible to lead. “It’s just a few IQ points,” the nurse told her. “It’s not the end of the world.”

Walters, a high-school graduate trained as a medical assistant, spent months wading through technical documents about the Flint water system. She knew that the city, then financially distressed and run by a state-appointed manager, had switched its municipal water source from Detroit’s system, which draws from Lake Huron, to the Flint River, to save $5 million over two years. In the process, she found, corrosion control treatments mandated to prevent lead and other metals from leaching out of pipes had been omitted.

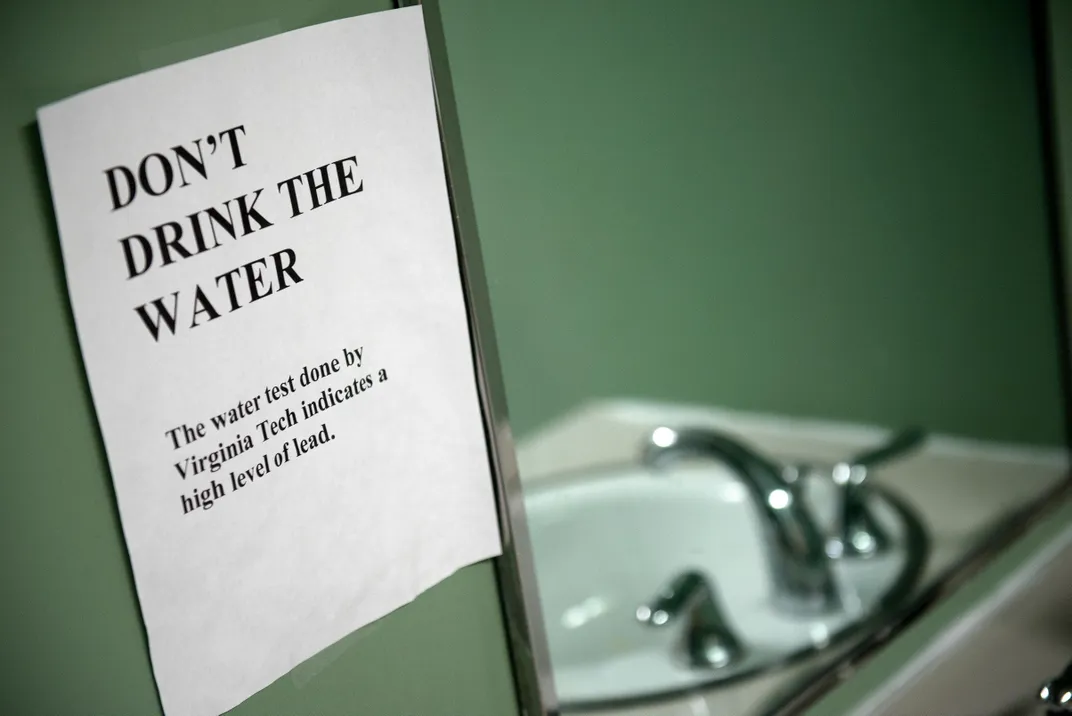

Alarmed, Walters telephoned Edwards, after getting his number from a scientist at the EPA. Edwards, well known for exposing a water scandal in Washington, D.C. a decade earlier, instantly agreed to help. “In the aftermath of Washington, D.C., I knew that something like Flint was inevitable,” he recalls. He visited Flint numerous times and supplied Walters with hundreds of water-testing kits. Flint residents used those to collect tap water samples and sent them to VT for analysis.

The resulting evidence, which they announced at a press conference in September 2015, showed spiking lead levels, concentrated in the poorest neighborhoods. “If they didn’t believe us from this, no one was ever going to believe us,” Walters recalls.

Indeed, Brad Wurfel, a spokesman for the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, responded at the time that “Flint drinking water meets state and federal safe drinking water standards.” He also tried to discredit Edwards’ lab. “This group specializes in looking for high lead problems,” he said then. “They pull that rabbit out of that hat everywhere they go.”

Officials could no longer explain away the problem when Hanna-Attisha, the pediatrician, released new data showing that the number of children in Flint with elevated blood lead levels had nearly doubled since 2014. The hardest-hit were concentrated in areas where Walters and Edwards had documented high lead levels in the drinking water.

The crisis sparked such an outcry that celebrities such as Cher, Big Sean and Matt Damon donated money or water to help city residents—and called for Governor Snyder to resign. That didn’t happen, but Wurfel and several other officials were forced out, and so far nine state and city employees have been indicted for covering up or failing to address the problem.

Edwards says the official stonewalling fits a pattern of bureaucracies closing ranks. “At some point it crosses the line from what might have been a simple, relatively innocent but stupid mistake, into ignoring one warning sign after another. They were going to work overtime to cover this up. ‘Force us to do our job’—that was their attitude.”

He speaks from experience. Starting in 2003, he led testing efforts in Washington that showed that chloramine, a disinfectant added to water, was corrosive and linked to rising lead levels. But while he was working to document the phenomenon, the D.C. Water and Sewer Authority refused to issue lead warnings. Then that agency and the EPA terminated testing contracts with him. He continued anyway, spending his own money (including a second mortgage on his house and a $500,000 MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant) to pay for testing and research. Eventually, he was proven correct. “Your whole worldview is overturned,” he says of his disillusionment with public health agencies that cut corners and obstruct research.

The city of Flint is working—slowly—to resolve the crisis. The state has ponied up $240 million for a variety of lead remediation and public health programs, including a $55 million project to replace thousands of lead service lines. Residents are still advised to use water filters, and many are sticking with bottled water. Lead levels have fallen, but remain high in some homes. Lead poisoning can have lifelong effects. Gavin Walters’ growth remains stunted, his mother says. Thousands of children are affected, says Hanna-Attisha.

Erin Brockovich, the consumer advocate, credits Walters for sticking up for her family’s health. “I’ve been doing this for 20 years, and in every community there is a LeeAnne, and they’re pissed,” says Brockovich, who helped show that drinking water in Hinkley, California, was contaminated with chemicals released by Pacific Gas and Electric (as depicted in the film about her starring Julia Roberts). “These women are good at going to schools, drumming up attention, getting their neighbors involved. They’re told, ‘You’re not a doctor or a scientist or a lawyer, you have no business getting involved in this.’ But they will not take no for an answer.”

In October 2015, Walters began splitting her time between Flint and Virginia because her husband was transferred to Norfolk. This past April she co-founded the Community Development Organization of Flint, or C Do, to provide support for citizens with lead-related problems.

Aging water systems are now a national concern. A 2016 study by the Natural Resources Defense Council found that 5,300 U.S. water systems were in violation of various federal lead standards, and that the EPA and state agencies were following up on only a fraction of those cases.

People in many U.S. cities are collecting their own water for testing and turning to Edwards and his lab. On the day I visited, there was a table with dozens of white plastic bottles containing tap water collected in Philadelphia and New Orleans, ready to be analyzed. “There are other communities out there who are going through the same sort of thing, and don’t know about it,” Edwards says. “The miracle of Flint was, they got caught.”

Related Reads

Lead Wars: The Politics of Science and the Fate of America's Children