Why Anaerobic Digestion Is Becoming the Next Big Renewable Energy Source

A food-to-electricity plant in England is just one in a string of local efforts to make waste less wasteful

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/ac/fdac3a24-de60-40b5-ac83-f5ab89b6bb80/ha5a5927-dairy-digester-lr.jpg)

When Resourceful Earth Limited announced it would be building a facility to convert 35,000 tons of the local food waste to power each year—enough to provide 80 percent of the energy to the nearby town of Keynsham, U.K—the company became the latest to employ anaerobic digestion to reduce waste, generate energy and cut down on carbon emissions. It’s localism taken to its conclusion, not just what a community buys, but what it gets rid of, too.

“That’s our ideal plan, to make … a system where we’re actually a closed loop,” says Jo Downes, brand manager for Resourceful Earth. “It’s all self contained. Food waste is produced by a community, it’s converted to electricity, and it goes back to that community again. It’s self-sustaining.”

Anaerobic digestion, as a way of converting biomass to energy, has been practiced for hundreds of years, but the effort in Keynsham is one indicator of the technology’s maturation. As focus around the world has turned to renewable energy, anaerobic digestion has started to become an economically viable energy source that capitalizes on humans at our most wasteful—and most creative. Local municipalities, including wastewater facilities, as well as private companies and even the Department of Energy are fine-tuning the tech to make it more efficient and practical.

“Anaerobic digestion is fascinating because it’s a relatively easy, natural way of turning a broad variety of complex waste into a simple fuel gas,” says David Babson, a technology manager at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Bioenergy Technologies Office. “Closing waste loops and recovering energy from waste presents a profound opportunity to simultaneously improve waste management and address climate change.”

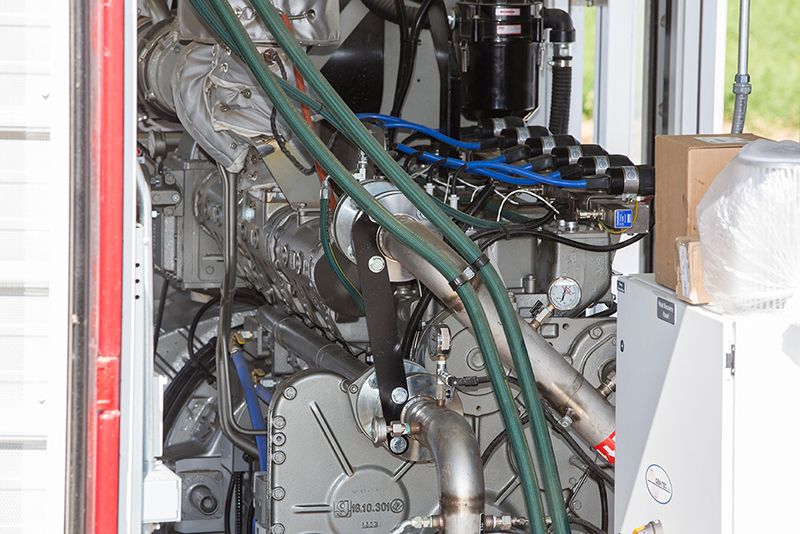

The technology itself is rather simple. Enclose a mixture of moist, organic material like kitchen waste, or waste from humans or farms or food processing facilities, in an oxygen-free container with naturally occurring anaerobic bacteria. The waste breaks down through four different consecutive processes, ultimately releasing carbon dioxide, water, methane, and a dark slurry of organic material and nutrients called digestate. The methane is siphoned off, and refined for use as a fuel, or burned to power turbines.

Modern anaerobic digestion got its start in the wastewater industry. Municipalities, like the East Bay Municipal Utility District in Northern California, realized that in the course of treating wastewater from households, farms and food processing facilities, they could add a step to produce some of their own energy. For EBMUD, the last 15 years have been a journey in search of greater efficiency and energy production capacity. Waste treatment is an energy intensive process, and with the installation of 11 anaerobic digestion units and three turbines, EBMUD now produces 135 percent of its energy needs, leaving additional power that can then be sold, says Jackie Zipkin, manager of wastewater engineering there.

“One of the things that’s exciting about the type of renewable energy that we produce is that it’s 24/7, and when you look at things like solar and wind, they don’t have that baseload capability,” says Zipkin. “I think there’s more and more interest nationally in renewable energy, and particularly from biogas.”

Meanwhile, in addition to working with hotels and restaurants to develop a food waste collection program, the Sacramento Municipal Utility District has expanded in its own way, working with dairy farms to provide on-site digesters for manure and waste from lagoons. Dairies are the biggest methane emitter in California, says Valentino Tiangco, a biomass program manager at SMUD. As a greenhouse gas, methane is particularly potent, though not long lived; little can be done about ruminant methane belches, but diverting manure to anaerobic digesters can reduce overall methane output, and the utility district is helping Sacramento County dairies get grants to offset the high initial cost of the digesters.

As EBMUD, SMUD and other municipalities realized they could innovate in this field, they began experimenting with different techniques, organic mixtures and processes, and paved the way for other more complicated projects. The cycle of consumption and waste that drives communities could be hacked to close a lot of the holes where valuable waste gets, well, wasted. It’s sort of a “use the whole animal” premise, but with organic waste.

Resourceful Earth is also closing several loops, using surplus heat from the process to dry wood chips that are used in biomass boilers, and sending nutrient-rich digestate to farms for use as fertilizer. If the company can provide 80 percent of the town’s energy, as it claims, it could act as a model for local scale anaerobic digestion, where food, energy and fertilizer all create an efficient, closed loop.

The U.S. Department of Energy is working to optimize distribution and supply chains, but more importantly, says Babson, to refine the chemical process that converts the waste. If they can stop the process short, after it is broken down into alcohols but before it transitions into methane and carbon dioxide, the products could be refined into jet fuel, gasoline and other high-value products—all of which would be considered renewable, since the carbon released was absorbed from the atmosphere by the plants that became the food, that became the waste, that became the gas.