Why Are We Always Searching For “A Quiet Place?”

Perhaps the real monster is not noise, but instead our own intolerance of unwanted sounds

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/60/cb609078-700d-4c22-83ef-3f8bac3b03cb/file-20180418-163962-ryo3bg.jpg)

The new film A Quiet Place is an edge-of-your-seat tale about a family struggling to avoid being heard by monsters with hypersensitive ears. Conditioned by fear, they know the slightest noise will provoke a violent response – and almost certain death.

Audiences have come out in droves to dip their toes into its quiet terror, and they’re loving it: It’s raked in over US$100 million at the box office and has a 95 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

Like fairy tales and fables that dramatize cultural phobias or anxieties, the movie may be resonating with audiences because something about it rings true. For hundreds of years, Western culture has been at war with noise.

Yet the history of this quest for quietness, which I’ve explored by digging through archives, reveals something of a paradox: The more time and money people spend trying to keep unwanted sound out, the more sensitive to it they become.

Be quiet – I’m thinking!

As long as people have lived in close quarters, they’ve been complaining about the noises other people make and yearning for quiet.

In the 1660s, the French philosopher Blaise Pascal speculated, “the sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room.” Pascal surely knew it was harder than it sounds.

But in modern times, the problem seems to have gotten exponentially worse. During the Industrial Revolution, people swarmed to cities roaring with factory furnaces and shrieking with train whistles. German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer called the cacophony “torture for intellectual people,” arguing that thinkers needed quietness in order to do good work. Only stupid people, he thought, could tolerate noise.

Charles Dickens described feeling “harassed, worried, wearied, driven nearly mad, by street musicians” in London. In 1856, The Times echoed his annoyance with the “noisy, dizzy, scatterbrain atmosphere” and called on Parliament to legislate “a little quiet.”

It seems the more people started to complain about noise, the more sensitive to it they became. Take the Scottish polemicist Thomas Carlyle. In 1831, he moved to London.

“I have been more annoyed with noises,” he wrote, “which get free access through my open windows.”

He became so triggered by noisy peddlers that he spent a fortune soundproofing the study in his Chelsea Row house. It didn’t work. His hypersensitive ears perceived the slightest sound as torture, and he was forced to retreat to the countryside.

The war on noise

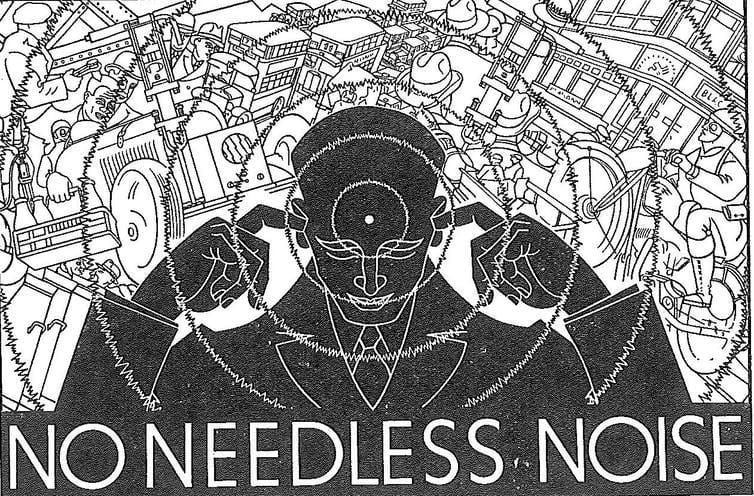

By the 20th century, governments all over the world were engaged in an endless war on noisy people and things. After successfully silencing the tug boats whose tooting tormented her on the porch of her Riverside Avenue mansion, Mrs. Julia Barnett Rice, the wife of venture capitalist Isaac Rice, founded the Society for the Suppression of Unnecessary Noise in New York in order to combat what she called “one of the greatest banes of city life.”

Counting as members over 40 governors, and with Mark Twain as their spokesman, the group used its political clout to get “quiet zones” established around hospitals and schools. Violating a quiet zone was punishable by fine, imprisonment or both.

But focusing on noise only made her more sensitive to it. Like Carlyle, Rice turned to architects and built a quiet place deep under the ground, where her husband, Isaac, could work out his chess gambits in peace.

Inspired by Rice, anti-noise organizations sprang up around the globe. After World War I, with ears across Europe still ringing from explosions, the transnational culture war against noise really took off.

Cities all over the world targeted noisy technologies, like the Klaxon automobile horn, which Paris, London and Chicago banned by ordinance in the 1920s. In the 1930s, New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia launched a “noiseless nights” campaign aided by sensitive noise-measuring devices stationed throughout the city. New York passed dozens of laws over the next several decades to muzzle the worst offenders, and cities throughout the world followed suit. By the 1970s, governments were treating noise as environmental pollution to be regulated like any industrial byproduct.

Planes were forced to fly higher and slower around populated areas, while factories were required to mitigate the noise they produced. In New York, the Department of Environmental Protection – aided by a van filled with sound-measuring devices and the words “noise makes you nervous & nasty” on the side – went after noisemakers as part of “Operation Soundtrap.”

After Mayor Michael Bloomberg instituted new noise codes in 2007 to ensure “well-deserved peace and quiet,” the city installed hypersensitive listening devices to monitor the soundscape and citizens were encouraged to call 311 to report violations.

Consuming quietness

Yet legislating against noisemakers rarely satisfied our growing desire for quietness, so products and technologies emerged to meet the demand of increasingly sensitive consumers. In the early 20th century, sound-muffling curtains, softer floor materials, room dividers and ventilators kept the noise from the outside from coming in, while preventing sounds from bothering neighbors or the police.

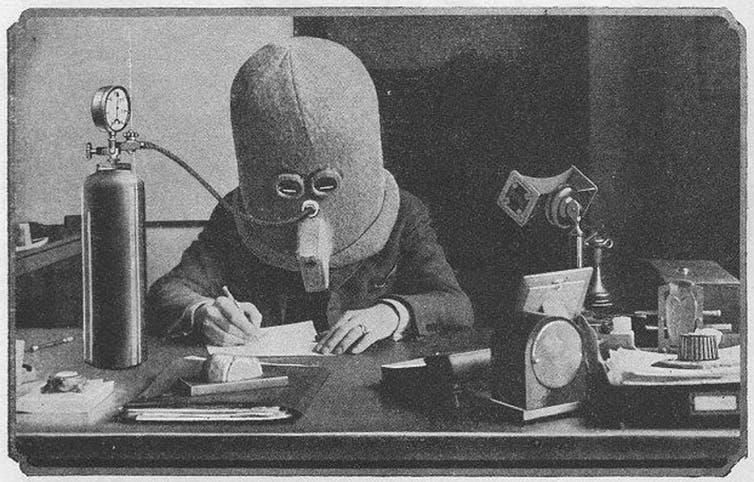

But as Carlyle, Rice and the family in A Quiet Place found out, creating a sound-free lifeworld is nearly impossible. Certainly, as Hugo Gernsback learned with his 1925 invention the Isolator – a lead helmet with viewing holes connected to a breathing apparatus – it was impractical.

No matter how thoughtful the design, unwanted sound continued to be a part of everyday life.

Unable to suppress noise, disquieted consumers started trying to mask it with wanted sound, buying gadgets like the Sleepmate white noise machine or by playing recorded sounds of nature, from breaking waves to rustling forests, on their stereos.

Today, the quietness industry is a booming international market. There are hundreds of digital apps and technologies created by psychoacoustic engineers for consumers, including noise cancellation products with adaptive algorithms that detect outside sounds and produce anti-phase sonic waves, rendering them inaudible.

Headphones like Beats by Dr. Dre promise a life “Above the Noise”; Cadillac’s “Quiet Cabin” claims it can protect people from “the silent horror film out there.”

The marketing efforts for these products aim to convince us that noise is intolerable and the only way to be happy is to shut out other people and their unwanted sounds. This same fantasy is mirrored in A Quiet Place: The only moment of relief in the whole “silent horror film” is when Evelyn and Lee are wired in together, swaying gently to their own music and silencing the world outside their earbuds.

In a Sony ad for their noise canceling headphones, the company depicts a world in which the consumer exists in a sonic bubble in an eerily empty cityscape.

Content as some may feel in their ready-made acoustic cocoons, the more people accustom themselves to life without unwanted sounds from others, the more they become like the family in A Quiet Place. To hypersensitized ears, the world becomes noisy and hostile.

Maybe more than any alien species, it’s this intolerant quietism that’s the real monster.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Matthew Jordan, Associate Professor of Media Studies, Pennsylvania State University