When Tim Crist was five years old, he walked into a Pizza Hut in Potsdam, New York, and his life changed forever. It was 1981, and a new video game was getting a lot of buzz. Crist slipped a quarter into the machine, and played Pac-Man for the very first time.

“I was terrible at the game,” he recalls. “I had no idea what I was doing with the ghosts. But it stuck with me somehow.”

As a kid, Crist doodled his own Pac-Men in art class—though they were green, to match the Pizza Hut cabinet’s broken screen—and poured tens of thousands of quarters into arcades. Later, as an adult, , he collected Pac-Man memorabilia and used his training as a software programmer to build a game called Pac-Kombat (a two-player version of Mortal Kombat, with Pac-Man characters). He even wrote a song about Pac-Man with his comedy synth-punk band, Worm Quartet. “You hear about the yellow guy?” the lyrics start. “Ooh, he eating lots of dots.”

In 2004, Crist’s fandom caught the attention of VH1. A camera crew spent two days filming, culminating in an iconic scene in which Crist drove around a mostly-empty mall parking lot—his car complete with a Pac-Man-themed steering wheel wrap and fuzzy dice—yelling “PAC-MAN!” out his open window at passers-by. The scene appeared on VH1’s Totally Obsessed, a short-lived reality show that profiled superfans. To date, Crist’s stint as a reality TV star has racked up more than 3.7 million views on YouTube, solidifying his reputation as “the Pac-Man guy” for good.

Other collectors had amassed more impressive caches of Pac-Man memorabilia than Crist’s hoard, which today includes Pac-Man plush toys, school supplies, a joke book, and even a full-sized arcade cabinet. But producer Steve Czarnecki says it was Crist’s infectious energy that caught his attention, “like a larger-than-life Weird Al Yankovic” complete with long, curly hair. At the time, Crist maintained a lighthearted religious parody blog he dubbed the Church of Pac-Man, revealing his unique and silly sense of humor. “I don’t remember if we asked him to play it up so crazy, or if he just took it upon himself to be a complete nut,” Czarnecki says, recalling the two days he spent filming with Crist, “but we had a lot of fun.” (Crist says he intentionally hammed it up.)

Though most Pac-Man fans fall short of Crist’s devotion, his story reflects both the intense fandom Pac-Man has inspired, and the franchise’s longevity. The classic arcade game—which turns 40 on May 22—made history by launching an unprecedented merchandise empire that would later fuel collections like Crist’s. But Pac-Man was innovative in other ways, too. During a time when video games’ default audience was adult men, Pac-Man successfully engaged women and children, becoming one of the first games to broaden the medium’s appeal in both the U.S. and Japan.

The Birth of Pac-Man

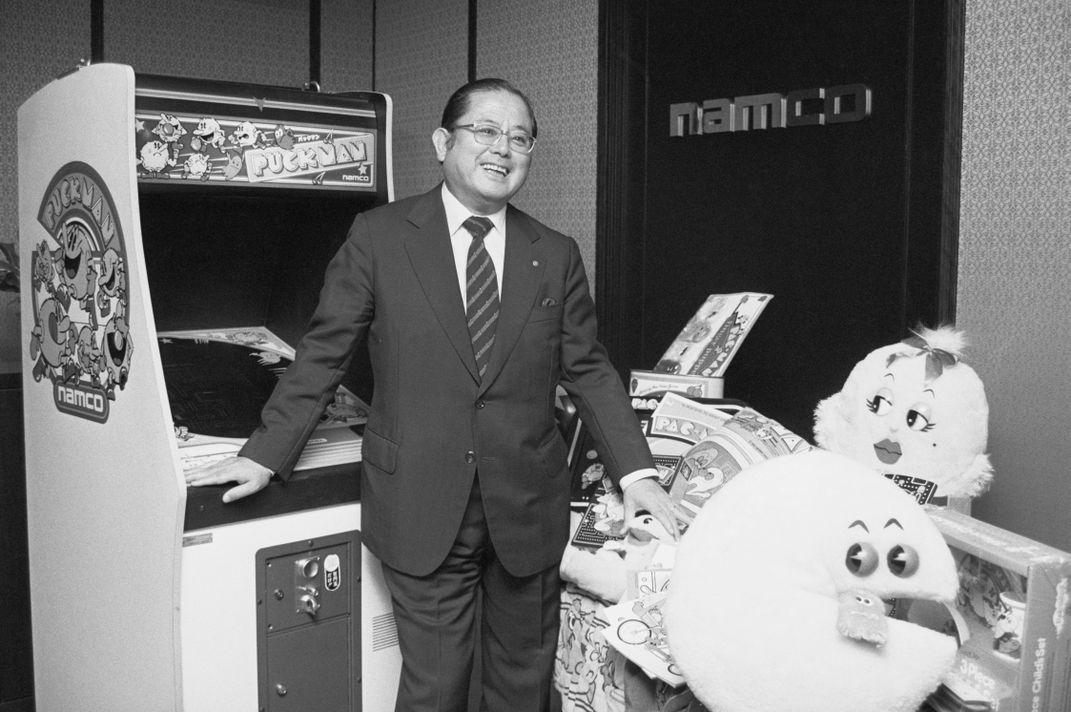

Pac-Man’s story began in Japan during the 1980s, during the “Japan as Number One” era, which was defined by a manufacturing boom and strong yen. Japan’s robust economy fueled the emergence of a new, free-wheeling business culture, and Namco—the Japanese company behind Pac-Man—was part of this new wave. “I want people who think in unusual ways, whose curiosity runs away with them, fun-loving renegades,'' founder Masaya Nakamura told the New York Times in a 1983 profile. Back then, Namco was known for running recruiting advertisements in magazines, which called for “juvenile delinquents and C students.” Nakamura was also known for personally sinking hours into testing Namco’s games—sometimes up to 23 hours per day if the company was close to launching a new product.

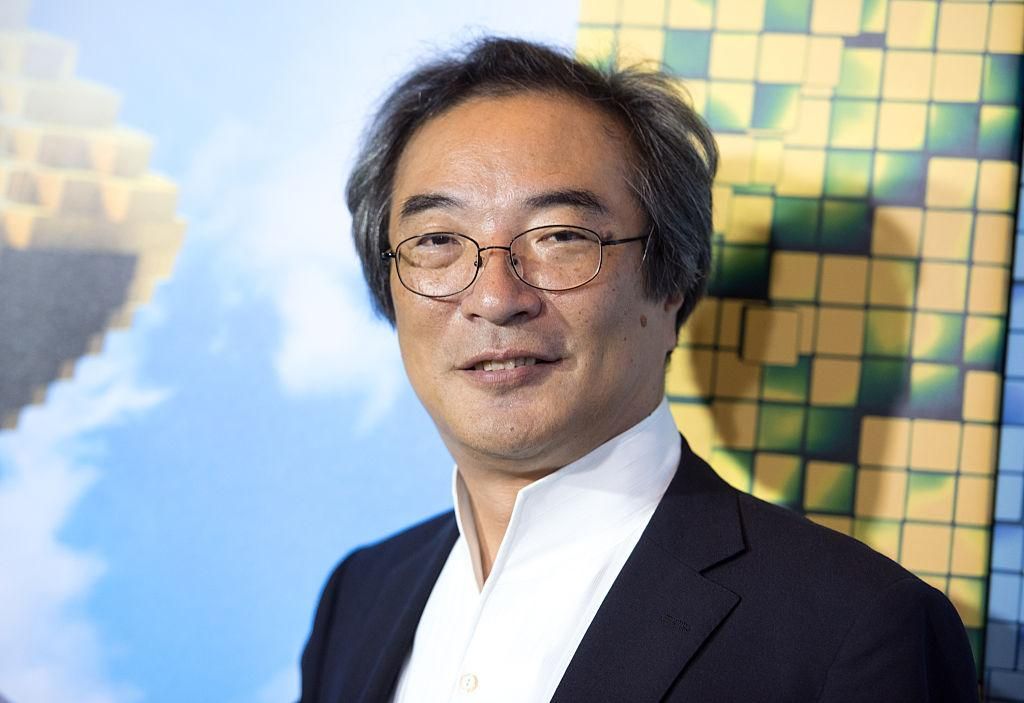

Toru Iwatani was one of the free-thinking employees who worked in Namco’s unusual environment. Tasked with designing a new cabinet game, Iwatani reflected on what existing games already offered, as well as who played them—all in hopes of creating something completely new.

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, video games were associated with male-dominated spaces in both Japan and the U.S. Arcades emerged after video games had already become a hit, says historian Carly Kocurek, a cultural historian at the Illinois Institute of Technology and author of Coin-Operated Americans. Instead, early cabinet games such as 1972’s Pong followed existing distribution routes for other coin-operated services, such as cigarette machines. As cabinet games caught on, they began popping up in bars, bowling alleys and movie theaters, as well as chains including Holiday Inn and Wal-Mart. “Anywhere where people might be waiting around,” Kocurek says. Although women have always played video games, they represented a minority of players in these public spaces.

By the time Space Invaders arrived in 1978, the coin-op industry realized that video games could be incredibly lucrative. Across the U.S., arcades began to gather popular games into concentrated spaces, but did little to welcome a more diverse audience. According to Kocurek, arcades were even less hospitable than bars. They offered an overwhelming sensory experience defined by low light, loud noises and often extreme heat that radiated from the cabinets themselves. Whether fair or not, arcades also became associated with teenage delinquency. “If a place is for teenagers, other people don't go,” Kocurek says.

Iwatani was determined to make a video game that broke with this status quo. “This perception [of arcades as dude hangouts] was similar in Japan,” Iwatani told Time in 2015. “I wanted to change that by introducing game machines in which cute characters appeared with simpler controls that would not be intimidating to female customers and couples to try out.”

As he reflected on this gap in the video game market, Iwatani drew inspiration from media he enjoyed. “He actually grew up on a lot of Disney cartoons,” says Shannon Symonds, a historian and curator at The Strong National Museum of Play. According to Symonds, Iwatani also loved shōjo manga and anime—animated stories written primarily for young women. “It was never his intention to create something [with] a violent feel,” Symonds says. “He wanted to create something that people would feel comfortable playing as a family, or out on a date.” Iwatani thought young women enjoyed eating, and that perhaps the gameplay could involve food in some way. “I’m not exactly sure how I feel about that,” Symonds says, laughing. “But I feel like the intentions behind it were in the right place.”

Kocurek agrees, pointing out that early video game designers rarely catered to a specific audience. “It's not that people were making bad games, or they were not being thoughtful,” Kocurek says. But Iwatani’s decision to reflect on who might play his games nudged the industry in a new direction. “That’s a really important development in the medium—we start thinking about games as having audiences, and that you would have different kinds of games for different people or different kinds of players.”

At some point during this period of ideation, Iwatani wandered to a restaurant during his lunch break. Hungry that day, he ordered an entire pizza. While eating a slice, he was struck by sudden inspiration: The pie’s wedge-shaped void resembled a gaping, hungry mouth in a round creature. The shape reminded him of a rounded version of kuchi, the Japanese character for “mouth.” Having settled on a character design, Iwatani derived its name from “paku paku,” a Japanese onomatopoeia for eating—the same sound that would inspire the game’s signature, soothing wakka-wakka sound as Pac-Man gobbles dots and fruit. (In Japan, the game debuted as Puck-Man, but was tweaked for an American audience to dissuade vandals from tweaking the “P” into an “F.”) “While I was designing this game, someone suggested we add eyes,” Iwatani later said. “But we eventually discarded that idea because once we added eyes, we would want to add glasses and maybe a moustache. There would just be no end to it.” Just like that, Pac-Man had arrived.

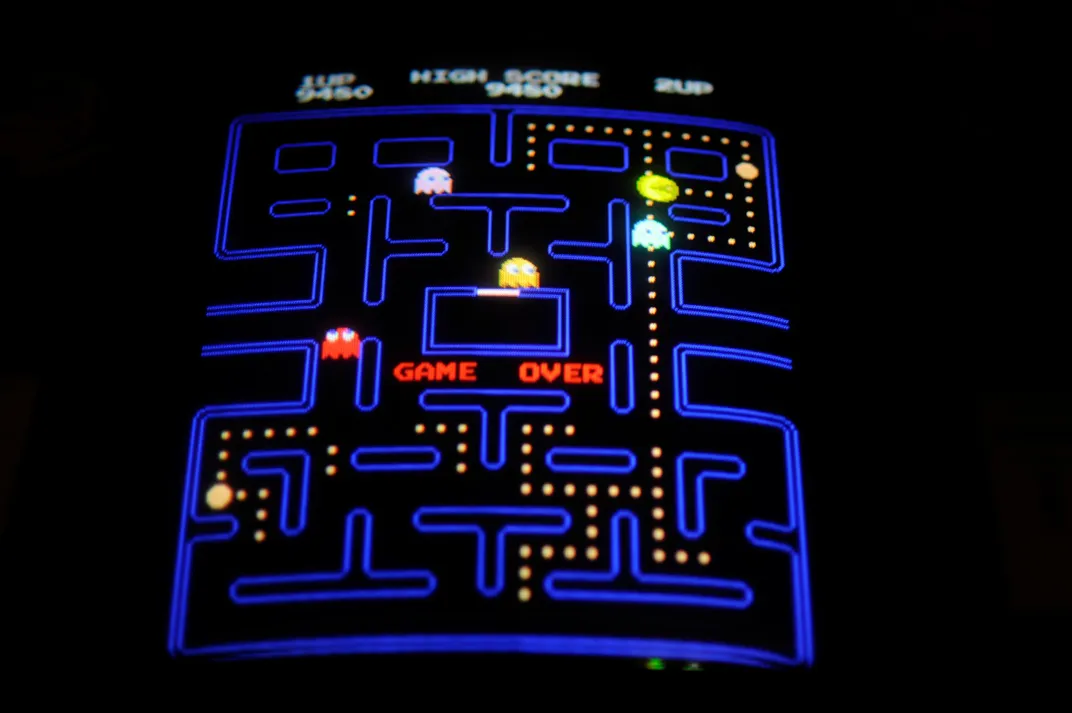

With a main character in mind, Iwatani completed the design with a team of nine Namco employees, making other innovative choices along the way. Instead of replicating popular shooters, he created Pac-Man’s unique maze design, which required joystick speed and agility to rack up points and avoid enemies. To further reassure players of the game’s nonviolence, Pac-Man’s ons-creen losses come with cartoonish sound effects, and even the ghosts Pac-Man chomps reappear moments later. As for the enemies—Technicolor ghosts named Blinky, Pinky, Inky and Clyde—Iwatani modeled them after Japan’s Obake no Q-Taro (“Little Ghost Q-Taro”), a mischievous, Casper-like spirit who starred in anime and manga. The result was a game that was downright kawaii, says Symonds—a Japanese term for things that are extremely cute.

Pac-Man Fans

By building these departures from the norm into Pac-Man, Iwatani posed a bold question: Could a different type of game attract a new audience?

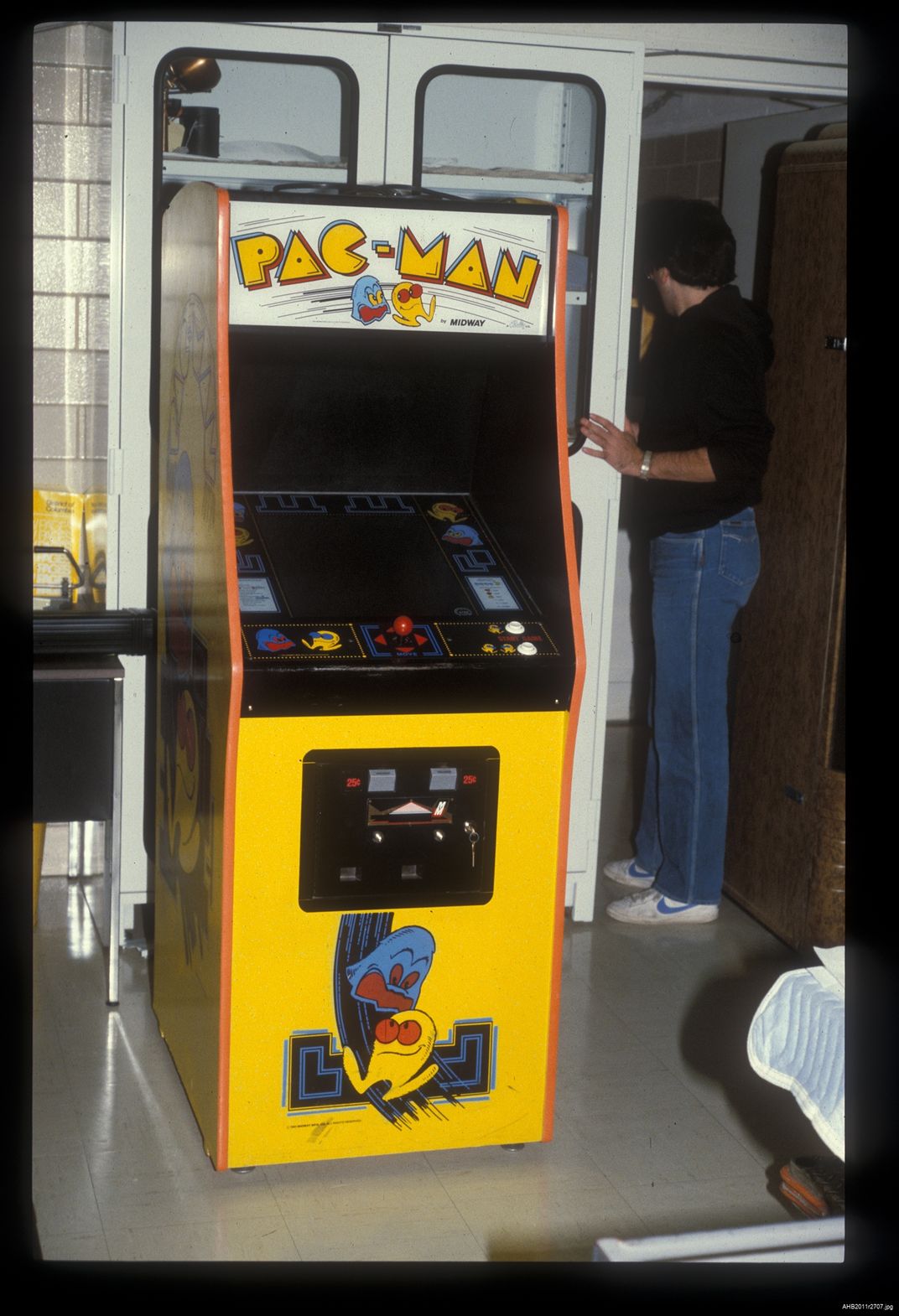

The answer turned out to be a resounding yes. Namco released the game in Japan in 1980, and it arrived in North America shortly after, thanks to a licensing and distribution deal with Bally Midway, an American company that manufactured pinball machines and arcade games. Within a year and a half, Namco sold 350,000 Pac-Man cabinets—the equivalent of $2.4 billion in sales today. By 1982, Americans were pouring an estimated $8 million, quarter by quarter, into Pac-Man each week. In Washington D.C., arcade games brought in so much revenue that the City Council proposed doubling taxes on coin-op games from five to 10 percent, according to a Washington Post article published in 1982. As the 1990s drew to a close, Pac-Man sales surpassed $2.5 billion, making it the highest grossing video game in history.

By then, some within the video game industry were paying closer attention to the intricacies of audience research. At Atari, Carol Kantor and Coette Weil pioneered market research techniques that included studying female arcade gamers. Like Pac-Man, Centipede, a coin-op game created by programmer Dona Bailey, drew an audience of male and female gamers. Though hard numbers about in-house diversity and audience demographics remain elusive, it was clear that women were gaining traction both within the industry and as consumers.

At the same time, Pac-Man’s overwhelming success spawned and was reinforced by a vast empire of merchandise—some licensed, some not, all at a scale that was completely unprecedented. “There was nothing like that up until then in video game history,” Symonds says. In 1982, there was even a song by Buckner and Garcia, “Pac-Man Fever,” which went on to become a Top 10 radio hit. These products saturated every corner of the consumer market, bringing even shoppers who had no interest in video games into contact with Pac-Man. Video games’ long association with smoky bars populated by men seemed over at last. "People say, 'Who buys Pac-Man?' It's one of the few games where the answer is, 'Everyone,"' said Scott Rubin, general manager of Namco America, on Pac-Man’s 25th anniversary.

At the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, curator Hal Wallace manages the Electricity Collections, which include the museum’s Pac-Man cabinet and related merchandise. In 1984, Bally Midway offered 200 pieces of Pac-Man merchandise—everything from leg warmers to ceramic wind chimes, gold jewelry to cereal—to the museum. The original typewritten list of these items is part of the collection, along with 38 items hand selected by the curators, including a Pac-Man-themed bathrobe, jigsaw puzzle and AM radio headset.

Around 2010, Wallace was tasked with inventorying the museum’s Pac-Man collection and made a surprising discovery. Not only had the original curators acquired Pac-Man-themed foods, including canned pasta, but the items had started to spoil. “One of the cans was swelling up and had actually breached,” Wallace recalls. “We removed the labels from the remainder of the canned goods, but we had to dispose of the remaining cans.”

Wallace says that the museum’s unusual decision to collect food items occurred during a poignant moment for the National Museum of American History. Roger Kennedy, then the museum’s director, was in the process of reorganizing the museum into three floors, each telling a century’s worth of history. For young historians like Wallace, this shake-up felt like a changing of the guard that occurred alongside academia’s adoption of a new theory called social constructivism, which placed artifacts in a broader cultural and social context. “By looking at Pac-Man and this ephemera, what does that tell us about the society that it's embedded in?” Wallace asks. “And from a business standpoint, you know, what's it tell us about the economics of the time period that people are buying these things?” In the mid-1980s, this thinking radically reframed what museums collected, and why—yet no one was sure whether the shift would be permanent. Perhaps the museum collected canned pasta because no one knew how long the moment would last.

But Pac-Man, and video games in general, proved to be more than a fad, and these questions continue to fascinate Wallace, Symonds, Kocurek and other historians. When The Strong first began collecting and displaying video games alongside its usual exhibits of toys, dolls and games, Symonds says that some visitors expressed shock and anger. Within scarcely a decade, public opinion has shifted considerably. “I think that, honestly, is amazing, just from a historical perspective,” Symonds says. “It shows how video games have integrated themselves into our culture in general, but especially into our culture of play.”

Pac-Man Meet Ms. Pac-Man

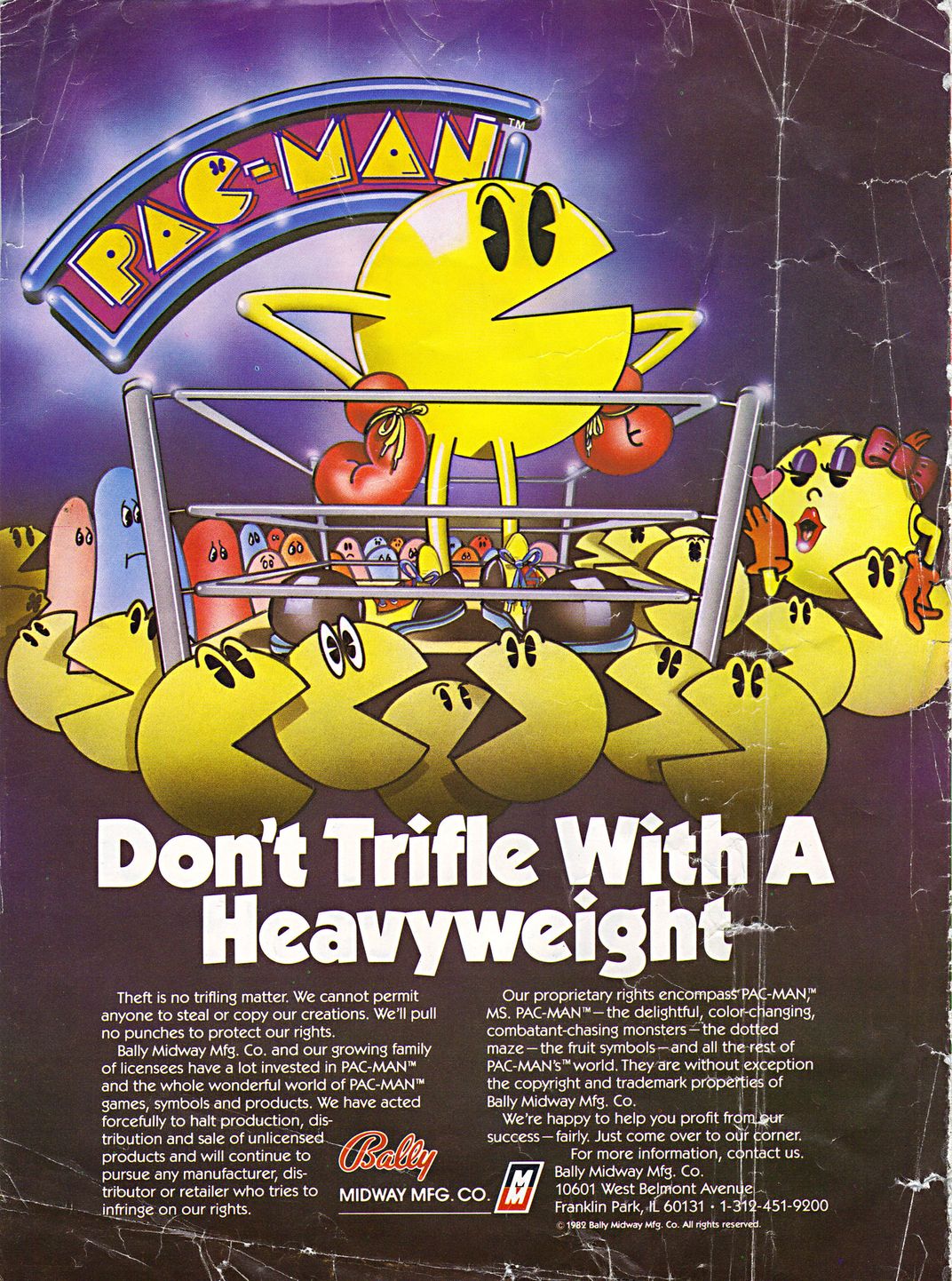

One artifact in the museum’s collection provides some insight into the messy reality behind the big business of Pac-Man. A 1982 Bally Midway advertisement shows Pac-Man in the center of a boxing ring, surrounded by Pac-People who gaze up at him. “Don’t Trifle With a Heavyweight,” the headline warns. The text below reveals that Bally Midway aggressively pursued companies that attempted to sell unlicensed Pac-Man merchandise.

Despite the ad’s firm, clear argument, the legal complexities surrounding Pac-Man were considerably more complicated. “The early intellectual property stuff around video games is really messy,” says Kocurek. Arcades and other companies that hosted cabinets would often refurbish them, swapping out the games and marquees for new games as they became available, aided by products called conversion kits. Alongside Bally Midway’s officially licensed Pac-Man kits, a murky wave of competitors swept in. A group of MIT dropouts who formed a company called General Computer Corporation (GCC), for instance, developed Crazy Otto, a game with a leggy Pac-Man knock-off.

Freshly humbled by a legal scuffle with Atari, GCC approached Bally Midway in an attempt to either sell the game or obtain the company’s blessing. After a successful test in Chicago, Bally Midway purchased Crazy Otto in October 1981, offering GCC royalties for each kit sold. “The fact [GCC founders] Doug [Macrae] and Kevin [Curran] knew that there was only one way they could sell this thing, and how they convinced Midway to do it, is just one of the great sell jobs,” recalled former GCC engineer Mike Horowitz in a Fast Company interview. “They were like 21 years old.”

With Crazy Otto performing well, Bally Midway continued its relationship with GCC, tasking the young game developers with a new challenge: Could they come up with a sequel to the bestselling game? The GCC team spent two weeks batting ideas around, and circled back to a cut scene they had created for Crazy Otto. In it, their pseudo-Pac-Man encounters a female creature. Hearts bloom over their heads, and by the end of the game, a stork delivers their baby. It felt like a rich storyline to explore, and they agreed to spin off a game about Pac-Man’s female counterpart. Initially, GCC considered Miss Pac-Man, or Pac-Woman, but both felt clunky. Eventually, they settled on Ms. Pac-Man. “The women’s movement was kind of big then–Ms. magazine–so Ms. was the new thing. I married in ’81, and my wife didn’t take my last name,” Horowitz told Fast Company.

Although the sequel originated in the U.S., Namco was aware of its development. The conversion kit system meant that each copy of Ms. Pac-Man needed to modify an existing Pac-Man game, fueling further sales of the original. Ms. Pac-Man debuted in February 1982, to “rave reviews,” generating 117,000 orders and roughly $10 million in royalties for GCC.

Within a few years, the golden age of video games came to a crashing halt. In 1983, Atari, a video game behemoth that controlled the majority of the market, missed its sales goals so monumentally that the value of Time Warner stock (its parent company) plummeted. The event, sometimes called the Atari Shock, led to an industry-wide recession. Part of the problem was Atari’s expensive decision to license E.T. for a game, but in a strange twist, Kocurek also says Ms. Pac-Man contributed to the problem. “They sunk a bunch of money into licensing Ms. Pac-Man, and then they made a terrible version of it,” Kocurek says. “By all accounts, it was really buggy.” Convinced it was going to be a hit so compelling that customers would rush to buy new gaming systems to play it, the number of copies Atari produced of its Ms. Pac-Man game exceeded the total number of Atari 2600 consoles in existence.

The Game’s Enduring Legacy

Still, Pac-Man continued to entertain new generations of casual and serious gamers alike, its simple design adapting to a wide variety of gaming systems as they emerged. Despite fluctuations within the industry, video games have earned hard-won acceptance as a legitimate art form. Today, the video games industry remains troubled by continuing problems with on-screen representation and harassment that occurs within studios and among fans. But as indie games increasingly bring much-needed diversity to the market, some predict that the industry’s future will depend on creating space for women, people of color, LGBTQ gamers and people with disabilities within the gaming community.

Meanwhile, new editions of Pac-Man continue to emerge all the time. On May 8, Google brought back its popular playable Pac-Man Doodle, urging people to stay inside and play while quarantining. In an odd coincidence, Czarnecki’s children showed him a video in which Pac-Man dons PPE and chases a frightening coronavirus cell through an animated maze, just moments before he received Smithsonian’s request for an interview.

Although Crist admits that he was upset about the way the show portrayed him when the Totally Obsessed episode first aired, he ultimately has no regrets—and still loves Pac-Man, to this day. “I had a blast doing that,” says Crist, whose sunny energy is far less manic offscreen. As the Totally Obsessed clip continues to resurface online, he gets waves of messages from people who track him down. “I’ll start getting random messages saying ‘Pac-Man!’ on Facebook,” Crist says. “I’ll be like, ‘Oh, okay, it’s out there again.’”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9d/61/9d6137c9-0618-4058-b0af-54379bdaa1ca/pac-man_closeup_on_screen-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/c8/54c87eac-5582-4407-a28b-3add2a5c4f3b/pac-man_closeup_on_screen-header.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michelle.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michelle.png)