Will Buildings of the Future Be Cloaked In Algae?

Built by a London architecture firm, a new gazebo has a living “skin” that produces oxygen and absorbs considerable amounts of carbon dioxide

In the future, green buildings may actually be green. A gazebo, unveiled this month at the Expo 2015 world’s fair in Milan, demonstrates how algae-filled plastic could serve as a living “skin” for buildings.

“This technology is really quite exciting for us because this is the first time we’ve got it to this scale,” says Marco Poletto, co-founder of ecoLogicStudio, the London architecture and urban design firm that created the 430-square-foot gazebo. EcoLogicStudio calls the project the Urban Algae Folly, playing with the traditional meaning of “folly” as an extravagant garden structure.

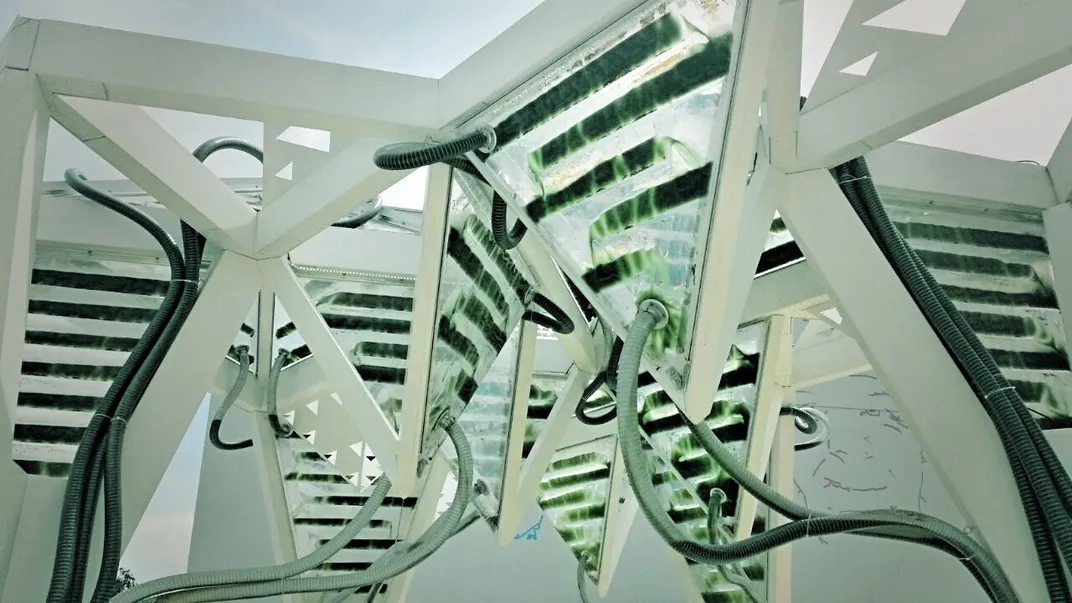

The gazebo is made of ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE), a transparent plastic building material most famously used in the Water Cube aquatics center built for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. The ETFE’s hollow interior is filled with water and spirulina, a type of algae often used as a dietary supplement. The growth of the algae will depend on sunlight and temperature, as well as on input from digital sensors that detect the presence of people and change the algae flows to create different patterns. The more sun, the more the algae will grow and darken the gazebo, providing shade for the people beneath.

A portion of the algae will be harvested every week or two to use as food; in the future, similar structures could contain different types of algae to be used as biofuels. Algae are also highly efficient at absorbing carbon dioxide and producing oxygen—though trees get all the love, algae and other marine plants make 70 percent of the world’s oxygen. The folly produces about 4.4 pounds of oxygen per day, Poletto says, enough oxygen for three adults in that time. And the structure can suck about 8.8 pounds of carbon dioxide from the air per day, he adds. A single tree absorbs only about .132 pounds each day, or about 48 pounds of carbon dioxide in a whole year.

The gazebo is part of the Future Food District in the Expo, an area of the fair dedicated to new food technologies. Advocates of spirulina, which is high in protein but rather bland, hope it might one day be a sustainable meat substitute. Today, spirulina is mostly used as a dietary supplement, added in powdered form to juices or shakes.

“Many see it as an urban food of the future,” Poletto says.

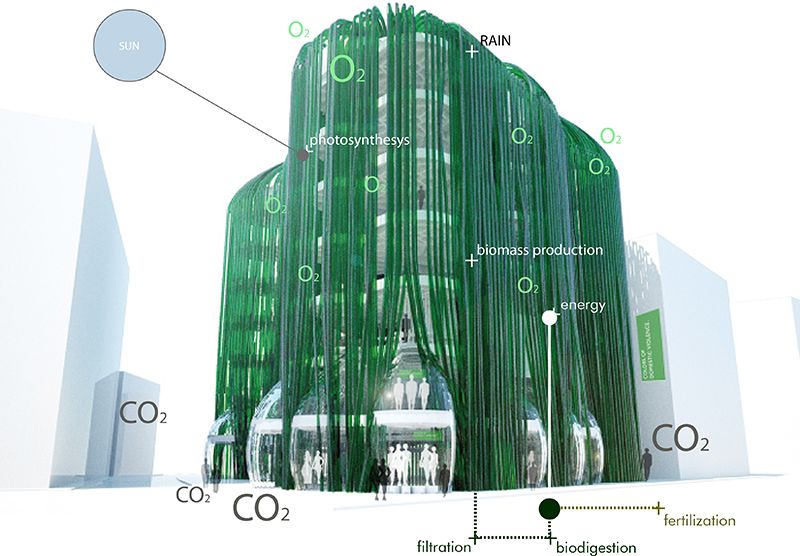

The team at ecoLogicStudio has been working on the technology for six years. They’ve consulted with a network of experts, including microbiologists, agronomists, ETFE manufacturers and computer systems engineers. Currently, the ETFE-algae structures cost about 1,200 euros (about $1,308) to build, though the price will likely drop as the technology advances. Poletto hopes to implement the technology on a much larger scale in the future. Ultimately, entire buildings could be clad in algae-filled ETFE. These green “skins” would provide shade, give off oxygen and produce food or biofuel. EcoLogicStudio has created a digital rendering of a multi-story building; Poletto says they’re in talks with various partners to make this a reality down the road.

“[The Folly] is significant because the material technology that it utilizes is fit for large and permanent architectural scenarios,” Poletto says. “This is the world first ETFE living and productive architectural skin. Now we only need investors with the vision to roll this out on a larger scale.”

Poletto and his collaborators plan to observe visitors interacting with the gazebo during the six months it’s on display at the Milan Expo. They then plan to take what they’ve learned and incorporate it into future designs.

There is some precedent for algae architecture. The Bio Intelligent Quotient house, built in 2013 in the German city of Hamburg, is covered with 129 algae-filled glass bioreactors—an exterior that cost $6.58 million. On sunny days, the algae’s growth can generate enough heat to warm the building’s floors and water. The algae is harvested once a week and taken to a nearby university to be converted into biofuel. Unfortunately the tanks make loud, rhythmic pumping noises, annoying some tenants.

Algae have also been used in a number of other recent urban innovations. French biochemist Pierre Calleja created a prototype for a “smog-eating” algae street lamp, which uses bioluminescent microalgae to light streets while absorbing carbon dioxide and producing oxygen. Last year, the Cloud Collective, a French and Dutch design group, built an algae “garden” in transparent tubes mounted to the side of a Geneva highway overpass. Rooftop spirulina farming has recently taken off in Bangkok as a form of urban food security.

Though these projects have shown promise and generated interest, the lack of larger scale implementation suggests the technology has a ways to go before “pond scum green” replaces concrete gray as the color of our cities. Poletto estimates buildings with algae façades will be common in the next five years.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)