Will Digital License Plates Drive Us Forward or Leave Us Fuming?

California-based Reviver Auto has rolled out an electronic license plate that could benefit drivers, as well as cities and states

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/79/01/7901eca5-9e0c-43ad-b356-031b112afd05/rplate.jpg)

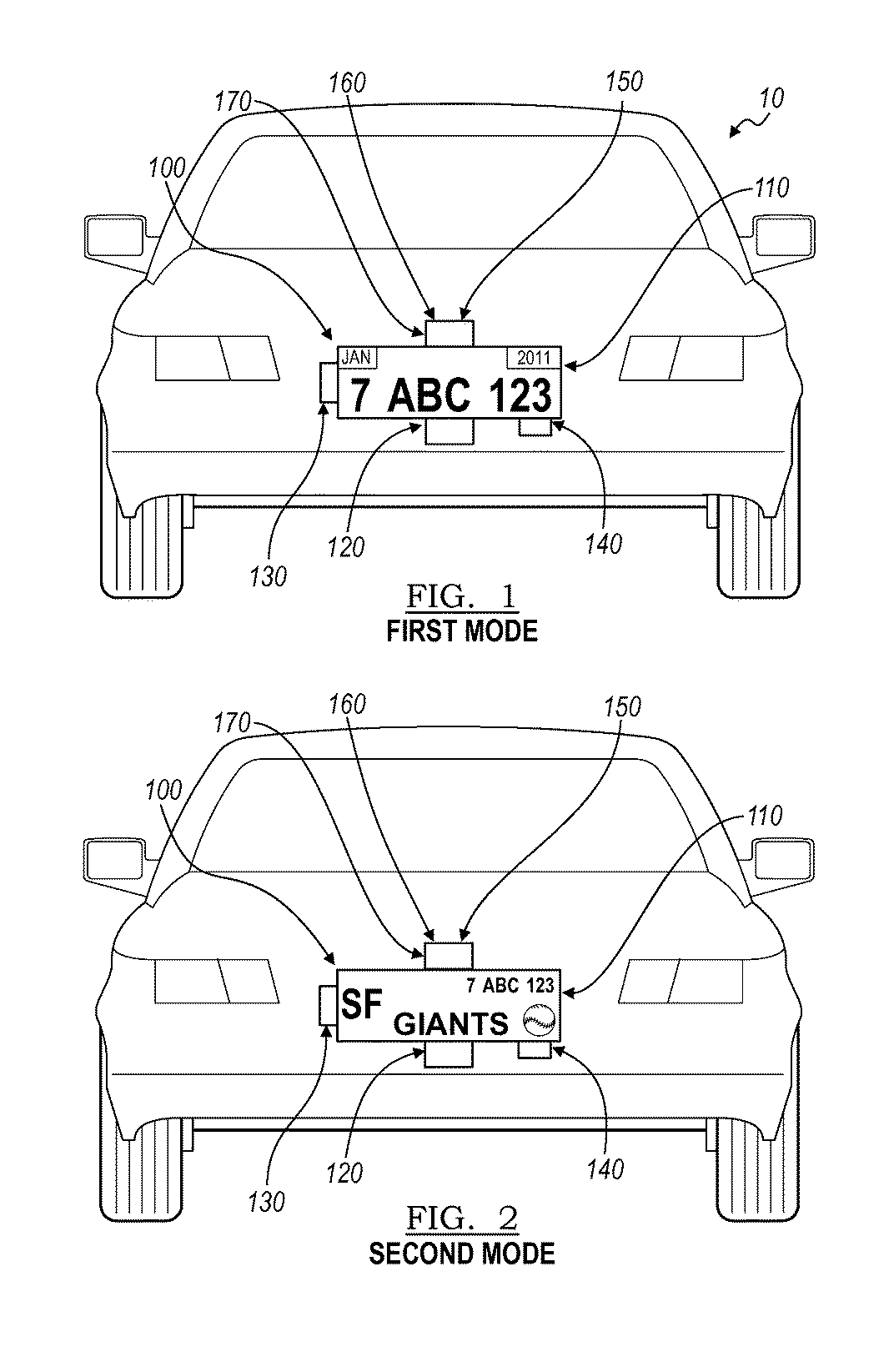

At first glance, they look like traditional license plates: alphanumeric tags with blocky letters, posted on the back of cars and trucks. But these new digital displays—already in use in California—are a far cry from their analog counterparts. Battery-powered and customizable, the reflective tablets display an identification number when the car is in motion and become a static billboard when parked, opening a range of possibilities for motorists while raising new privacy concerns.

Currently, drivers are able to customize digital plate design and update registration automatically; in the near future, those who opt to buy the devices will also be able to pay road tolls, parking meters and traffic violations automatically, track a stolen car, monitor carbon emissions and record collisions electronically—putting the convenience of technology squarely in the driver’s seat. But cybersecurity experts point to concerns about surveillance and data-mining, and it’s not hard to imagine insurers or advertisers exploiting the GPS records of thousands of drivers. As electric vehicles become mainstream and our lives increasingly digitized, digital license plates might soon pave the way for even more connectivity—as long as we understand the implications of the intelligence that runs them.

In partnership with the Department of Motor Vehicles, California-based company Reviver Auto rolled out its patented electronic license plate, the Rplate Pro, in June of 2018. The pilot program allows up to 170,000 vehicles in California to sport digital plates, and drivers in that state looking to outfit their own cars can now purchase plates through Reviver’s e-commerce site. Dealerships and pro-shops then distribute the devices and install them for a fee (depending on the vehicle, this costs around $150). Basic plates start at $499, while extra features such as telematics—that allow dispatchers to track their fleet of vehicles—bump the price to $799. Drivers must also pay a monthly subscription of $8.99 to maintain the plates after the first year, and can only install them on the rear of their car.

Despite the hefty price tag, there are obvious incentives for consumers: digital plates eliminate the headache of paying tolls and metered parking, expedite the DMV’s onerous registration process, allow for precise GPS tracking and geo-fencing, and boast technology that might someday integrate with autonomous vehicles. “A traditional stamped metal license plate’s sole purpose is vehicle identification, while digital plates offer a platform to simplify daily life,” says Neville Boston, CEO and co-founder of Reviver, noting the plates’ vast potential for innovation. Plates also offer a range of infrastructure possibilities for cities and states. Rplates can send out amber alerts (with road closures and flash flood warnings), track mileage across state lines, improve security at borders and checkpoints, and might someday be used as an alternative mechanism by which to capture transportation revenue: since plates can track an individual vehicle’s precise mileage driven instead of gas consumed, local governments could more effectively tax road use rather than fuel consumption. “Many states face major infrastructure problems” adds Boston. “The Rplate could be part of the solution.”

On April 25, 1901, New York Governor Benjamin Odell Jr. signed into law a bill requiring owners of motor vehicles to register with the state. The bill also mandated that “the separate initials of the owner’s name be placed upon the back thereof in a conspicuous place.” Buggies, roadsters and other early automobiles sported license plates that were often not plates at all: since there were no restrictions on material, size or color, vehicle owners often painted their initials on wood, enameled iron or even directly on the car itself. Now, more than a century later, changes to these roving monikers go well beyond aesthetic.

Reviver’s Digital License Plate System technology, or DLPS, is a combination of hardware and software, including cloud-based services accessible from a mobile device. The plate’s display resembles a Kindle, except that letters and numbers are made up of monochromatic “e-ink”—tiny microcapsules which are electronically charged for grayscale color, resulting in a highly reflective display that’s visible from 180 degrees and won’t fade in the sun or rain. And the plates can hold text and images indefinitely; power is drawn from a car’s battery only when the plate’s display is modified—a crucial component for law enforcement, who need to be able to read the ID number whether the car is parked or in motion. Reviver’s patented technology also enables the plates to calculate vehicle miles traveled (VMT) per trip, day and year through GPS and an accelerometer, information which drivers can elect to upload to the cloud.

All of this instrumentation raises substantial cybersecurity concerns. Businesses will eventually be able to display advertisements on the plate targeted to specific locations made available through the system’s telematics. If a driver frequently travels to a particular supermarket or bank or gun shop, who has access to the data? How long is it stored? How vulnerable are these systems to data breaches and fraud?

Reviver assures consumers that its data is not shared with the DMV, law enforcement or other third parties unless mandated by court order, and that the system’s default setting prevents data from automatically uploading to the cloud. “Reviver uses a private, encrypted network, and the company regularly conducts audits to ensure its systems are secure,” explains Prashant Dubal, who heads product management at the company and oversaw the pilot program. In this way, the Rplate functions a bit like online banking, with a rigorous authentication process and encrypted communication.

But no digital transaction is bullet-proof, particularly when the bureaucracy of government is involved. “In the age of surveillance capitalism, there is no separating the private sector from the public sector,” says Lee Tien, senior staff attorney for internet rights at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). The San Francisco-based non-profit champions user privacy and innovation through impact litigation, policy analysis and technology development; the Rplate has implications for all three. “One thing digital license plates will facilitate is tracking,” says Tien. “With machine learning, we still have a reasonable expectation that our location should remain private.” To that end, EFF maintains a robust technical department, with coders and analysts who evaluate hardware in order to help policymakers understand emerging technology and antifraud efficiency.

Andrew Conway, deputy director of registration operations at the California Department of Motor Vehicles, takes a more holistic approach to the devices: he views the Rplate as an opportunity for government to first test digital services for the American driving public before legislature decides to put them on roads nationwide. “We are trying to give a more complete picture to policymakers,” Conway explains, “so that if they decide to adopt digital plates, we can provide data about how consumers, toll-takers, etc. interact with them.” Conway helped Boston pass legislation authorizing the DMV to test the Rplate. He notes that their team initially struggled to get more than a couple dozen digital plates on the road; over time, they were able to identify consumer interest, gauge law enforcement concerns, and respond accordingly. “I want people to understand this product’s capabilities beyond the theoretical,” Conway says. “That means testing them in the real world, with willing participants.”

Reviver is still evaluating the potential benefits of its product, and plans to make the Rplate available in all major metro areas by 2021. Improvements to features that allow drivers to customize plates, aggregate payments and pinpoint their location over time could mean sound revenue for the state, which is attractive to DMVs and other government actors. But increased adoption also means vetting appropriate government uses and restrictions on rPlate data, particularly in the context of ride sharing and autonomous vehicles. Reviver is on track to expand to six states in 2019 on the West Coast, in the Midwest and in the South, suggesting that the stamped metal ID tag—virtually unchanged since the dawn of the automobile—may soon be left by the roadside.