Will Driverless Cars Mean Less Roadkill?

Avoiding wildlife could be a tough task for these super-smart cars

:focal(2514x2607:2515x2608)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/68/5b/685b2b03-20f9-46cb-bdcd-ee8a923672d1/deer-in-road.jpg)

About 20 times a day, a driver somewhere in Sweden crashes a car into a moose. The giant deer are usually injured or killed, the cars often destroyed, and the drivers frequently hurt.

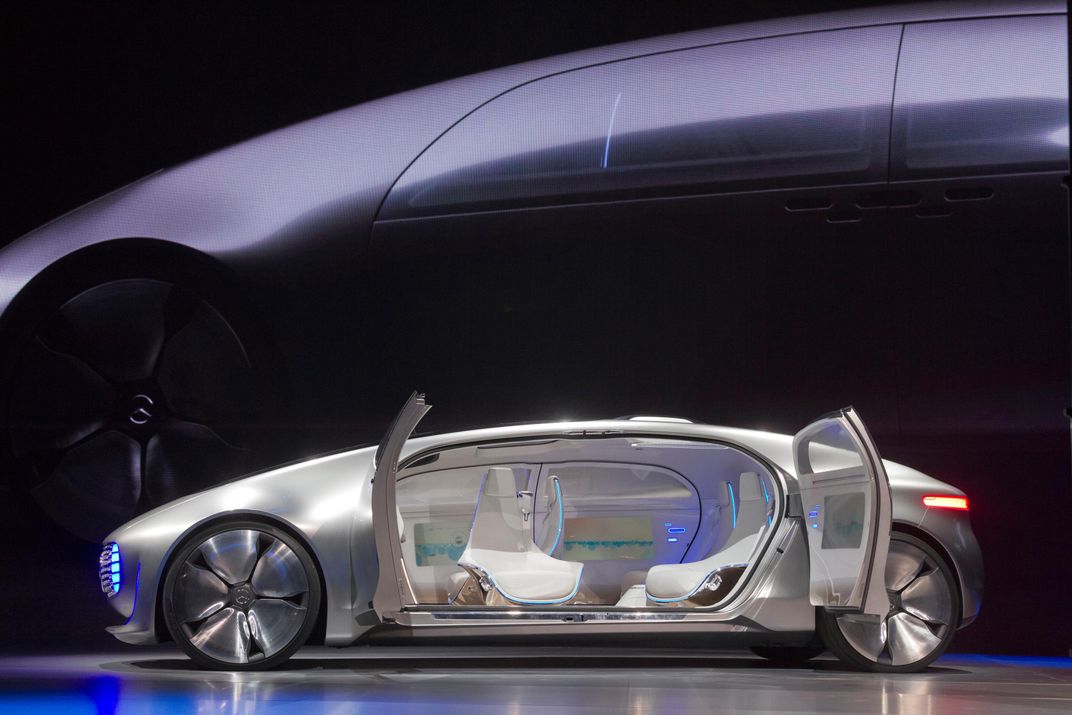

It’s an alarming statistic that engineers with the Swedish car manufacturer Volvo hope to downsize as they enter the frontier of driverless car technology. Volvo plans to have 100 autonomous vehicles in use by 2017, and more in the years following. The hope is that the cars, driven by advanced computer systems, will be safer and more efficient than error-prone human-operated vehicles.

Much of the talk is about how driverless cars could transform urban areas thick with pedestrians. But how will they stand to benefit those traveling at highway speeds on rural roads routinely crossed by moose, deer and wild pigs?

Erik Coelingh, Volvo’s senior technical leader in Göteborg, says the first step toward reducing collisions with moose is driving more slowly, which autonomous cars will do. They will also be able to both identify the animal sooner and respond to its presence faster than a human could.

Roadkill is a huge problem in the United States too, where hundreds of millions of animals die every year in collisions with vehicles. Most of these events are non-issues for the cars as their tires squash small creatures like amphibians and rodents. However, many involve animals big enough to dent metal or shatter glass. Americans crashed their vehicles into 1.25 million deer in 2014, amounting to $4 billion in damage, according to Sevag Sarkissian, media relations specialist with State Farm. The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety has reported that about 200 people are killed each year in vehicle collisions with wildlife.

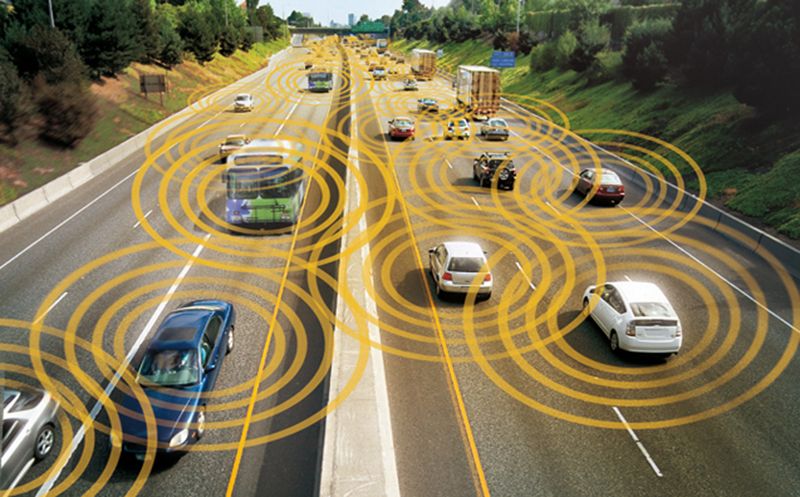

In the United States, driverless cars are already taking to the street on an experimental basis. Manufacturers promise that these marvels of the tech age will change our world. The cars will communicate with one another, allowing them to move fluidly through the streetscape while reducing traffic congestion, time spent prowling for parking and pollution. With sharper senses and faster reaction times than people, autonomous vehicles could theoretically make car-on-car collisions a thing of the past.

But outsmarting animals, engineers say, could be among the tougher tasks for these super-smart cars. The main challenge is that nature is imperfect and unpredictable, and it isn’t clear yet how the rigid calculations of computers will handle the sometimes erratic behavior of wild, as well as domesticated, animals.

“Even if we develop the perfect automated recognition and avoidance system, you still have an imperfect ecology and wildlife behavior system, so there’s maybe still too much chaos,” says Fraser Shilling, the director of the California Roadkill Observation System, a program that tracks roadkill, locates collision hotspots and aims to reduce wildlife mortality on roadways. “If your subject, the animal, is sprinting out into the road in such a way that you can’t stop fast enough, does it really matter how perfect the car is?”

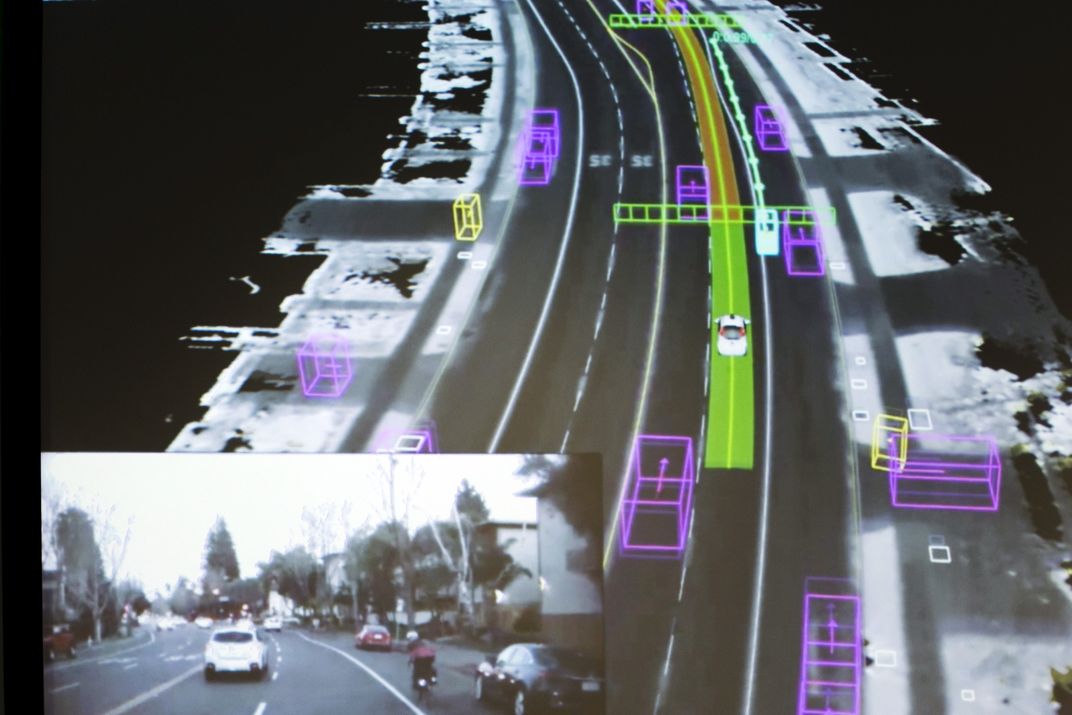

The driverless cars being designed and tested now use a combination of lasers, cameras and radar to navigate roadways and identify objects in or near their paths. Large animals will be relatively easy for autonomous vehicles to dodge. That’s because manufacturers are making avoiding pedestrian collisions a top, nonnegotiable priority. This means the safety of any animal that resembles a pedestrian will benefit under the same umbrella of caution.

“If it looks like a pedestrian, it will be treated like a pedestrian,” says Aaron Steinfeld, a researcher and robotics engineer at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Steinfeld, who has worked on the development of autonomous vehicles since 1998, says sensors now being used on driverless cars pick up information in different ways. Some, for instance, can provide information about an object’s surface—whether it is hard and likely made of metal, glass and steel, or soft and presumably made of fur, clothing and flesh. Any large, soft object will be treated like a pedestrian.

Once the object is identified, the car must decide what to do. Cars that are not fully automated will, in moments of crisis, alert the human occupant and hand over all controls of the vehicle to the human—who, hopefully, will not be busy uploading selfies to Facebook.

On the other hand, the fully automated vehicles that some companies, including Google, are designing, will be programmed to respond to the situation themselves.

To do this in the most agreeable way, Steinfeld explains, the cars will refer to so-called “cost maps”—systems that tell an automated vehicle at any given moment what objects are currently in the vicinity and how costly it would be to collide with them. A pedestrian would probably be associated with the highest costs, as would a semi-truck or any other large vehicle, while a squirrel would probably be identified as relatively low-cost and certainly not worth the risk of swerving to avoid crushing it.

Spotting a moose on the move is one thing. Predicting its next move, however, will probably not be possible.

“This is beyond state of the art,” Coelingh says. “We can only make a rough prediction of the motion of the elk, based on its current position and speed. So when an animal is standing still we need to assume it will keep standing still until we see a movement.”

Andy Alden, a researcher with the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute, says that during a study conducted with Toyota, observations of animals’ actions were a bit too inconclusive to build any predictive capacities into driverless car software.

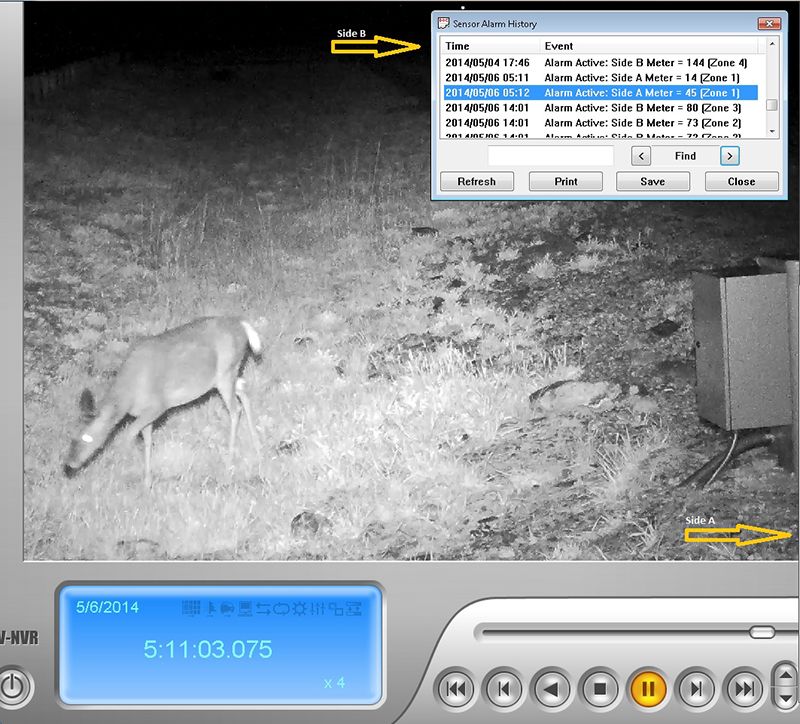

“But there certainly are some things you could drop into an algorithm, like time of day, time of year, the kind of environment along the road, the width of the road, the amount of traffic on it,” he says. “There are lots of parameters that affect your likelihood of encountering an animal on the road.”

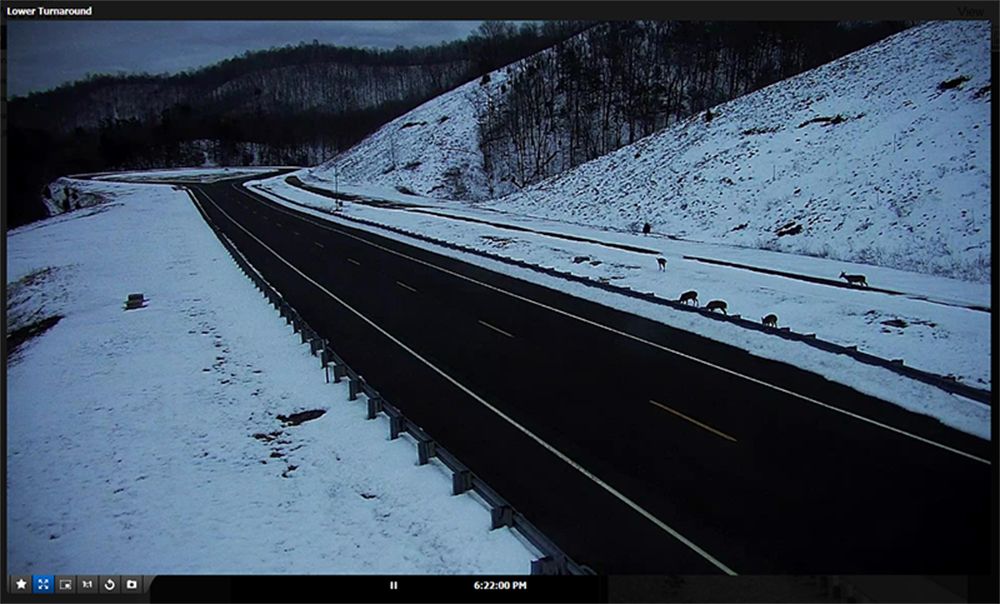

Cars won’t be the only things smarter on America’s future roadways. So will the roads, which in a few places around the country have already been rigged with sensors to inform approaching vehicles of nearby hazards, such as a deer walking toward or on the asphalt. These cables are placed several inches underground and 14 feet from the road, according to Alden. He says the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute has tested one of these lines on an experimental track and found it capable of detecting moving objects as far as 10 feet away. Working in tandem with nearby roadside sensors, such a system could generate alerts for approaching vehicles.

“It would say, ‘You’re on a collision course with a potential problem,’” he says.

In Sweden, smart roads are not currently a focus of research and development, says Coelingh.

“We don’t want to have to add any new requirements to the roads,” he says, adding that information about road hazards, such as wildlife or icy conditions, will be transmitted from vehicle to vehicle via the cloud. “We want these cars to work on the roads that we know today. That way they can be used right away in all markets.”

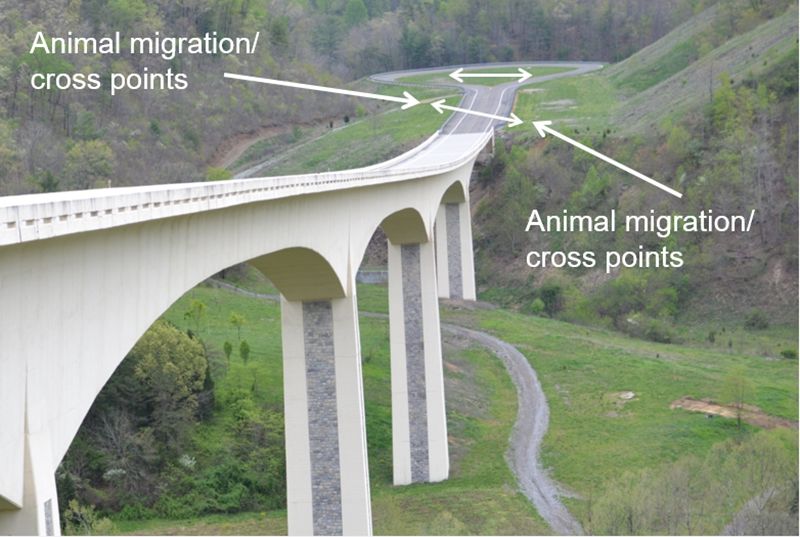

Shilling expects driverless cars will achieve better track records than humans when it comes to driving on roadways crisscrossed by unpredictable wild animals. However, he thinks the best solutions to the problem of roadkill mortality are already available. Fencing along major roadways coupled with green overpasses or tunnels could all but eliminate car-animal collisions in some places, he says.

Cost, he says, does not appear to be the holdup. Billions of dollars, says Shilling, are spent in California alone on roadway work while virtually nothing is spent on keeping animals off of roadways—at least, not while they are still alive. Alden notes that the Virginia Department of Transportation alone spends $2 million per year picking up and disposing of wildlife carcasses.

For any given length of paved, high-speed roadway, placing fencing along each side would amount to a fraction of the cost of building and maintaining that paved surface.

“There are many, many places where it pencils out to build these structures,” Shilling says. “So, I think it is worth investigating the smart vehicle, but it kind of avoids the question of why we aren’t going with the other option of just building the crossings and fencing when it’s so cost effective.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)