Will Microneedle Patches Be the Future of Birth Control?

Researchers are developing a new long-acting, self-administered device that delivers hormones beneath the skin’s surface

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/a5/62a5b60f-5b5b-467c-a311-7d5fde722043/microneedle_birth_control_patch.jpg)

In the seemingly cluttered world of less-than-ideal contraceptive options, researchers are developing one that is more reliable, simpler to use, and looks a lot like a spikey Band-Aid.

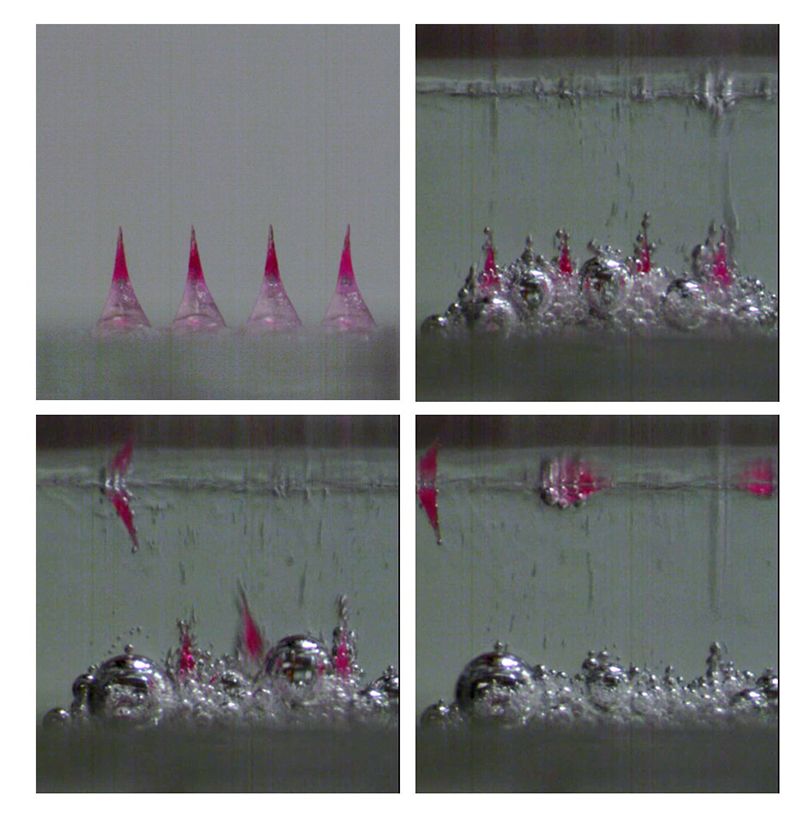

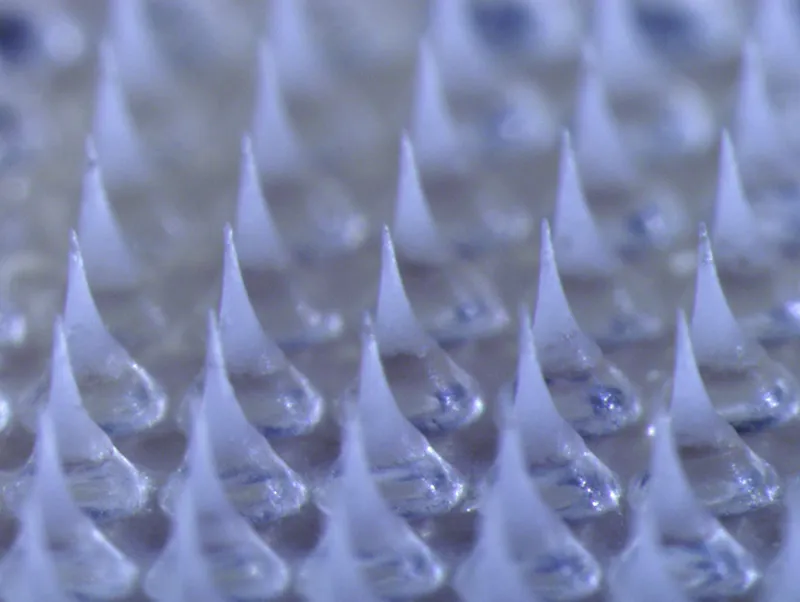

In a study published in Science Advances today, researchers led by Wei Li, a postdoctoral fellow at Georgia Tech, describe a new contraceptive patch with biodegradable microneedles that release hormones under the skin. Building on burgeoning microneedle technology, the needles on this device separate from their backing within a minute and stay embedded beneath the skin, releasing hormones for over a month.

Scientists at Georgia Institute of Technology and the University of Michigan are collaborating on the project, and it is funded by USAID through a grant to the nonprofit humanitarian development organization FHI 360.

The working prototype contains 100 microneedles, which measure hundreds of micrometers in length and are made out of a biodegradable polymer. The user presses the patch into her skin and lets it rest for about a minute. Once inserted, the fluids between her skin cells trigger a reaction in chemical compounds at the base of the microneedles, causing small carbon-dioxide bubbles and water to form. These bubbles weaken the needle’s connection to the backing, and the water further helps the backing to dissolve. This makes it much quicker and easier to remove the backing from the microneedles than is possible in patches without a fizzing mechanism.

Once the microneedles enter the skin, they slowly dissolve, releasing the hormone stored inside into the bloodstream. In animal testing, the hormone concentration remained high enough to be effective for more than 30 days, signaling it may be effective as a long-term contraceptive.

Though the scientists refer to the spikes as “microneedles,” the patch was designed to be painless and the needles undetectable after insertion.

“If we've designed it right, your experience should be that of pressing a patch to the skin,” says Mark Prausnitz, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at Georgia Tech who co-authored the study. “We’ve designed it so that the experience is nothing like a hypodermic needle.”

Microneedling tools are already a trend in cosmetics, used to decrease acne scars and alleviate wrinkles and dark spots. The use of microneedles is also becoming increasingly viable as a way to deliver drugs and pharmaceuticals like insulin and vaccines. Many of these inventions are still undergoing development and testing, and several companies have filed patents for microneedle patches.

These patches are promising because, compared to typical injections, they can be less painful, easier to use and produce no biohazardous waste. Though most other microneedle patches immediately release their drug into the body, the needles in the new contraceptive patch do so slowly over the course of many days. And the new effervescence of the backing allows the needles to break off more quickly, so users must only attach it for about a minute, rather than the 20 minutes some other designs require.

Encased in the microneedles is a dose of levonorgestrel (LNG), the drug most frequently used in intrauterine devices (IUDs) and other forms of contraceptive implants. Though scientists don’t yet know how this delivery method will affect a woman’s body, Prausnitz expects to see similar side effects as other contraceptive devices using LNG.

“We're not innovating in terms of the drug itself,” he says. “We're using a really tried and true drug that's probably been in hundreds of millions of women and has been safe and effective.”

The researchers aim to improve upon existing contraceptives by building one that is long-acting, and easy and painless to apply at home. According to a study published in the journal The Lancet last year, 44 percent of pregnancies worldwide between 2010 and 2014 were unintended. By providing another reliable and accessible contraceptive option, researchers hope to help reduce this number.

“Even with all the choices that exist today, [contraceptives] are not doing what's needed for everybody,” Prausnitz says. “What motivates us is that if we can figure out the science, there can be some good that comes of it.”

The team has so far tested the hormone delivery on rats and a placebo patch on human subjects. The researchers have also conducted interviews and surveys with women of reproductive age in the U.S., India and Nigeria and found the patch was well-received conceptually by these women and physically by the test subjects. Only 10 percent of the subjects who tested the placebo patches reported feeling pain initially, and none were in pain after an hour. None exhibited tenderness or swelling, though some still experienced redness of the skin after a full day.

“Alternative approaches to delivering contraceptives beyond the once-a-day oral pill stand to transform the user experience and maximize patient adherence,” Giovanni Traverso, a gastroenterologist and professor in MIT’s department of mechanical engineering, writes in an email. Traverso, who was not involved in the research, has developed a pill that, after being swallowed, opens in a person’s small intestine, allowing microneedles inside to inject drugs into the bloodstream. “As a community we are enthusiastic about the potential of microneedle patches for extended release of a broad range of drugs, but certainly the impact for contraception is significant.”

The device likely won’t be ready for clinical trial for another two to three years, and it would be several more years until it could be FDA approved and marketable. In that time, researchers will be increasing the quantity of LNG carried in the rat-sized patches tenfold to make them usable in humans. Their challenge is to increase the capacity of the needles without making them too large and painful.

Another crucial next step is to prolong the length of the hormone release. Ideally, they will be able to create a patch that can be changed every three and six months, rather than just one. Reducing the number of patches women have to buy could significantly decrease the overall expense.

“USAID certainly has the mission to bring this kind of patch to developing countries and making it accessible, which means the cost has to be right,” Prausnitz says. “They've made it very clear to us that the target needs to be that a patch must be competitive with the cost of other contraceptive methods.”

If they succeed, scientists may be able to create a product that gives women around the world a much-needed new contraceptive option.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_1578_copy_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_1578_copy_copy.jpg)