Will Skyscrapers of the Future Be Built From Wood?

Why cross-laminated timber might become the newest trend in urban architecture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/24/b7/24b7beff-8792-4393-bd16-ed6c5934b8f6/empire-state-of-wood.jpg)

New York City is home to some of the most famous skyscrapers in the world, from the Chrysler Building to the Empire State Building—structures of concrete and steel that, when built, seemed to defy both the bounds of human innovation and the laws of physics. But visitors to New York City’s West Chelsea neighborhood might have another surprising building to admire in a few years—a ten-story residential high-rise built from wood.

When completed, the building—the brainchild of New York-based SHoP Architects—will be the tallest building in the city to use structural timber to hold up its 10-story frame. But, if the timber industry, the United States Department of Agriculture, and a growing cadre of environmentally conscious architects and designers get their way, it will be far from the last—or the tallest—wooden structure to grace an American city’s skyline.

In September, the USDA, in partnership with two timber industry trade groups, awarded $3 million dollars to two projects that the department hopes will catalyze tall wood buildings in the United States. The two projects—the 10-story building in New York and another 12-story building in Portland, Oregon—are perhaps the most significant examples of a concerted push, championed by both government and private industry, to make cross-laminated timber, or panels of timber made from adhering pieces of smaller wood together, the building material of urban America’s future. Those involved with the projects, like Portland architect Thomas Robinson, say that the competition will hopefully help impact change in the United States building code, which currently doesn’t allow for high-rise timber buildings. There is a provision in most cities’ building codes, however, that allows for tall buildings to be made of wood if the builder can prove that the tall wood building performs as well as the standard. Much of the prize money, at least for the Portland building, will go towards testing to prove that a tall wood building is just as safe—in the event of earthquakes or fires—as a traditional steel and concrete building.

“One of our biggest goals is to make working with cross-laminated timber another choice for architects and developers,” Robinson says. “Right now it’s not an easy choice to make, you have to want to do it.”

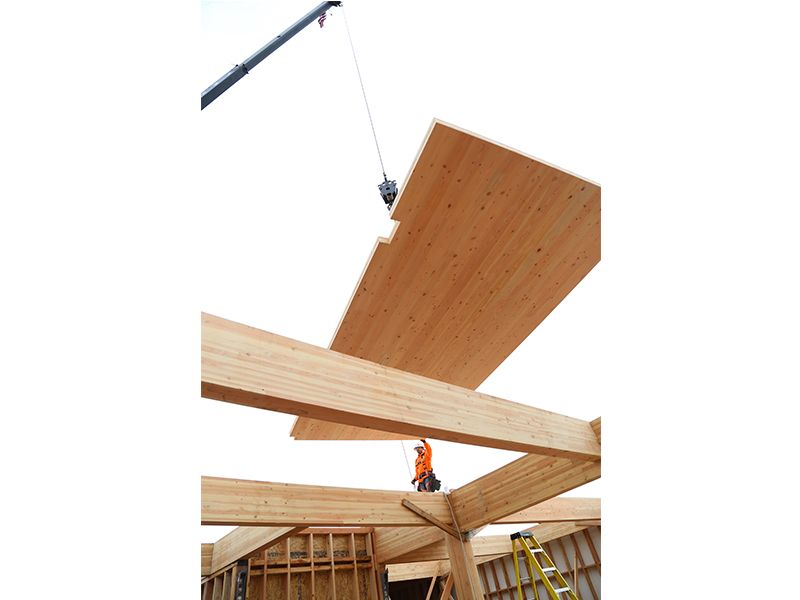

Creating tall wood buildings is an inherently different process than building a house with two-by-fours. Tall wood buildings use mass timber products, which are large wood panels engineered for strength by adhering smaller wood pieces together. A single panel can be as long as 64 feet, as wide as eight feet, and as thick as 16 inches. Builders use these timber products for the main structural frame, and then rely on concrete and steel only at locations in the building of high stress, like joints. Mass timber products can be pre-assembled, almost like huge Lego pieces, so building with them can be cheaper and more efficient.

Wood as a building material is not, in and of itself, a revolutionary concept: builders have used wood for millennia, building everything from log cabins to magnificent temples. But wood has never been the material of choice for skyscrapers, which trace their history back to the tail end of the Industrial Revolution, when the mass-production of material like steel was becoming relatively cheap and widespread. The first building to be called a “skyscraper” was the Chicago Home Insurance Building. The 10-story building was also, in 1885, the first building in the world to use structural steel in its frame. Nearly two decades later, architects revealed the first reinforced-concrete skyscraper, the Ingalls Building in Cincinnati. And so began a veritable arms race between architects, with their steel and concrete, jockeying to produce the world’s tallest building.

Michael Green, an architect based in Vancouver, British Columbia, is no stranger to tall, steel-and-concrete buildings. He spent the majority of his early career working on some of the most famous skyscrapers in the world, including the Petronas Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur, which, at 1,483 feet, were the tallest buildings in the world from 1998 to 2004.

When Green moved back to Vancouver, however, he eschewed the concrete and steel of his early work for his preferred building material: wood. But for Green, the choice was about more than just aesthetics. Currently, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities—but that number is expected to increase to 66 percent by 2050. Green understood that more people moving into cities meant there would be a demand for bigger buildings. According to the United Nations, some 3 billion people, or 40 percent of the world’s population, will require access to housing by 2030. And the architect just couldn’t seem to reconcile that demand with the environmental impact of traditional materials used for skyscrapers—the carbon intensive, nonrenewable steel and concrete.

“Steel and concrete don’t grow back. They are not renewable materials,” Green says. “They are not even remotely renewable materials—they use massive amounts of energy in their creation, whereas the most perfect solar power system of making any material on Earth is the making of our forests.”

But beyond being a more renewable building material, United States Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack and other proponents of tall wood buildings believe that creating taller structures out of wood could help the world fight climate change in another way, by ensuring that forests, which can act as carbon sinks by storing and sequestering carbon, don’t become carbon sources due to forest fires.

“Broadly, we are concerned about the fact that there are an extraordinary number of diseased and dead trees in the western United States that represent a severe fire hazard,” Vilsack says. “In order for that wood to remain a store of carbon, we’ve got to figure out a way to use it, otherwise Mother Nature will ignite a forest fire with a lightning strike, and we will lose the carbon that is stored in those trees.”

In the United States, millions of trees are diseased and dead, due in large part to climate-driven problems, such as pests and drought. In California alone, just last year, some 29 million trees died due to a drought-driven bark beetle infestation.

Vilsack says that it was these dead trees, in large part, which inspired the USDA’s interest in tall wood buildings. If done responsibly, he explains, removing these dead or diseased trees, to be used for making cross-laminated timber that would eventually support tall wood buildings, could be a win-win for both the timber industry and environmentalists—two groups that traditionally have a contentious relationship.

“We’re confronted with an intersection of interests, in which those who are concerned with conservation and the environment think, ‘My god, we can’t continue to have millions of trees,’ and those who are concerned about the logging and timber industry think, ‘My god, we’ve got to be able to figure out what to do with these dead trees so that they don’t just create horrific fire hazards,’” he says. “This is the right time, if we do it in a collaborative and thoughtful way.”

But tall wood buildings are far from an architectural certainty. Green says that the building community seems to just now be coming around to the idea of using materials other than steel and concrete for large projects.

“Once people started getting their heads around the idea of there might be a carbon reason, then it jumps to other things. Is there enough wood in the world? Is it going to be safe? Is it going to burn down?” Green says.

Proponents of tall wood buildings argue that they are no more fire-prone or dangerous than traditional skyscrapers, and Green says that part of his work nowadays consists of educating the public—clients, engineers, and other architects—about the benefits of building with wood. The message seems to be spreading—in the last five years, 17 buildings over seven-stories tall have been constructed using wood, from Sydney, Australia to Canada. Green is working with a developer in Paris that said that they cannot stop the flood of desire for buildings built in wood. In Vancouver, developers are working on a 1-million square foot project (that’s roughly the size of Washington, D.C.’s Reagan National Airport) made entirely of wood.

It’s this wave of tall wood buildings popping up around the world that Green believes will inspire architects and builders to push the bounds of how high a wood building can go.

“It’s how the history of building worked,” Green says. “When the Chrysler Building was being built in New York City, the developers of the Empire State Building said that we need to be taller, we need to be bigger.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)